Learning to critique helped me critique my learning

Cait Findlay writes of her journey of academic discovery, from Shakespeare to queer theory

I began this series of columns last year by describing it as the non-academic lessons that I’ve learned at Cambridge, outside libraries and supervision rooms. However, it would be unrepresentative to neglect the non-academic lessons that I’ve learned in specifically academic spaces, alongside the quotations and critical debates that I’ve spent the last three years considering.

Thanks to Cambridge’s exam-based assessment style, I’ve crammed a lot of information into my brain in the last few months about such diffuse topics as Aristotle’s position on tragic theatre, the role of architecture in shaping experiences in museums, and medieval beliefs about ghosts and magic. Such is the beauty of an English degree. Most importantly, I’ve learned that following your interests does not make you a cliché — it makes you a better student.

I’ve often been worried about somehow being boring or not ‘academic’ enough by choosing to write about things that I have a personal interest in. I don’t want my identity to become my only point of interest academically. I don’t want to write about women or queerness purely because I am a woman and queer. For instance, at school, whenever a question about women and feminism came up in English lessons, a groan would go up around the room and all eyes would swivel towards me.

It became a bit embarrassing, something I would get defensive about — and when I came to Cambridge, I was deeply concerned that writing about queer theory, feminism, certain authors, whatever it may be, would somehow diminish my academic credentials and raise supervisors’ eyebrows. However, I found the opposite to be true; students and supervisors here tend to be more accepting of personal intellectual interests, with the notable exception of one who said we should ‘forgive’ Spenser for being a misogynist because he was a reflection of his times. Yes — and a feminist reading is a valid modern critique.

Whenever a question about women and feminism came up in English lessons, all eyes would swivel towards me

By the time I got to third year, though, I changed my position. I realised that there is no more academic credit to writing about structuralism or post-structuralism (and to be honest, I still don’t entirely know the difference) than there is to writing about queer theory or intersectional feminism.

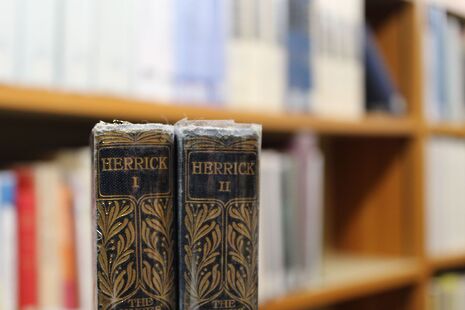

Shakespeare may form a large part of the English Tripos, but that’s not to say you can’t find anything more interesting to write about in Aphra Behn or Margaret Cavendish. In fact, certain writers and areas have been under-researched, and are therefore extremely exciting areas to look into. This is a very English-centric view, because it’s obviously the subject I know best, but it translates across into other humanities subjects, too.

The essays I’ve written on issues that I’ve had a personal connection to have often been my best essays, at least in terms of enjoyment. For my second year portfolio, I wrote about romantic friendships as covers for lesbian relationships in a novel and Anne Lister’s diary, and it was certainly one of the most fun essays that I spent time reading and researching for, even if I never got to hear back about precisely what mark it got. The library hours flew by far faster than when I had to read four of Shakespeare’s history plays in a week.

My second year dissertation was about the capitalism and the female grotesque in Margaret Atwood’s novels, making the argument that intense scrutiny on women’s bodies is intended to maximise their spending on beauty products, but that the standards of beauty are eternally changing, which means that consumerism thrives eternal. Writing about those topics was a better use of my time and energy that forcing myself to cover the same dry content that has been done by so many before me.

I have emerged from the other side of my three years at Cambridge with a vastly improved knowledge of the literary canon (although it is still limited to a very Western-centric vision), but the educational byproducts of my studies and other opportunities I’ve had have been just as important to me as my degree itself. Sports, student politics, and social endeavours have taught me various lessons: that showing up for other people builds mutual bonds of love and support; that looking after your mental wellbeing looks different for everyone; and that leaving your room will lead to either a good time or a good story.

The prospectus sells Cambridge as a package, and it truly is. On one hand you get the academic challenge that makes it the best university in the UK. On the other, you learn a whole host of things that you never expected.

Thanks, Cambridge.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025