Coping with grief line by line, page by page

Dusty covers and ancient poems can hold the most intimate memories of lost ones, writes columnist Ana Ovey

Just as, after my dad’s death, grief became one of the lenses through which I saw the world, literature has always been one of those lenses. Some of my favourite early memories include my dad sat on my bed, reading me books — or, better yet, me and my brothers sat on my parents’ bed as our dad made up amazing and outrageous stories for us. This may not be a sentiment so applicable to others suffering loss, but the written and spoken word has provided me with such consistent catharsis that, in writing about coping with bereavement, it would feel farcical if I didn’t include literature in healing.

If songs provide glimmers of wisdom, truth and relief to turn back to, films may provide whole portions of these. But there is something different in the vastness, the intimacy, of books and poetry. During the days between the news my dad had died and my flight home from Australia, my brother sent me an extract from a book. A family friend had given it to my brothers and mum; he passed it on. I was almost surprised he knew me so well, that he was aware that a cluster of words from a story would bring me, though perhaps not joy, certainly comfort.

“But sorrow doesn’t have a sell-by date”

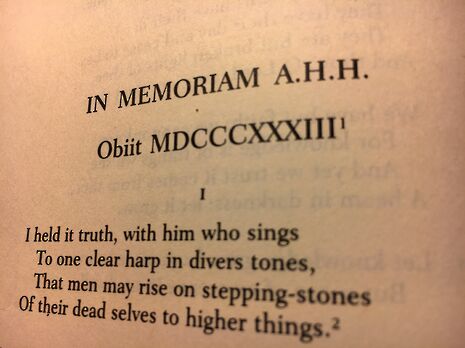

In my first week of term, one of the set texts was Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H. It’s a poem near one hundred pages long. Even in a class of eager first-year English students, frustration and defeat at the poem’s immense length seemed to be the prevailing mood. But not for me. I knew, of course, why stanza after stanza of grief could be so tedious to one who’d never experienced it. Art is of course accessible through sympathy, but sympathy is limited, and empathy exceeds it infinitely. It’s one thing to read a poem about the death of a loved one and think, “Wow, I bet that sucked”, another to read it and think, “Wow. I know how much that sucked”. As such, I loved the poem — all one-hundred and thirty-three heartbroken, melancholic, desperate cantos of it. I felt so affirmed, so vindicated, that year after year Tennyson wrote of and articulated a hurt as great as mine.

I worried, and still worry, that after the one-year anniversary of a death, you lose the right to grieve. I set out false parameters in my head: after one year, you stop crying about it to friends. After three, you stop bringing it up in conversation. After five years, maximum, you feel better about it; you no longer think about it every day; you no longer cry about it on your own.

“Grief leaves us feeling isolated, and isolation leaves us feeling defeated”

But sorrow doesn’t have a sell-by date. And I was setting myself up for failure, expecting too much of myself and too little of the people around me — who, I thought, would grow sick of my sadness. But Tennyson wrote In Memoriam for seventeen years. Seventeen. He revisits his heartache over and over. He relives it just as any griefster does, and will.

My dad read all his children the Narnia books, eagerly, and with so much joy and wonder that a love for the fantastic infected his children — at least, certainly his daughter. Even when I came home after bad days as a teenager, feeling miserable or tired or crushed, my dad would offer to read me C. S. Lewis to cheer me up. Perhaps this ought to be embarrassing to admit. But he loved literature, and I love it all the more for the pieces of him I can find in it.

I reread all the Narnia books after his death — some of it, admittedly, isn’t palatable, and Lewis’s books have faced justified criticism for their various jumbles of prejudice. But, in a children’s book, to find lines as succinct and touching as “Farewell. We have known great joys together”; “It were no virtue, but great discourtesy, if we did not mourn”; “The dream is ended: this is the morning”, is a rare and precious thing indeed, especially to those who have lost someone unspeakably precious to them. But why should words matter to us, so?

Grief leaves us feeling isolated, and isolation leaves us feeling defeated. But the end of the quote my brother sent me, “So he passed over, and the Trumpets sounded for him on the other side”, made me feel ineffably comforted, and proud of my dad, and privileged to know that he’d been a man we loved so dearly it was agony to say goodbye.

In the stories, poems and fables of wordsmiths we admire there is so much victory. Perhaps it’s the immersiveness of literature, that we invest so much in it that we are able to then, in return, gain so much. But we view the world in terms of narrative: we impose an order on what often seems terrifyingly like chaos so that there is structure and sense to it. Structure and sense seem most acutely disrupted in the face of death: yet they return to us in the clarity and close of narration, of a story well told, of a poem well written.

And so, even by their covers, I remember my dad’s face, his warmth, his love, in the books that line my shelves

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026