Why fashion has work to do in dismantling systemic racism

A black square isn’t enough – fashion must take an introspective look at itself

For all their #blackouttuesday black squares and statements of ‘We hear you, we stand with you’, fashion labels have had a muted reaction to the Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd. High-street brands and designers alike have been criticised in recent weeks for vague and empty statements that avoid directly addressing issues of systemic racism and police brutality, for sharing aesthetic graphics and Maya Angelou quotes with no tangible commitment to the cause (financial or otherwise), or for a lack of response altogether. From Louis Vuitton to Zara, companies have traditionally shown a reluctance to engage with socio-political causes in favour of maintaining revenues and a certain brand image - a claim of impartiality would presumably pander to a wider customer base. What is not acknowledged, however, is that much of the fashion industry is not tackling this issue from a starting point of neutrality, but of anti-blackness, endemic in many white supremacist practices that they must now confront and work to rectify.

Fast-fashion labels notoriously exploit the labour of people of colour using a workforce of garment workers in low-wage economies like Bangladesh, China, Vietnam and Cambodia, many of whom benefit from few to no social protections and are forced to endure dire working conditions. Average wages in the large garment-producing economy Bangladesh stand at 35p an hour (Guardian), far below the living wage. Furthermore, in an era of Covid-19, not only are the workers not afforded paid sick leave, but many are being suspended without pay altogether, as brands like Topshop and URBN Group (Urban Outfitters, Free People and Anthropologie) cancel orders. In The Style came under fire for releasing a Black Lives Matter charity t-shirt, whose creation surely relied heavily on the cheap labour and exploitation of garment workers.

And this is far from the first time that a brand has come under fire for such hypocrisy; the list of labels that have misappropriated and profited from black culture whilst casting few to no black models in their shows or campaigns is endless. Valentino was accused of cultural appropriation after its ‘tribal Africa’-inspired spring/summer 2016 collection saw a line-up of 87 models take to the catwalk wearing cornrows, of which just eight models were Black. Marc Jacobs faced backlash after a cast of majority white models walked its spring/summer 2017 catwalk wearing dreadlocks, a controversy the designer dismissed at the time, but has since apologised for. And earlier this year, Comme Des Garçons also faced calls of cultural appropriation as mostly white models hit the autumn/winter 2020 runway in cornrow wigs.

Equally, the work of black creatives is often used without due credit, let alone remuneration; fast-fashion label Fashion Nova last year came under fire for plagiarising designs from black artists and designers like Luci Wilden, Destiney Bleu, Jai Nice and Briana Wilson. Reebok touched on the debt owed by the fashion world to the black community in their statement: ‘Without the black community, Reebok would not exist.’

