My post-Cambridge blues

Columnist Jess Lock reflects on life after graduation

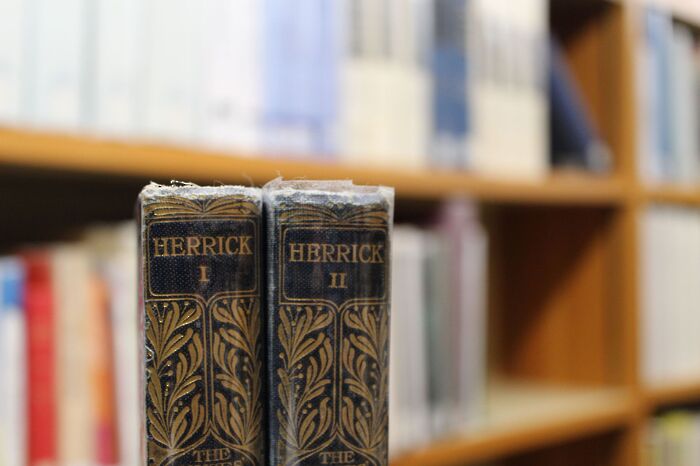

My body clock is on autopilot. As the evenings get a little shorter, and the mornings a little cooler, I feel the urge to start packing up my things. My yearly migration back to Cambridge is hanging in the air. At least, that’s what the past three years have ingrained into my circadian rhythm. But this time around, I won’t be returning to the red brick of Newnham or the portered doors of Kings, and I won’t be lugging hordes of books back to the libraries either.

It’s only been four months since I’ve graduated, but already my memory of this place has begun to warp as I nostalgically reminisce about punting, chatting with friends down the corridor and cooking with them, celebrating special occasions at glorious formals, hanging out in beautiful gardens, and basking in post-exam joy. My gut isn’t twisting at the ferocity of the reading list, or the longing for my family — sensations I logically know to have punctuated my termly returns. For the first time since beginning Cambridge, I actually want to go back. What a horrible feeling!

What I want, I cannot have, and like a spoilt child, I feel like throwing a very loud tantrum about this.

My days now consist of something different. I’ve got a job in London, a lovely shared flat, and enough money to eat healthily and still afford the train back to my supportive, welcoming family. I’m fortunate, and I do feel it.

I ostensibly have nothing to mourn. And yet, like so many grads I’ve spoken to, I feel an unutterable sense of misery. The veneer of an attractive career and the line “I’ve made the move to London,” which is so often reciprocated with cooing congratulations, hides a devastating sense of loss that rumbles deep in the pit of my stomach. If I complain, I feel bitterly ungrateful, so instead self-censor in embarrassed guilt. But when I’m not complaining, I find myself sitting on the tube wondering whether it’s possible to silently dissolve into the rush hour hubbub, leaving behind a neat stack of clothes on the grubby seat.

The identity I’d curated around academic success (and moreover, an earnest love for the things I’d learnt) has been quickly, quietly dismantled into sharp suits, a nine-to-six job, and a polite telephone manner.

I’m suffering from a severe case of the graduate blues. It seems laughable, something I myself can’t help but cringe at, fully prepped to weather sneers that accompany such first world problems. But leaving full-time education for the first time in 17 years has disoriented me more than any careers guide, workshop, or graduation talk could ever have prepared me for.

I feel isolated, gutted and directionless. I feel guilty and infantile for these feelings.

Perhaps I ought to have anticipated the destabilising shift from short university terms and their days punctuated by naps and endless natter, to daily commutes and pension schemes. I knew both my sleep schedule and my student finances would take a sucker punch when I entered ‘the real world’, but I didn’t preempt the sharp decline in social interaction. I didn’t expect the big city to be quite so faceless, for phone calls with friends to feel quite so perfunctory, or for my most meaningful interaction in the day to be collecting my bulk-bought toilet roll from the concierge in the apartment complex.

Gone are the boundless hours of lounging on friends’ floors commiserating on our cruel supervisors and regrettable life choices. And gone is the sense that my time is my own. In my lunch break and the snatches of time I find between waking up before work and going to sleep after it, I feel myself trying to claw each second out into the longest shred of time it can be.

I expected grad life to deliver structure, and with it, purpose and meaning. I’ve found instead that I’m gasping for the breathing space that my time at Cambridge had allowed me.

I feel isolated, gutted and directionless. I feel guilty and infantile for these feelings. I feel like I’m making a fuss out of nothing. I feel like I’m coping and then I feel like I’m not coping very well at all. I feel like I can’t burden my parents or my friends with these thoughts, thoughts I can’t seem to unpick myself. I feel like what we're told about life after graduating doesn't match up with reality, and needs to be established.

And so the dialogue is opened. Fleetingly, perhaps, and diminutively too, but articulated nonetheless. Though I may feel lonely, I know I’m not alone.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025