How literature informs fashion

In times of uncertainty and anxiety, fashion can provide a welcome form of escapism. In that spirit, Fashion Editor Mier Foo reflects on literature’s enduring influence on the fashion world.

In the age of social media, contentious acts of self-mythologising are often conflated with Art. From the sponsored looks of influencers to the wealth of internet subcultures that celebrate homogeneity in fashion, dress has become a means of signalling rather than a conduit for true expression. In an essay for the New York Tribune, Oscar Wilde famously declared that “Fashion is ephemeral. Art is eternal.” In today’s hyper-exposed world of fast fashion, it almost seems as if anything goes, which compels us to question, just as Wilde did in 1885 - what is fashion really?

In fiction, fashion is symbolic; clothes become a form of context where dress is often used to represent a character’s transformation, power or privilege. As Virginia Woolf rightly states in Orlando, “Clothes have more important offices than merely to keep us warm; they change our view of the world and the world's view of us.” Poised at the intersection between art and fashion, literature has spawned some of the fashion world’s most enduring icons: Anna Karenina, Orlando, Holly Golightly, Lily Bart… the list is endless. Woolf herself in recent years has also become a muse for designers. She was name-checked at Givenchy’s Spring/Summer 2020 haute couture show in Paris, dubbed an ode to the “sapphic romanticism” between her and Vita Sackville-West, and cited as the “ghost narrator” of the forthcoming Met Gala and exhibition, About Time: Fashion and Duration.

"Perhaps fashion’s fixation with writers stems from their ability to dissect an outfit like a shapely sentence"

Her novel Orlando with its gender non-conforming hero seemingly preempts the trend of androgyny in fashion and the rise of modern masculinity which seeks to embrace fluidity in gender expression. Co-ed fashion shows have been gaining traction as well with industry giants such as Burberry, Gucci, Coach, Bottega Veneta and recent convert Versace taking up the trend. Woolf was preoccupied with what she termed ‘frock consciousness’, which sought to delineate the inherent performativity of clothing. In her diary entries, she repeatedly turns over “the eternal, & insoluble question of clothes”. “My love of clothes interests me profoundly,” she writes. “Only it is not love; and what it is I must discover.” She was acutely attuned to the Modernist questions of self-representation, particularly the conflict between selfhood and expression.

Clothes for her represented a form of social artifice. Her renowned stream of consciousness style narrative explores the performed femininity she ascribes to certain articles of clothing: “Though I hate putting on my fine clothes, I know that when they are on I shall have invested myself at the same time with a certain social demeanour—I shall be ready to talk about the floor & the weather & other frivolities, which I consider platitudes in my nightgown.” Similarly in Mrs Dalloway, the “silver-green mermaid's dress” her character Clarissa wears to the party she is hosting defines her vivacious persona and allows her to navigate the “lolloping waves” of guests with ease. Through her characters, Woolf shrewdly exposes the potential trappings of using clothing to represent character and the perils of associating attire with one’s identity.

Perhaps fashion’s fixation with writers stems from their ability to dissect an outfit like a shapely sentence, and the alluring hold they can have on a reader. From an early age, novels have imbued me with an understanding of how to ‘read’ an outfit. In Anna Karenina, the eponymous protagonist changes into a “simple lawn dress” which her sister-in-law studies carefully, gauging the difference between Anna’s easy poise and her own perceived inadequacy as in her own words, “she knew what such simplicity meant and cost.” Conversely, the conspicuous consumption prevalent in Edith Wharton’s novels attests to the earnest sentiment of her sartorially conscious heroine that “a woman is asked out as much for her clothes as for herself.” In a similar vein, it is Gatsby’s “gorgeous pink rag of a suit” that reveals the working-class origins he desperately tries to escape. “An ‘Oxford man!’” Tom exclaims, “Like hell he is! He wears a pink suit.”

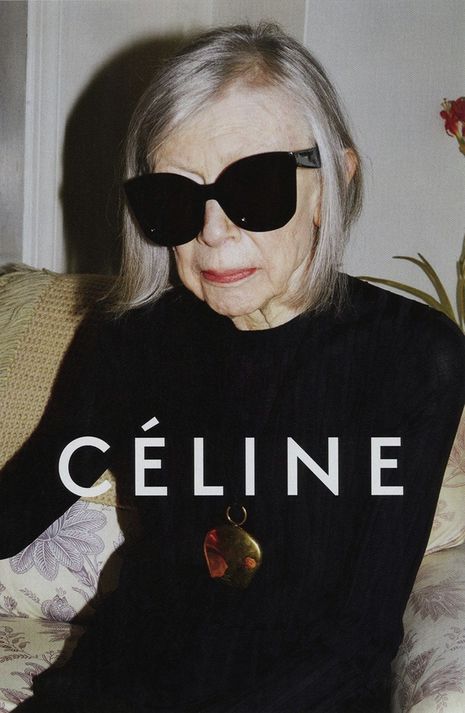

In 2015, French label Céline made headlines for featuring the writer Joan Didion, then eighty years old, in an ad campaign with her face hidden behind a signature pair of dark sunglasses. The move generated a media frenzy which ricocheted beyond the fashion world cementing Didion’s position as much style icon as lauded author. The popularity of the ad was unprecedented given that much of its target audience includes millennials or members of Generation Z who would have been unfamiliar with her work.

However, upon closer inspection, the decision makes perfect sense. In many ways, Didion is the ideal Céline muse with her sensual yet austere manner. Her quiet glamour and carefully crafted personal style are archetypal in Phoebe Philo's artfully honed aesthetic. As Nathan Heller writes in an essay titled “Why Joan Didion Matters More Than Ever” for Vogue, “Her controlled first person helps imbue the writer’s habits with the lambent glamour of a lifestyle-magazine spread”.

Didion seemed to realise early on the importance of cultivating a sense of style which carries across beyond the page and others have seemed to follow suit. Novelist Donna Tartt’s sharp turn of phrase mimics the crisp tailored suits she favours, while Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's penchant for graphic dresses is evocative of her expressive prose. In a hallmark fashion moment, the author’s TED talk entitled ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ was also prominently featured as a slogan on T-shirts in the Dior’s 2017 Spring show in a decisive move which marked Maria Grazia Chiuri’s debut as the brand’s first female creative director.

Fashion has always looked towards literature as an archive of inspiration. In today’s image-saturated world, where everyone is documenting their supposed lives on social media which the cult of celebrity has christened a form of performance art; brands could well benefit from looking towards literature as a guide on how to rise above the cacophony and cultivate enduring appeal. As Evelyn Waugh rightly put, it is the “suggestion of the haphazard” — be it a marked personality or a vague recalcitrance, that raises an outfit ‘high above the mere chic of the mannequin”.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026