‘The relentless nightmares were – and continue to be – the worst part’

Our anonymous columnist on trousers, tampons and triggers

Content note: the following article describes the process of recovering from rape.

Let’s start off where I left us last week. Me – discharged from hospital and left to come to terms with The Thing I still haven’t managed to say aloud: the rape.

The next couple of days pass in a blur of bed-bound-ness, staggering to the toilet and strategising seating positions. I am filled with a nervous adrenaline which continues to inhibit sleeping and eating. Showering for the first time is horrible: I hate engaging with my body. A team of friends coordinate to provide me with constant company, ensuring someone is around to bring me the next meal, to pick things up off my floor – and to help me into trousers.

While what happened to me certainly isn’t defined by the physical injuries I sustained, they strongly shaped my experience of the early stages of recovery. The lack of mobility, combined with the antibiotics I had to take with food three times a day, tied me into a routine of self-care. Cocooning myself off from the outside world thus gave me the time and space I so urgently needed, but without such a physical manifestation of pain I doubt I would have looked after myself so well.

As the bruises on my body began to yellow, walking became more of a possibility. I sit through a seminar on Titus Andronicus and make comments on Lavinia’s rape and I feel brave. Sometimes it is less OK. I find myself wanting to cry at inopportune moments, or feeling like I’ll vomit randomly.

“Emotional recovery takes a lot of grit”

Baby steps. I have my first drink, and it is OK. I tell people I’ll go out when I’m physically able to and they look bewildered. I explain I don’t want to stigmatise it. At times I feel totally detached, as if what has happened to me is a ludicrous fantasy. I do ordinary things with other people and feel like a fake, because there’s so much I’m not telling them and my mind is elsewhere. I ring home and deliver my best impersonation of cheer.

Anger begins to build inside me. It’s a combination of rage at the ‘Me Too’ posts pockmarking my Facebook timeline, and the fact that it’s a week later and I still can’t fucking walk properly. It takes four weeks before I am able to cycle again.

Emotional recovery takes a lot of grit. Trying to get back to ‘normal’ around doing Cambridge, a healthy dose of extra-curricular activities, and catching up on a week’s worth of missed work is one of the hardest things I’ve done. There were a hell of a lot of new firsts – the somewhat questionable highlights included using a tampon again for the first time and getting with the first person post-him.

“I revisited the traumatic experience in coded nightmares and physical sensation”

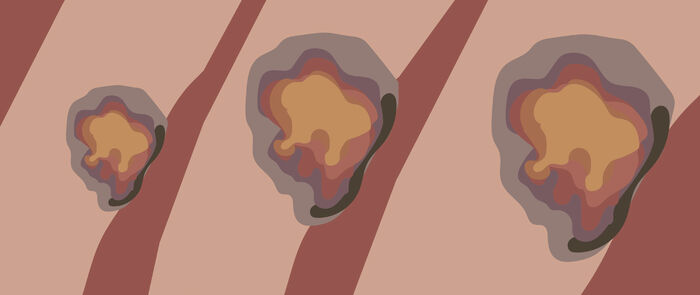

The relentless nightmares were – and continue to be – the worst part. Sexually violent, vivid dreams functioned as a kind of re-traumatisation, bringing the memories I wanted to banish to the forefront of my mind and magnifying, reimagining specific upsetting details like the bloodstains on his sheets.

Reflecting back, I’d probably describe my symptoms as PTSD-like, but at the time that wasn’t a label I particularly wanted to acknowledge. I revisited the traumatic experience in coded nightmares and physical sensations. I found some things triggering; I spent a lot of time feeling on edge or distracted.

I struggled most to get my head around the non-linear nature of recovery, fighting the urge to apply a narrative trajectory of getting progressively ‘better’. There are bad days where for a particular reason – or for no perceivable reason at all – I can’t get out of bed. I slowly learn to accept these, to not see them as failure or a sign that I’ve regressed. A migraine and some vomit later, I learn the hard way not to push myself too far: my emotionally-exhausted body will give up on me.

I chose not to seek therapy or medication to help me for a complicated set of reasons. The agreement I effectively made with myself was that I didn’t need to go to therapy as long as I continued to put effort into processing and dealing with what happened. I spent a lot of time talking to incredible friends about the event and the things which I was subsequently finding difficult. I made myself write a lot to get the ugly thoughts out of my head and onto a page where I could look at them with more objectivity. I read self-help guides and feminist books and engaged with the issue on a broader scale.

Of course, there’s no ‘right’ way of dealing with these things – this is just what’s been working for me. I spoke to another survivor, who explained she found therapy really helpful for “having someone validate my experiences, tell me that it was rape and that I wasn’t overreacting. Having someone listen to me relay the experience without judgement helped me to process what had happened”.

There are moments of immense satisfaction: pride that I am persisting, surviving. I make a group of people around me laugh, and realise that my sense of humour wasn’t a thing I’d lost. Anniversaries of the date begin to feel less like a cause for grieving and anger but satisfaction at the fact that I am putting it behind me. Slowly but surely, the rape begins to feel less all-consuming, less all-defining, but rather a part of my human fabric

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026