In grief, the truth can be something that we hide from

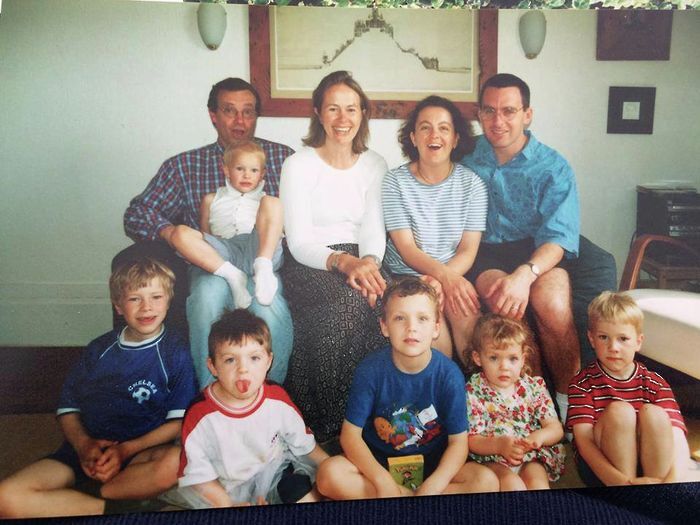

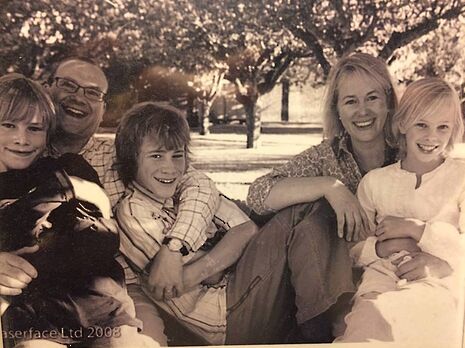

“The human mind is a mind of associations… the truth is that not all those associations will be good”: columnist Ana Ovey on grief’s everyday triggers

One of the things often neglected in talk of grief is that the inexplicable and mundane can often set it off. This is something I’ve struggled to articulate to people who haven’t known it, but equally something I fail to acknowledge to loved ones also bereaved.

Back from Australia after the death of my dad, when laying the table for dinner, I found myself clinging on to the edge of the drawer in which we kept the cutlery, my back turned to the rest of my family, who pottered about the kitchen behind me. My eyes had suddenly become a swim of tears, my face stung with heat, the crown of my head felt tight, my chest constricted around my lungs and heart. I felt the reason for the sudden sickness of this change to be irrational, that it was mortifying such a banal thing could affect me so, and that, therefore, it was needless to upset my family by letting them see me.

“There are days where not crying in front of a new friend is a victory”

I’d been taking cutlery out from the drawer and had instinctively picked up five sets, instead of four. I’d forgotten that not all my family would be eating, that day. I’d forgotten why. We’d forever have one less place at the table, which in that moment, was an impossible pill to swallow. I realised my mistake in an instant – yet the problem was, I’d forgotten it in an instant, too – and then a handful of knives and forks had brought the shock of our new reality crashing in. One of the most inexplicable aspects of bereavement is that you do not always remember you are bereaved. Sometimes this does not always feel like a bad thing: in our old home, I would walk past what once was my dad’s study and, if the back of his chair was turned at the right angle, I could pretend that he was working at his laptop, or reading, or gazing pensively out the window. The truth can be something that we hide from, because it can sadden us immeasurably.

That picking up one too many knives and forks could cause such a painful reminder of the sudden loss of my dad, and more, could cause such an intensely physical reaction to it, was ridiculous – at least I thought it was. I felt ill and disjointed – even though it was reality, not illusion, that had suddenly broken the previously busied seams of my mind. I was being distracted by grief; it was barging in, un-knocking, certainly unwelcome at the time – but it was not the last time that it would do so.

“Grief is physically and emotionally draining work”

Working at university and continuing to mourn in a way that acknowledges feelings, but doesn’t allow them to overwhelm, is a knotty and demanding line to navigate. It is not always possible for me to get all my work done, and it is never easy for me to forgive myself for this. There are days where not crying in front of a new friend is a victory. There are classes and supervisions where an idiom, a fleeting reference to a poem or film or philosopher will remind me of my dad. And being reminded of my dad is not bad thing – not necessarily. But it is often a hard thing.

Reminders exist everywhere, which is not something I ever could have anticipated – and even in sleep, I cannot always escape the sorrow I have for the death of my father. I know that I am not alone in dreams and nightmares because of grief, that friends and family suffer and have suffered these also. It’s a difficult and alarming thing to feel as though your subconscious is working against you, and yet, as with all things concerning death, there is a strange multiplicity to it.

I am frustrated by my dreams of my dad because they are often nightmares, because even the ones that aren’t quite nightmarish disorient me when I wake up, and I begin a new process of grieving all over again. They undo the conscious work I do to process, to heal, when I am awake. And yet, if I have a dream about my dad, I often regret whatever wakes me, and wish I could have another, because I miss him, because I want to see him again. It’s a morbid and grim reality, and ugly work muddling through a day after a dream, especially a nightmare.

But none of us are alone in this. Grief is physically and emotionally draining work. Yet alongside the sad and hard reminders exist happy ones: there are things that are a joy to reflect on; there are things that taste bittersweet. There are aspects of who my dad was, and who he was to me, that I am glad to be reminded of. The human mind is a mind of associations, and when we’ve lost someone dear to us, the truth is that not all those associations will be good. But with all the bad, with all the painful, there exists a great deal of good – and more than this, you, if you are bereaved, deserve a great deal of credit for muddling through it, however messy and difficult it may feel

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025