Fears of ‘decolonisation’ go deeper than literature

As a British citizen who feels foreign in England, Zachary Myers argues that underneath the right-wing press’s reaction to decolonisation is the same fear seen in debates over immigration

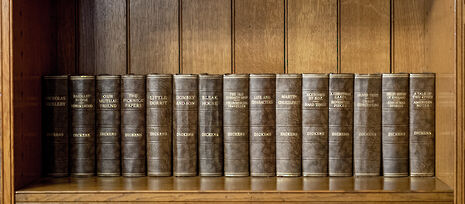

Over the last few weeks you would be hard-pressed to find a single Cambridge student who has not heard of the word ‘decolonisation’. The publication of an open letter advocating for the decolonisation of the English syllabus at Cambridge ignited a national debate. An onslaught ensued from right-wing newspapers such as The Telegraph and The Daily Mail, targeting the CUSU women’s officer Lola Olufemi and falsely characterising the letter as a student demand to remove white authors to make room for black ones. It seemed to many that students of colour at Cambridge had stormed the gates of the English Faculty and had begun to snatch every copy of Dickens and Austen in sight.

It goes without saying that nothing could be further from the truth. However, despite a half-hearted apology from The Telegraph that clarified that the letter only contained suggestions, and that these authors wouldn’t be going anywhere, people still seemed afraid of ‘losing’ these writers. In addition to the initial press reaction, this raises an interesting question: what is it that the public are really afraid of losing?

“It isn’t issues of form, metaphor, and narrative that are making people angry – it’s an issue of culture”

Even as an English student, I can’t imagine that such outrage could only be a response to the prospect of students like me not having to trawl through the entirety of Middlemarch or Bleak House. If anything, it seems that it isn’t even the work of these writers that matters, but their ‘Englishness’. It isn’t issues of form, metaphor, and narrative that are making people angry – it’s an issue of culture. When we look to study the culture of a particular society or nation, we always look to its artists. Authors like Charles Dickens and George Eliot have always been the creators of ‘Englishness’. As a foreigner, it’s the images that writers like these have ingrained into common perceptions of Britain that have given me an idea of what life in this country would be like.

For many people, the thought of ‘losing’ the writers that have been so instrumental in defining an English identity isn’t just angering, it's terrifying. It’s this fear that’s manifested in the current chaotic political climate, one which has only served to reinforce these very fears. Issues like Brexit and the anxiety over the refugee crisis have partly stemmed from a fundamental terror that mass immigration would end up ‘watering down’ a culture that was once uniquely English. If a national culture is for everyone, is it really for anyone?

That being said, as an immigrant myself, this attitude seems to be exactly the problem with English society today. Basing ‘Englishness’ on the exclusion of foreign people and foreign cultures is ignoring that ‘Englishness’ has never really been contained to England. If anything, for centuries ‘Englishness’ has been synonymous with cultural imperialism. People all over the world have been forced to fit the mould of the English culture, and it’s been the spoils of the plunder of these foreign lands that have contributed to what we consider to be ‘English’ today. If this country is going to keep chicken tikka masala as its ‘national dish’, then it needs to accept that its culture isn’t all that ‘national’. The right-wing can’t have its curry and eat it too.

“I’m mysteriously bound up in this culture, and simultaneously one of the very immigrants that some people are afraid of”

I am one of the only three people in the University from Bermuda. My country is an island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and also a ‘British Overseas Territory’ – I come from a modern-day colony. For me, ‘Englishness’ has always been a confusing concept. Not once have I ever considered myself to be ‘English’ or even ‘British’ in any way, and given the look of horror on my friends’ faces when I tell them I haven’t heard of Peep Show, Kate Bush, or the Norman Conquest, I doubt anyone here thinks of me as English either. Yet, printed in gold on the cover of my passport is the British royal coat of arms. I’m mysteriously bound up in this culture, and simultaneously one of the very immigrants that some people are afraid of.

This to me sums up part of the relevance of the ‘colonial’ narrative. The issue of ‘decolonisation’ is not just about racial diversity, it comes from a long-held fear of ‘reverse colonisation’ from countries like mine. In the last century, England has seen mass immigration from its current and former colonies on a new scale. As an example, the British Nationality Act of 1948 allowed the 800 million subjects of the British Empire to live and work in the U.K. without a visa, leading to a mass influx of these subjects into England. Perhaps to many British people, the sight of foreigners arriving by the boatload on their shores was not a pleasant one. The hypocrisy of this speaks for itself.

Decolonisation is not the ‘loss’ of British culture, it is not a ‘reverse colonisation’; it is a process of acknowledgement. It is an acknowledgement of those unheard voices who built this country’s economy and its culture. It is an acknowledgement that writers in English from around the world, these inheritors of a colonial past, have just as much of a part to play in defining England as Dickens and Austen do. Decolonisation is a movement beyond ‘English’ literature, and beyond an antiquated idea of ‘Englishness’. It is a movement towards the future, driven by an understanding of the past. As students at an institution that prides itself on being “a global community”, it seems to me that we have the responsibility of ensuring that the University is putting its money where its mouth is

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025