‘Wonders on a plane surface’

Daniel Gayne explores Britain’s greatest landscape architect’s lost vision for the Cambridge backs

It’s hard to imagine the backs as anything other than the mess of collegiate personalities that we see today. The parade of bridges, gardens, and magnificent architectural showpieces embodies the rivalrous spirit that has defined Cambridge’s entire history. But things could have been very different. Tucked away in the University’s archives is a plan for a radical restructuring of the area which would have rendered it completely unrecognisable from its current form.

Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown is by no means a household name today, but in the eighteenth century, he was one of the country’s leading landscape architects, designing many of England’s great country estates and mansions. His work focused on coherence and elegance, and he was renowned for his seamless designs which made use of the sunk fence or ‘ha-ha’ to confuse the eye into believing that different pieces of parkland, separately managed, were a unity. No wonder, then, that after working on St John’s fellows’ garden his eye was drawn to the fragmented area behind Cambridge’s river colleges, known as the backs. It is thought that Brown outlined his thoughts to influential friends, such as Dr Powell and Professor Mainwaring, who in turn persuaded the Senate in 1776 to commission him to make a plan for ‘some alterations’.

The backs had come to be between the 11th and 13th century, when what had been marshland in Roman times dried out with the canalisation and straightening of the river. Since that point, Cambridge’s colleges had slowly come to dominate the small town of Cambridge, turfing the floodplain in the 1760s and 70s to created the lawns we are now familiar with.

“An open, tree-speckled parkland space, with four paddocks stretching from St John’s to the Mill Pond”

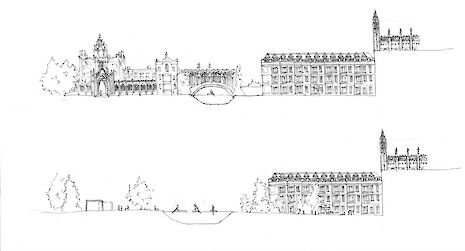

However, the colleges each developed their segments along different formal gardening principals, and Brown was tasked with creating a unified approach. The result was a plan for an open, tree-speckled parkland space, with four paddocks stretching from St John’s to the Mill Pond. At the centre would be King’s College’s Gibbs Building, recently built by Brown’s friend James Gibbs, which would play the country house in this aristocratic scene. Attention was drawn to the building by blocking off direct view of other features with strategic placement of trees.

Perhaps more radically, the Cam was to be widened substantially into a lake with two long islands. What’s more, a number of avenues and bridges were to be removed and the river by St John’s would be straightened. For his efforts, Brown was praised by Emmanuel fellow George Dyer for doing “wonders on a plain surface” at an expense “scarce wirth mentioning” – specifically a piece of plate to the value of £50. But perhaps due to the scale of the changes, or perhaps because of the college’s jealously guarded independence, the plans were not adopted, and the backs continued to let a multitude of landscapes bloom.

It’s interesting to imagine how Cambridge’s most iconic landscape would have developed if the ‘Shakespeare of gardening’ had his way. The magisterial, neo-gothic St John’s New Court, a favourite source of tall tales for punters, simply would not exist in the same form if the river’s kink had been ironed out. Contemporary oddities like Trinity Hall’s Jerwood Library are also difficult to imagine in such a carefully managed parkland, only making sense in the hodgepodge of real Cambridge.

The backs are still changing today, though plans are much more modest. In Robert Myers’s 2007 plan for the next 50 years of the landscape, the focus is not on grandiose feats of engineering, but on the removal and replanting of trees with the aim of protecting the collective health of the land

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026

News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026 Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026

Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026 News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026

News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026