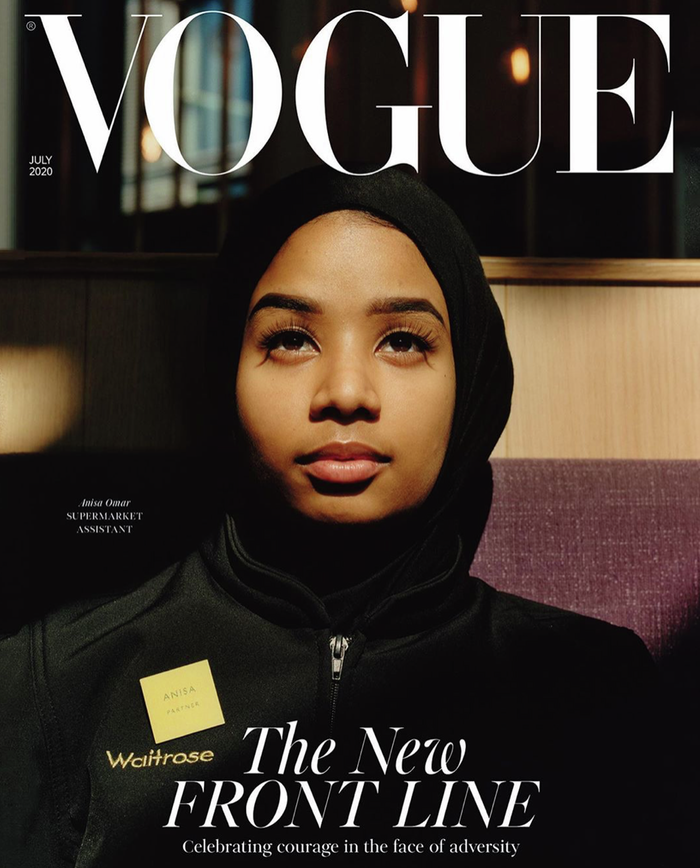

Whilst the industry has yet to make space for Black designers in the creative process, many have in recent weeks pointed out performative shows of solidarity from brands who, from a quick scroll through their Instagram feed or a glance at YouTube, evidently have yet to include Black models in a meaningful way in their catwalk shows and campaigns and who have consequently had a hand in perpetuating white Western beauty ideals. Where models of colour are used, colourism persists; light-skinned or biracial models are given preference (again, Fashion Nova does not fare well on this front), whilst models like Naomi Campbell, Chanel Iman and Mariah Idrissi have spoken out about the use of token Black or hijabi models. Following Ferragamo’s statement against racial injustice, actor Tommy Dorfman accused the label of intending to whitewash black models, writing on Instagram: ‘I heard direct [sic] from their creative director that they asked if, in Photoshop, they could make a black model white.’

And these few areas only scratch the surface in terms of the change required for a diverse, inclusive and anti-racist industry. From hiring practices and the number of people of colour in leadership roles at luxury fashion houses (Virgil Abloh, Olivier Rousteing and Rihanna come to mind as the only black designers at the helm), to workplace culture and the treatment of black customers in shops, brands must review every aspect of their daily operations. Recent allegations by former employees of Urban Outfitters and Anthropologie regarding the racial profiling of customers caused the brands’ statements of solidarity to ring hollow and only testified to the importance of a re-examination of all company practices. The industry is beginning to see steps in the right direction; after a year of design-related controversies (lest we forget Burberry’s noose hoodie and Gucci’s blackface jumper), Burberry, Gucci, Prada, H&M and several others have introduced diversity councils and initiatives. L’Oréal has invited Munroe Bergdorf to sit on its diversity board; the French label’s initial post in support of the anti-racist movement was deemed hypocritical after Bergdorf revealed that she was dropped by the brand in 2017 for speaking out against racism. The new #PullUpOrShutUp initiative challenges brands to submit their diversity statistics, holding them to account for black representation in their organisations. So far, beauty companies like Revlon, Kylie Cosmetics and Milk have responded to the call for transparency and shown where there is work to be done.

When it comes to the Black Lives Matter movement, consumers have demanded that both luxury and fast-fashion labels put their money where their mouth is. Glossier was widely held up as a paragon, as one of the first to tap into the collective consciousness and commit a sum of $500,000 to organisations combating racial injustice and $500,000 to support black-owned beauty businesses. Several fashion giants including Stella McCartney, Alexander McQueen, Kith and Supreme followed suit with donations and pledges all around. Marc Jacobs’ reaction to the looting and vandalism of his Rodeo Drive store, in the light of his 2017 fiasco, shows that, indeed, it’s never too late to start: ‘Property can be replaced, human lives CANNOT,’ he wrote on Instagram.

It is not only empty PR moves and a reluctance to show real solidarity with socio-political causes, then, that fashion must answer for, but its own discriminatory practices. Though an industry that has seen change for the better in recent years, it has a long way to go to the inclusive and egalitarian future it touts as its present moment. A future in which diversity means more than tokenism, more than ticking boxes and more than mere optics. So, if you do stand for racial equality, don’t tell us in a pretty graphic. Take radical action and show us.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026