A criminal addiction

Katie Williams wonders why we relish tragedy on the page and our screens – is it simply distanced adrenaline, or something more?

The Moors Murders took place over fifty years ago. When murderer Ian Brady died only a few weeks ago, coverage of the murders flooded the press once again. The stories are chilling and the murderers terrible. However, it is absurd that such an interest remains over fifty years on.

When the news broke, I found myself scanning online articles to read about the case. I read about the victims. I read about the psychology of the murderers. The facts disgusted me, but I couldn’t stop scrolling. Why? I can only conclude that, however disconcerting it may be, we are transfixed by the terrible. As Dan Brown wrote in his best-selling novel Angels and Demons, “nothing captures human interest more than human tragedy.”

I used to work as a Saturday-girl in my local library. There was a whole non-fiction section devoted to books on real-life crime. Whenever anybody took one of these books to the desk to borrow, there would be a sheepish look on their face. There is something undeniably weird about being interested in real crimes and real tragedies. Yet, when the BBC aired a disturbing dramatisation of the 2008 Rochdale sexual abuse crimes this month (Three Girls), the final episode drew 5.5 million viewers. This fact is difficult to comprehend. Television is generally considered a form of entertainment. Yet this series cannot be incorporated under this umbrella term. It is harrowing. However, millions still tuned in to feel their stomachs drop as the tragic details of the case unfolded.

“By experiencing extremes of emotion in a controlled and distanced environment, we purge ourselves of emotion in a safe way.”

How can this effect be explained? As a student of English and an avid reader, I often find myself buried in books which engage with crime, horror, and tragedy. We feel no guilt when we relish horrible novels as forms of entertainment. They are entirely fictional. There is a comfortable gap between the plot and our reality.

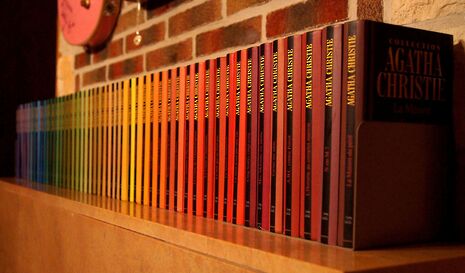

The ‘whodunnit’ has always been a popular form for the novel to take, from Arthur Conan-Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, to Agatha Christie’s murder mysteries, to modern thrillers like Paula Hawkins’s Girl on the Train. We are a culture that has been driven mad by Game of Thrones, in spite of (or perhaps because of) the explicit content. Likewise, where Shakespeare is concerned, most hold the tragedies in greater esteem than the comedies. King Lear is widely attested to be the Bard’s finest work, challenged only by Hamlet (yet another tragedy). There is hardly a single element of light in the entirety of Lear – one character concludes, “All’s cheerless, dark and deadly.”

Where fiction is concerned, we can explain this uncomfortable phenomenon in terms of catharsis. By experiencing extremes of emotion in a controlled and distanced environment, we purge ourselves of emotion in a safe way.

Alternatively, we can understand it in sterile and guiltless biological terms. There is an adrenaline rush involved in watching crime dramas and horror movies. This rush is undeniably addictive. Yet, in his book ‘Why We Love Serial Killers’, contemporary criminologist Scott Bonn argues that it is not only fictional crime which creates this adrenaline response. It applies to real-life crime stories as well. Again, this creates a certain uneasiness. Getting a kick out of real crime is sadistic. Are we sadistic?

“We think of ourselves as sofa-sleuths, and perhaps lose compassion along the way...”

Perhaps the terms I use here are too simplistic – an adrenaline rush is certainly not always pleasant. Watching Three Girls, I was forced to abandon the series mid-episode. I couldn’t stomach the content, which felt all the more harrowing given how recently the sex crimes were committed. On Twitter, many echoed my sentiment.

I do not wish to undermine the importance of the series at all – it was so important in so many ways, such as raising awareness of the failures of a social system which let vulnerable people slip through the net. Indeed, the issues the first episode raised have remained on my mind long after watching and, in a reluctant sort of way, I feel the need to finish the series, if I can.

This paradox might be what we experienced when the Moors Murders returned to the news, when we were drawn to the familiar stories all over again. Yet, I think part of the reason why the public and the press haven’t been able to forget this case is because it has been so inconclusive. Brady is an inexplicable character. We cannot understand his horrendous motives.

Many find Myra Hindley even more inexplicable simply because she is a woman. Perhaps we react in this way because, statistically, far fewer violent crimes are carried out by women than by men. Yet, more significantly, a woman who murders children rips up society’s lingering stereotype of the woman as mother and carer. This gender prejudice where crime is concerned has resulted in society branding most female murderers as ‘mad but not bad’. Madness is easier to comprehend than the alternative.

Conversely, Hindley has been caricatured as a folk devil. Epitomising her as evil allows society to avoid looking at her like a regular human being. Seeing her as ‘other’ means that people don’t have to rationalise or understand her thinking. Therefore, she remains inexplicable.

Likewise, mystery remains insofar as the families involved were never given absolute closure. One of the bodies was never found. Most human-beings seem to share an innate curiosity. We also desire completeness. Yet, the Moors Murder cases have left large elements of mystery. Driven to obsession by our curiosity, we scroll through the stories as if we will be able to spot some detail that everyone else has missed. We think of ourselves as sofa-sleuths, and perhaps lose compassion along the way

News / Proposals to alleviate ‘culture of overwork’ passed by University’s governing body2 May 2025

News / Proposals to alleviate ‘culture of overwork’ passed by University’s governing body2 May 2025 Lifestyle / A beginners’ guide to C-Sunday1 May 2025

Lifestyle / A beginners’ guide to C-Sunday1 May 2025 News / Graduating Cambridge student interrupts ceremony with pro-Palestine speech3 May 2025

News / Graduating Cambridge student interrupts ceremony with pro-Palestine speech3 May 2025 Features / Your starter for ten: behind the scenes of University Challenge3 May 2025

Features / Your starter for ten: behind the scenes of University Challenge3 May 2025 News / Varsity survey on family members attending Oxbridge4 May 2025

News / Varsity survey on family members attending Oxbridge4 May 2025