Rafiki: dismantling the myth of an ‘un-African’ queer love

Waithera Sebatindira reflects on holding the screening of Kenyan film, Rafiki

Rafiki is not the first queer love story to be told on the African continent, nor will it be the last. The film follows two young women living in Nairobi, daughters of rival politicians, who expose deep-seated political rifts and the dangers of widespread homophobia when they fall in love. It’s a moving love story drawn together by young but seasoned director Wanuri Kahiu and, refreshingly, it lacks the voyeurism so often found in movies about women in love, which are usually directed by men. Beyond that, Rafiki is significant for me because it adds a new dimension to my understanding of my queer self. Coming out in Cambridge was made easier for me by a community of queer black women, but the images of queer love I saw there were still overwhelmingly white, and inevitably British. This film ties to me to a community in Kenya that I’ve yet to fully engage with, but that I know is waiting for me when I return home.

The themes in Rafiki have been examined by other African storytellers. From Monica Arac de Nyeko in Uganda, whose short story inspired Rafiki, to Nigeria’s Wole Soyinka and Tendai Huchu in Zimbabwe among many others. So why decide to organise a panel event about Rafiki in particular, and why in Cambridge?

"This film ties to me to a community in Kenya that I’ve yet to fully engage with, but that I know is waiting for me when I return home"

Beyond my personal connection to the film’s setting, the political response to its release threw up a lot of pressing questions for me – questions I felt could be answered well if I had access to the University’s resources. Having devoted time to building relationships with professors in the Sociology and African Studies departments during my time at CUSU, I chose to ask for their help in organising an event unlike any I’d ever seen take place at Cambridge.

Upon its release, Rafiki was immediately banned by the Kenya Film Classification Board for “promoting lesbianism” and posing a threat to Kenyan values (the Supreme Court has since struck down the ban). It struck me that I’ve been hearing similar rhetoric while studying in England, where immigrants and their allies are regularly deemed threats to “British values”. I asked of my own country the same questions I ask while I’m here. What are these so-called values? Who lays them down? Are LGBT+ Kenyans incapable by virtue of their very existence of upholding Kenyan values? Are they Kenyan at all?

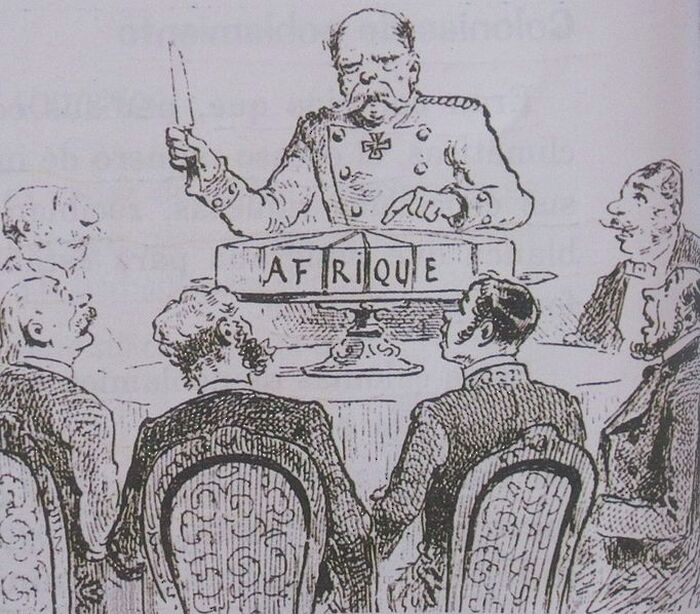

The question has been asked in various contexts before, but I wanted to look specifically at what it means for an African country to reject an entire group of people as part and parcel of its process of postcolonial nation-building. Most of the rhetoric in which African homophobia is rooted insists that homosexuality is somehow “un-African” – a Western import. The primary weapon I see used against this myth is the excavation of evidence that same-sex sexual behaviours and ritualised practises existed long before Europeans unleashed their tyranny (and their culture) on to our continent.

"I love the idea of existing as a hybrid; someone who is not totally the product of her culture’s pre-colonial past but who has also not assimilated fully into the culture of her former colonial masters"

This is important work and I feel validated by it. I love the idea of existing as a hybrid; someone who is not totally the product of her culture’s pre-colonial past but who has also not assimilated fully into the culture of her former colonial masters. My identity as a queer woman is made richer when I combine the queer semiotics I’ve acquired by being in England with a history of non-normative sexualities within my Kikuyu tribe that have nothing to do with Western influence. But more needs to be done (and is being done) because myths such as these do not propagate purely because of ignorance. Lies about minority groups persist because they uphold structures of power.

I wanted to organise an event that would examine exactly what these structures are in country-specific contexts on the continent, what work is being done by grassroots activists to achieve sexual justice, and would explore the ways in which LGBT+ politics can be used to ensure that the process of nation-building, or (after we inevitably abolish our borders) community-building, on the continent is a truly decolonial project.

The lgbtq@Cam programme has invited three incredible panellists to tackle these very questions at a screening that has been co-sponsored by the university’s African Studies department. In chairing the panel I hope to come away from the evening with a set of new tools. A greater understanding of the inherent contradictions involved in building an anti-colonial nation state. A stronger capacity for solidarity across nations within the continent; the chance to learn about the different ways that LGBT+ Africans define themselves and their experiences. Another weapon against patriarchy as I can better articulate the ways in which feminist and sexual justice goals are inextricably tied. And hope for an African future in which the politics that has emerged within communities of sexual minorities is championed in the decolonial struggle and, in the process, used to create new communities that recognise the creative function of difference in our lives. In short, my primary reasons for helping to organise this event are selfish: I want to understand myself better and see where myself and my politics fit within the political climate in Kenya and other African countries. If other people can take something similar away, too, that’s an added bonus.

Rafiki will be screened at the Bateman Auditorium at Gonville & Caius College on Wednesday 28thNovember. The screening will be followed by a reception and panel event

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026

Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026 Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026 Theatre / The ETG’s Comedy of Errors is flawless21 January 2026

Theatre / The ETG’s Comedy of Errors is flawless21 January 2026 News / Write for Varsity this Lent16 January 2026

News / Write for Varsity this Lent16 January 2026