‘I love to laugh about everything that my dad was’

In her final column, Ana Ovey explores the importance of retaining the simple memories in grief

In writing the last of these columns on coping with grief, there is an overshadowing urge to do justice to the memory of my father. Retention has been one of the most important, and easily shaken, aspects of my grief. I want to remember the sound of my dad’s voice, what he’d say when I got home from school, what his favourite songs were, how loudly he’d laugh at my jokes. The ferocity with which I’ve attempted to hold on to this has often been painful: what has caused the pain is the acknowledgement that I cannot possibly remember everything that my dad was. This scares me because it means acknowledging that though I know I miss him, and that his loss hurts, he’ll still be gone, and I can’t render him living in the inevitable imperfection of my memory.

But it’s still vitally important, certainly to me, to remember. I love to laugh about everything that my dad was. I love, in a strange way, to cry about it. I love knowing that he meant so much to his wife, to his sons, to his friends, and to me. The most precious things people said to me following my dad’s death were memories. I adored talk of mischief he caused, of university friends sharing silly little anecdotes, of colleagues laughing at games or pranks my dad took part in. I loved his students telling me what they’d learnt from him and how he’d taught it in the most ridiculous way. I loved his friends telling me about things he’d said to them, whether these were wise, funny, outrageous, or caught anywhere in the middle.

“It was at a new meeting point between heartwarming and heartbreaking”

After my first column, people in and outside of college messaged me lots of kind and encouraging things — but one message was particularly touching, and particularly identifiable, from someone who had also lost their dad. It was what prompted me into thinking, a little more deeply, about what the importance of memory to someone grieving. ‘I find I often just want to talk about how cool my dad was,’ was the message that contained a sentiment so recognisable to me, as was what followed it: that people tensed up, whenever she tried.

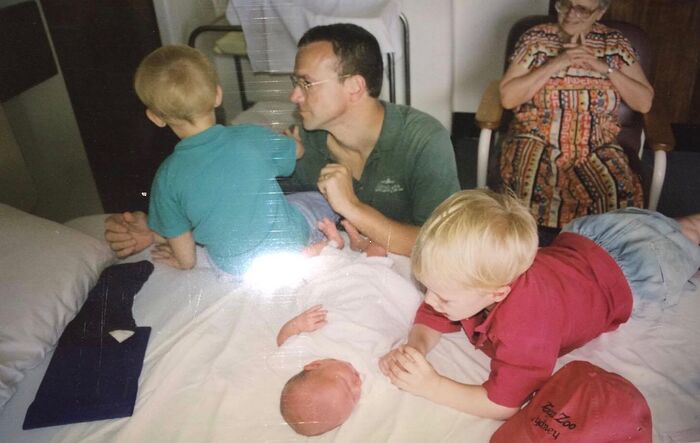

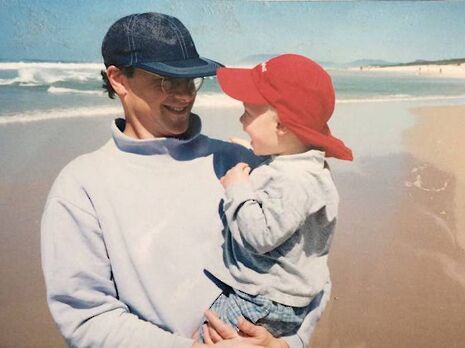

I went back out to Australia at the end of February, apprehensive about how it would be to be in mourning and in another country, on the other side of the planet, on my gap year. But something that helped me enormously, along with all the support and love I was being shown in Sydney, was the love I was being shown back home, in the form of various video calls from my brothers, my mum, and my close friends. One call I got from my oldest brother was one of the loveliest, and most bittersweet, I can remember. He’d been looking through old photographs of our family, and recalling all the memories they held. I watched, over ten thousand miles away, beaming and trying not to cry, as he showed photographs and told me about them. He shared his memories, and we both shared love for our dad – and how much we missed him. It was at a new meeting point between heartwarming and heartbreaking that other griefsters will be familiar with. I was so grateful. Laughing tearily as your brother tells you the story behind the photograph of him and your dad on the beach is an unexpectedly precious thing.

“The past is something to be engaged with”

During a week of Michaelmas that was particularly messy, I was invited to the house of some family friends who’d just moved into Cambridge. Aside from having enough lovely children to distract anyone from the retrospect of a rubbish essay and a disheartening week, they were also able to share with me recollections of a father I sorely missed, and desperately wanted to talk about. It wasn’t that I wanted to cry about him – although I did – I wanted someone who knew the person I had lost, and was able to share memories of him. The moment that prompted a giggling recollection was someone entering a coughing fit after laughing a little too hard, which had been a notoriously characteristic trait of my dad’s. As it happened, I beamed – so did one of the family friends, and I was able to share a momentary laugh about what had been one of my dad’s most ridiculous, and easily satirised traits. It was something tiny, but it meant so much, after a week that had been so hard and lonely.

Memory is important, because it’s personal. I navigate life more retrospectively than I did before my dad died, and so much of what he did and taught me offers me guidance in my new context. I’m also reminded, with joy and heartache, the running jokes he made, the songs he loved, the embarrassing things he did. Sharing memories like this is important. The past is something to be engaged with – for the person communicating it, and the person listening. And, if you have lost someone, you’ll never be able to remember the number of hairs on their head, or the precise angle of their smile, or the first thing they said to you on your seventh birthday. You will remember odd and heartwarming anecdotes: the worst meal they cooked for you, the awkward way they offered high-fives, how strong they liked their coffee. And these things, however seemingly banal, are precious – because the person you grieve for was precious. Hold on to that

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025