Who gets to tell Africa’s narrative?

This week, columnist Daniella Adeluwoye explores how a Eurocentric view of Africa has coloured her relationship with her African heritage.

'Dad, some girls in the playground said my relatives ride animals in Nigeria,' I said in between tears. I’m met with silence at the dinner table.

'It matters who tells our story, Daniella,' he whispered in response.

Whenever African history was discussed in the classroom, a feeling of shame and humiliation would well up inside of me. ‘Backwards,’ ‘primitive’ and ‘hopeless’ were adjectives that dominated the prevalent narrative. I grew frustrated because I just didn’t understand why my heritage was labelled as inferior.

To my younger self: I understand the frustration you feel

Considering that our culture honours schools as institutions where education is taught objectively, it didn’t make sense to me as to why these misrepresentations of Africa were being perpetuated. As I’ve grown older, I’ve realised that the crucial question we should have been asking is whether this ‘neutrality’ towards Africa’s narrative is objectively tenable in the world we live in today. Why is the rich history of the Benin Empire filtered out and instead we are taught about how colonialism wasn’t inherently evil? I’ll answer that one for you: for heaven’s sake child, they gave us the railway system, be grateful!

Did we ever engage with the fact that knowledge is always imbricated with power? No. Did we learn how our perspectives are influenced by our geopolitical positioning which circumscribe how we narrate? Of course not. The dominant narrative around Africa has focused on depicting the continent as ‘underdeveloped’ whilst conveniently juxtaposing this image against the beacon of hope that Western civilisation provides, the beacon of hope that Britain itself is deemed to represent.

The dominant narrative around Africa has focused on depicting the continent as ‘underdeveloped’ whilst juxtaposing this image against the beacon of hope that Western civilisation provides

The labels ascribed to my culture confused my younger self. My African identity was something I was taught at home to be proud of. But as soon as I stepped outside, society said otherwise.

In retrospect, I would have been delighted to know that I could criticise the premise of the word ‘civilisation.’ I didn’t have to accept the narrative that Africa was 'underdeveloped'. Africa was never meant to conform to a Eurocentric metric of progress. Instead, it should have been allowed to formulate its own criteria of ‘development’ that suited its people. Civilisation is a relational term and thus it only makes sense when you have alternative outlooks with which you can contrast it. Implicated in the word ‘civilisation’ is the notion that Africa deviates further from the universalisation of free market capitalism and neoliberalism, temporally marking the continent as ‘uncivilised’. It is this rhetoric of civilisation that has historically perpetuated the colonial encounter and Africa’s portrayal as the ‘Dark Continent.’ It is this rhetoric that has contributed to an unconscionable feeling of shame in my own understanding of my own heritage. My heritage was not something to be proud of, but to be pitied by the girls in the playground.

Civilisation is a relational term and thus it only makes sense when you have alternative outlooks with which you can contrast it.

Geography classes further contributed to my confusion: I would only get the mark if I labelled Nigeria as an example of a ‘least developed country.’ What the education system did manage to do was conceal the cracks of Africa’s exploitation by the West. So, stop telling me how Africa’s ‘lack of development’ is its own fault. The idea that Africa suffers from a lack of development is flawed because it suggests there is a teleological direction that all societies must aim towards. And, you guessed it, the finish line is the West’s ‘universally’ applicable model of development.

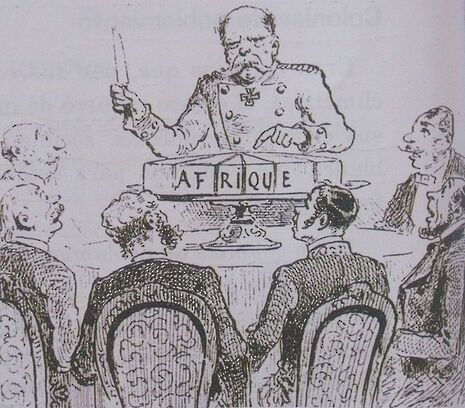

In retrospect, it was telling to uncover the long-term detrimental effects that the Berlin Conference had on Europe’s colonial history and their own cultural consciousness. Writing this column, it upsets me that British society taught my younger self to be ashamed of Africa’s current position when I now know that it is not Africa’s shame that I carry, but rather it is white Britain’s unprocessed colonial guilt forced onto me, a person of African heritage, to carry.

But please don’t sit too comfortably, I must remind you that this epoch is not as historical as you may think. In a society which has failed to come to terms with its colonial past, I have spent much of my time searching through endless tabs on my browser to explore the backdrop of Western imperialism. The fact that those political and economic parameters through which the West operated during the transatlantic slave trade are still maintained today, in the form of neo-colonialism, is often overlooked. What I have realised is that it’s an identical narrative to the one that the world witnessed in the previous century. It’s just subtler, so you don’t notice. After the Cold War, many countries in Africa were reduced to crises-ridden nations. Structural Adjustment Programmes were used by the US to secure Africa’s ‘stabilisation’ whilst they extracted their natural resources. So, don’t tell me how this veneer of international humanitarian intervention is not as violent as it used to be. If anything, the subtleness of the West’s interests in our modern age poses consequences that are just as dangerous as the ones in our history textbooks. I always wonder what, if we were more conscious of the West’s empty rhetoric and ulterior motives, Africa’s narrative would be today?

I now know that it is not Africa’s shame that I carry, but it is rather white Britain’s unprocessed colonial guilt forced onto me, a person of African heritage, to carry.

To my younger self: I understand the frustration you feel. I am sorry that you had to feel that way, it is not something that you need to carry. Growing up as a young girl of Nigerian heritage, you were never given any reason by the education system or the country you live in to be proud of your heritage. It upsets me that it is only writing this now, 10 years later, that I have begun to understand why you weren’t always proud of your identity.

You will soon grow to your love heritage. You’ll accept that your hair won’t ever fall, and nor will it look good with a fringe. So, go ahead, unfollow the Instagram models on your feed who conform to Eurocentric standards of beauty and follow women who look more like you. You will discover the beauty of Africa’s writers, its historical and political figures. You will get to tell Africa’s true narrative. You will get to tell your own narrative.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026

News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025