An American in Cambridge

The artist James Whistler tried to rid his work of pity and love. visits a new show of his prints and discovers a gentler side to a man with many enemies

As with many of the Impressionists, Whistler’s work often comes across as something of a paradox. The prints and paintings show a refined delicacy, yet they stem from a background of great passion and controversy. This survey of prints of people in the Fitzwilliam collections highlights not only some of the close personal friendships he formed through his art, but how he tore many of these apart through his strong views and biting wit.

The son of an American railway engineer, Whistler always seemed keen to play the part of the foreign aristocrat. After being thrown out of West Point Military Academy, he worked as a military draftsman, learning etching as a US Navy cartographer, before deciding to become an artist. He felt that America did not have enough respect for fine art, and his obsession with the artist’s place in society led him to cross the Atlantic in search of success. In England and France he was to find fame and recognition, yet his fondness for ridiculing friends and critics alike was ultimately to lead him to ruin.

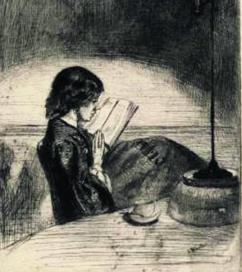

Of the many enemies that he made, the ten prints in the exhibition of fellow etcher Seymour Haden and his family stand out. These are tender and beautiful prints, recalling Rembrandt in their atmospheric use of light and shade as well as Japanese art in their decorative simplicity. This did not stop the friends falling out over Whistler’s outrageous bohemian lifestyle; the hand list gleefully notes that five years after the last print was made Whistler was banned from seeing his sister (Haden’s wife), and three years later Haden was pushed through a plate glass window after the two fought in a Paris cafe.

Interestingly, the lively personality does not 'Reading by Lamplight', James Whistler, 1985

Interestingly, the lively personality does not 'Reading by Lamplight', James Whistler, 1985

come across at all in the prints.

As he put it,"Art should be independent of all claptrap - should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like”. As a result, despite the artist’s stormy private life the prints offer an objective look at their subject; friends and strangers stand alike in decorative harmony.

It is also wonderful to see original copies of Whistler’s satirical pamphlets and lectures (including The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, from which the exhibition takes its title). The most notorious incident recorded by these is his attempt to sue the critic John Ruskin for libel after he called him a “coxcomb... flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”. Ruskin was one of the highest authorities on art at the time, making this move rather unwise. Whistler argued brilliantly and won the case, but was awarded damages of only one farthing, ruining him financially.

Despite the ruin it brought, his willingness to stand up to - and brilliantly ridicule - many of his critics lives on as a testament to the faith he had in his art, with his defence helping prepare the way for many artists to come. When asked by Ruskin if “The labor of two days is that for which you ask two hundred guineas?” Whistler’s response was a perfect justification for a “less finished” modern art: “No”, he replied. “I ask it for the knowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime.”

Sam Rose

“The Gentle Art - Friends and strangers in Whistler’s Prints” is on at the Fitzwilliam Museum until 13 January 2008.

News / Students clash with right-wing activist Charlie Kirk at Union20 May 2025

News / Students clash with right-wing activist Charlie Kirk at Union20 May 2025 Comment / Lectures are optional so give us the recordings14 May 2025

Comment / Lectures are optional so give us the recordings14 May 2025 News / Wolfson abandons exam quiet period, accused of ‘prioritising profits’ 17 May 2025

News / Wolfson abandons exam quiet period, accused of ‘prioritising profits’ 17 May 2025 Features / A walk on the wild side with Cambridge’s hidden nature18 May 2025

Features / A walk on the wild side with Cambridge’s hidden nature18 May 2025 News / News in Brief: quiet reminders, parks, and sharks 18 May 2025

News / News in Brief: quiet reminders, parks, and sharks 18 May 2025