Going native: growing up in Corsica

Growing up on the French ‘Island of Beauty,’ Esmé O’Keeffe learned more than just French and long division

If you have ever visited Corsica, naffly referred to by the French as the ‘Island of Beauty,’ you probably spent a week bobbing about aboard a yacht in the glittering turquoise waters. Maybe you even attempted the famous GR20, Europe’s toughest hike. My experience of Corsica was different. When I was a child, I ‘went native.’ Switching between cultures and mores and laying roots only to be temporarily uprooted was an experience which at the time was rather difficult, but which in retrospect has been one of the most valuable experiences of my life.

I first arrived in Corsica as an 8-week old bundle, and slept in a drawer since my parents had no cot. From that day on, I went on to spend my childhood hopping in a triangle between Yorkshire, Italy, and Patrimonio, the wine-producing village in the north of the island, where I did a couple of stints in the local primary school.

Primary school in Corsica was like nothing else. In terms of equivalent educational trends in Britain, it was somewhere between the Victorians (with their punishments and rote-learning) and the progressive era of the 1970s (the days of lax attitudes and calling teachers by their first names) but, besides learning French, the most valuable lessons learned were cultural and social, rather than educational.

“I learned that there are often two ways of doing something, and that neither one is necessarily right, just different.”

The day began with kissing the teacher standing guard at the front door, both sides, Mediterranean-style. If you were lucky, you would be greeted with ′Bonjour ma caille’ (‘my quail’) or ’ma puce’ (‘my flea’). If you were unlucky, you just got the kiss. Break time consisted of playing football in the dust (so far so normal), whilst the teachers smoked and gossiped in the sun, flicking ash off their jeans. At 11:30am I scrambled home to the top of the village for lunch, returning again at 13:30 for afternoon lessons. Officially, the academic year finished on 2nd July, but it was considered odd (and a nuisance for the teachers who wanted to be getting on with their summer break) if you were still there in the last few weeks of June. As the teachers let playtimes expand to swallow up lesson time entirely, it was time to take the hint and drop out.

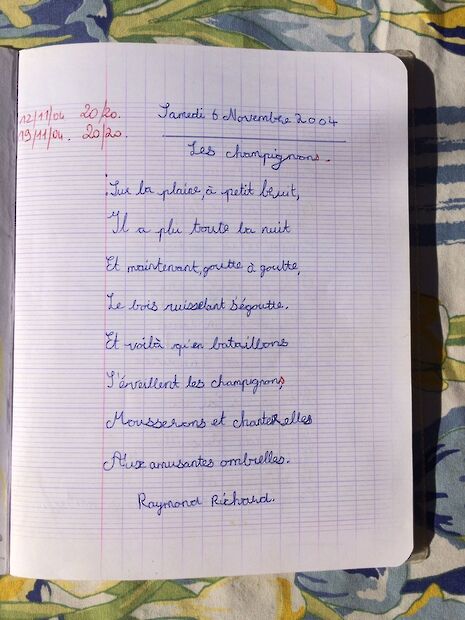

The education itself was a far cry from my British primary school, with its Key Stages, SATs tests and regular government inspections. In Corsica, one of my first challenges was learning to write like a Corsican. I spent hours mastering the loopy, elaborate letters of French orthography. Then came the dictées (‘dictations’), the draconian spelling tests to which my grandparents had been subjected and which went out of fashion in Britain half a century ago. Rote-learning always has been and remains a key part of French primary education, and every Friday each pupil took it in turns to stand in front of the class and recite a poem selected from the French classics which we had been made to write out, illustrate, and memorise. Knees knocking and voices quivering, we were then scored out of twenty. If you failed drastically, you were sent to the corner and made to face the wall – a somewhat Victorian punishment also doled out to any child caught talking when they weren’t supposed to.

Although maths lessons were surprisingly advanced, science lessons focused on learning to identify different types of mushrooms (to this day, I can tell my trumpet-style chanterelles from my poisonous amanite, my cèpes and my blue-tinged bolets). It was a bespoke education: we were growing up in the maquis, the hostile but fragrant shrubland which characterises the Mediterranean.

If you finished your worksheet, you were told to “sit there quietly and draw something nice”; there was no room in the regimented and methodical programme for challenging bright children, and certainly no room for ‘thinking outside the box.’ However, there was a creative element: weekly art lessons consisted of copying the masterpieces of famous French artists, trying our 7-year-old hand at imitating the perspective of a Cézanne still life, or the lurid fluidity of Matisse’s La Danse. In some ways, it was an oddly cultured and holistic education: on a literary front, we were also introduced to the fables of Jean de la Fontaine – none of those fluffy Biff, Chip and Kipper books which we were force-fed for the sake of ‘literacy’ in England.

The sports lessons were somewhat eccentric. Besides sailing and volleyball, for the older years, ‘sport’ consisted of scaling the side of the school. One of the teachers, a gruff and wiry smoker, was an enthusiastic rock climber: his class would harness themselves up and take it in turns to navigate the hand and foot holds punctuating the façade of the building, all the way up to the roof.

Also new to me were the Corsican lessons. Sitting cross-legged in a circle on the 1950s tiles, every week we chanted our way through Corsican vocabulary worksheets – ’a cupulatta’ (‘tortoise’), ’lumaca’ (‘snail’) and ’cignale’ (‘wild boar’ – there it is again). While as a French département the island’s official language is French, Corsican (which bears many similarities to the Tuscan dialect) has been experiencing something of a patriotic revival over the last few decades. Corsicans have kept their language alive through the promotion of their musical and wider cultural identity, a drive reflected in the strong nationalist and independence movement led by the FLNC since the 1960s.

In the winter of 2004, the ferry companies and maritime unions went on strike, amounting to a small crisis in Corsica. We caught the last ferry off the island to make it back to the UK in time for Christmas. There was talk of petrol shortages, and people raided the shelves of the local épiceries to stock their larders. Then in March 2004, it snowed. We were given the week off school, there were power cuts in the evenings and we cooked spicy merguez sausages on the open fire by candlelight. It was a far cry from the civilisation back in the UK.

But, little children are like plasticine: I had embraced every bit about living in Corsica, and I felt Corsican. When I returned to England, I tried to kiss all the other 9-year-olds by way of greeting. They scrubbed at their cheeks and called me weird. I may have minded a bit at the time, but I soon learned to be proud of my ‘otherness,’ and I learned to enjoy being different: after all, it was (and still is) a key to a world very dear to me. At the same time, I learned that in order to fit in, it helped to be one way with one group of people and another way with others. I became adaptable, and open-minded.

I learned that there are often two ways of doing something, and that neither one is necessarily right, just different. Instead of having no roots, I have multiple roots. My experiences in Corsica have moulded me into who I am today: if it were not for my parents’ fear that that I would grow up monolingual, and that eccentric primary education I received in Corsica, I would not be here at Cambridge today. But best of all, whilst my passport may be British, I felt as though I gained access to a second identity: not French, but Corsican

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025