Kettle’s Yard: The Louvre of the Pebble

Katy Lewis Hood is impressed by this new exhibition at Kettle’s Yard

If you haven’t discovered it yet, Kettle’s Yard is one of Cambridge’s oddities, tucked away next to St Peter’s Church on the corner of Castle Street, nestled amongst trees. Jim and Helen Ede bought the four then-derelict cottages in 1956 and created a new home for themselves, filled with contemporary art. The house contains works by Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Joan Miró, David Wallis and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, to name but a few, and remains in the state in which the Edes left it in 1973. The Edes made their house a work of art in itself, utilising the visual potential of space and light rather than leaving an empty frame for their art collection. In a similar way, but with very different results, the art of Kettle’s Yard’s new exhibition ‘Beauty and Revolution: The Poetry and Art of Ian Hamilton Finlay’ utilises the visual potential of words and surfaces in art and poetry.

Concrete poetry involves arranging words on the page – their size, shape, and layout. It dates back to classical antiquity, reworked through radical twentieth century literary movements such as Futurism and Dada. In these later forms, concrete poetry can be controversial, sometimes consisting of a single word or even a single letter on a page, raising questions as to what constitutes art and meaning.

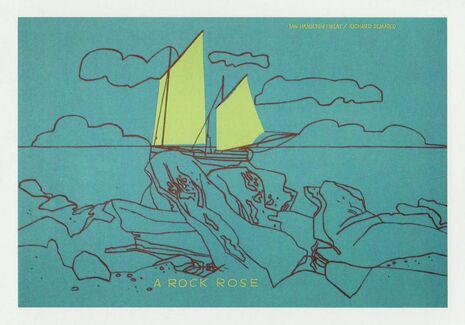

Finlay printed concrete poems through the Wild Hawthorn Press. In ‘Acrobats’, the individual letters of the word ‘acrobats’ are screen-printed diagonally across the page, performing visual acrobatics. In ‘Sea Poppy 1’, the registration numbers of warships are arranged like a flower, exploring the tension between modern weaponry and pastoral harmony. ‘Wave/Rock’ is particularly satisfying aesthetically: the words are sandblasted into the glass, with the letters of ‘wave’ rising and falling unevenly and the letters of ‘rock’ clumped together, dense, at the other end of the piece. The works have a clarity and precision that corresponds with the minimalist gallery space, exemplified by ‘Xmas Star’, previously displayed at Kettle’s Yard in 1969. This screen-print features a ship, a recurring theme in Hamilton’s work, with clean lines and a poem consisting of a series of maritime abbreviations and codes. Other themes include revolutionary slogans, and the natural world.

Finlay’s work tests the limits of what counts as poetry and what counts as visual art. He creates a landscape for words in which they can operate as emblems, open for multiple interpretations. This word-image landscape was realised in Finlay’s garden in Pentland Hills, Edinburgh. Known as ‘Little Sparta’ after a lengthy battle with Strathclyde Regional Council over its purpose, the garden is shown in the exhibition in ‘Stonypath Days’, a 16mm film produced by Stephen Bann. It is a strange, idyllic place: poems, phrases and puns are carved into stone in classical style, models of warships lurk amongst the shrubs, and all is surrounded by trees and flowers with a view of the hills. It was Finlay’s movement into carving that led him to engrave ‘Kettle’s Yard/Cambridge/England is the/Louvre of the/pebble’ onto a flat stone in 1995, now included in the permanent collection in the house.

‘Stonypath Days’ cuts from rock to flower to sundial and back again, on loop in a bare room with rain streaming at the windows. Both Jim Ede and Ian Hamilton Finlay, whose friendship began at the ‘First International Exhibition of Concrete, Kinetic and Phonic Poetry’ at St Catharine’s College in 1964, sought to create an environment, almost a temple, in which art could be collected, selected and displayed outside of the formal demands of galleries. However, neither Kettle’s Yard nor Little Sparta is really ‘outside’ – they are intimate spaces bearing a trace of their creators. In this sense, it is apt that Stephen Bann’s private collection of Finlay’s work is being exhibited in the space alongside another open, private collection in the Edes’ house. Both hold a modest, succinct charm. You might have enough knowledge of art to be able to identify the works on display in the house without labels, or you might not. You might have a view on whether words become poetry because of their environment and presentation, or you might not. In any case, Kettle’s Yard as a setting allows the ideas of Ede and Finlay to be combined and contrasted as if in conversation with each other, replicating the connection and difference begun fifty years ago.

‘Beauty and Revolution: The Poetry and Art of Ian Hamilton Finlay’ is on at Kettle’s Yard until 1 March 2015. The house and gallery open Tuesday-Sunday, 11.30am-5pm.

Features / Cold-water cult: the year-round swimmers of Cambridge21 June 2025

Features / Cold-water cult: the year-round swimmers of Cambridge21 June 2025 Comment / Good riddance to exam rankings20 June 2025

Comment / Good riddance to exam rankings20 June 2025 Theatre / Do Cambridge audiences actually get theatre? 22 June 2025

Theatre / Do Cambridge audiences actually get theatre? 22 June 2025 News / Magdalene evicts pro-Palestine encampment24 June 2025

News / Magdalene evicts pro-Palestine encampment24 June 2025 Lifestyle / What’s worth doing in Cambridge? 19 June 2025

Lifestyle / What’s worth doing in Cambridge? 19 June 2025