‘It explains so much’: finding liberation in a diagnosis

Ferdy Holley found the answers to life-long problems when he was diagnosed with dyspraxia and ADHD

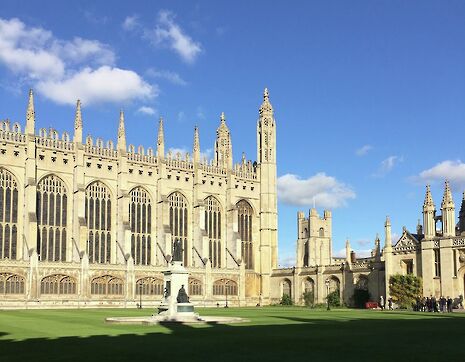

Results day 2018. After finally remembering whether CamSIS or CamCORS is the one with the results on it, I located my long-dreaded exam results. Trying desperately to block out memories of the land law exam where I might as well have handed in a lump of turf instead of the exam script, I opened my results and, eyes squinted, peered at them. My stomach rapidly shrivelled up into that familiar nauseous feeling of shame which had been lurking there on and off since this time last year. It was, indeed, a 2:2.

As my other friends revealed their more vindicating results, 1sts and 2:1s, I tried to conceal my rising sense of unworthiness and embarrassment. It was tiring, feeling so inadequate.

It never occurred to me that they could be symptoms of something more than just laziness or incompetence

This was not the first time I had felt this way. Although I did well in my GCSEs, A Levels were a challenge and I missed my offer, only scraping my way into Cambridge after several hours of tense phone calls. First year, I emerged with as low as a 2:1 as you can get, underperforming every other lawyer at my college. It seemed that every year I did worse relative to those around me, and this latest result seemed only more confirmation that I was on a downward spiral.

I knew the cause. As time had gone on it had become clearer that there was something seriously wrong with my studying, chiefly that I wasn’t doing any. Essays were left to the last minute. Revision went undone. Exams were hazarded on horrific all-night cramming sessions.

The diagnosis was liberating, validating

It wasn’t for lack of will. The main problem was an inability to concentrate. In Law, the lion’s share of the reading comes in the form of 70-100 pages of the sort of textbook which I fear putting on high shelves lest I be crushed to death. Nobody’s idea of a page-turner. But still, I love my subject and find it fascinating and you would think, therefore, that I could at least claw my way through a half hour session. Not so.

Scarcely more than 10 minutes in, my brain seems desperate to escape, to distract itself, to find any other thing to think about or focus on other than the page in front of me. I would find myself wandering around aimlessly, or doodling idly in a notebook, or flicking my glazed eyes over the same 6 entries on Crushbridge for the 12th time.

The formless barriers which had been plaguing my mind for years now had a shape

Even having recognised this problem, it never occurred to me that they could be symptoms of something more than just laziness or incompetence. When discussing it with my family, the response was a monotony of polite scepticism. “You just need to take it a day at a time” they would say. “You need to be more positive”. For a long time, I was led to think that all that was needed for an instant reversal of my fortunes was a brisk attitude and a set of those Stabilo pens. And then, one day in second year, a conversation with a friend about ADHD sparked something in my head. So I went to see my GP.

The doctor referred me to the Cambridge Disability Resource Centre, where I went for an hour of tests and questions about my difficulties. They then referred me on to a diagnostic assessor in London where I went for another 4 hours of tests and questions with the result that, at long last, I was diagnosed with dyspraxia and ADHD.

The diagnosis was liberating, validating. It is now a cliché but it really did explain so much. The formless barriers which had been plaguing my mind for years now had a shape. I knew I would be able to get more support - extra time in exams and access to a word processor, plus other assistive software for my studies.

It explained other things as well. As a child, I had been strangely reluctant to learn anything involving motor skills. Tying shoelaces, riding a bike, swinging myself on the swings. As a child, I was adamant that I had principled, sensible reasons for this reticence. I mean, who on earth, when looking at a tricycle, thought it would be much improved by having only two wheels in a straight line which you had to balance precariously on? It was madness, childhood me thought. Looking back, though, there was clearly more going on under the surface. The fact was that I struggled with these tasks. I just couldn’t get my hands and feet to do the things they were meant to. Now, a decade and a half later, I had myself an explanation: dyspraxia.

To anyone who has found themselves faced with similar symptoms, please go and get them checked out. You have almost nothing to lose and a lot to gain. For me it was a totally chance venture, the tying up of a potential loose end. But it ended up being the best possible outcome for me. The day of my diagnosis was something I hadn’t had in a long while - a results day I could feel happy about. And what a wonderful feeling that was.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026