The Satanic Verses and the death of the British multicultural ideal

Otto Bajwa-Greenwood surveys the impact of Salman Rushdie’s controversial novel on British multiculturalism

The publication of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1988 is often highlighted as a pivotal moment in the history of literary freedom. It marked an important episode in which the values of liberal culture – with its emphasis on rationality, choice, and the sovereignty of the individual – were again forced to justify themselves against an onslaught of criticism. However, the Rushdie affair, also shed a light on the simmering tension of race relations across British society. Rushdie’s novel revealed the fragility of the UK’s multicultural ideal, raising questions of integration that still struggle to be answered today.

For context, Rushdie, who self-describes as a lapsed Muslim, was declared by his multiple detractors to have crossed the line of creative freedom by venturing into a derogatory caricature of Islam. Although the author denied blasphemy, describing his novel as “a secular man’s reckoning with the religious spirit,” The Satanic Verses was regarded by many as a contemptible act of provocation. Rushdie’s novel deliberately conflated the prophet of Islam and Satan in the personified characters of Gibreel and Chamcha. Moreover, Rushdie also satirically depicted a businessman called Mahound (a medieval Europeanisation of the name Mohammed) in a blatantly sexualised fashion, hinting at homosexuality and unholy carnal liaisons.

“Rushdie’s novel deliberately conflated the prophet of Islam and Satan in the personified characters of Gibreel and Chamcha”

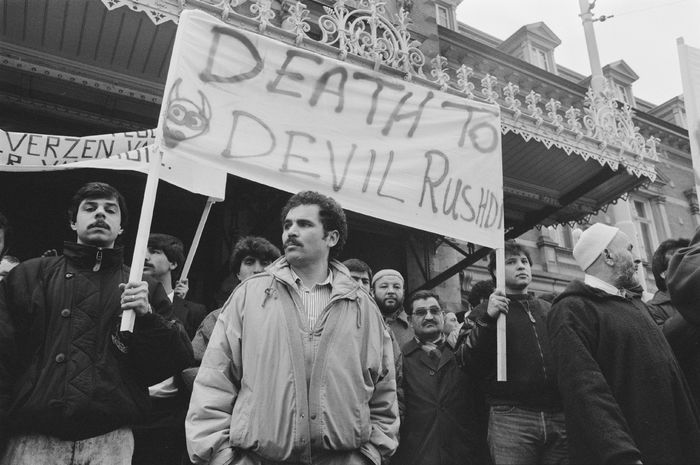

Only a few days after the book’s publication, Hesham El Essawy, Chairman of the Islamic Society for the Promotion of Religious Tolerance, anticipated the furore that was to unfold by declaring the book a “monster” that would grow to something “uncontrollable.” Multiple protests erupted across the UK. In the Bradford Riots of January 1989, more than 1000 copies of the book were burnt. The book also attracted world-wide controversy. India, Pakistan, and South Africa banned the book within weeks of its publication and tensions reached their climax on 14 February 1989 when the Ayatollah Khomeini (leader of Iran) issued a fatwa ordering Rushdie’s death. This precipitated an international crisis. Iranian demonstrators stoned the British Embassy in Tehran, severed all diplomatic relations with Britain, and an Iranian cleric offered £1 million for Rushdie’s assassination. In turn, the Ayatollah’s support vindicated the outrage felt by some members of the UK’s Islamic community. In an interview for the Sunday Mirror, five days after the fatwa was issued, a Muslim man from Manchester declared on the record that “[Rushdie] has offended all Muslims [...] If I met him tomorrow, I would kill him”. Rushdie was forced into hiding, and has retained protection for the rest of his life.

Long before the book’s publication, Britain had been the site of serious racial conflicts. In 1958, there had been the Notting Hill Race Riots in West London; the 1977 Battle of Lewisham in South London; the inner-city race riots of the 1980s, and in 1985 the Broadwater Farm confrontation in Tottenham, North London. Moreover, Enoch Powell had delivered his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in 1968, and Thatcher declared the country “swamped” by immigrants in 1978. However, the outrage caused by The Satanic Verses ushered in a new pessimism in the possibility of redressing these social rifts. Before 1989, multiculturalism had been forwarded for over twenty years by liberals and left-wing advocates as a muscular solution to the racial divides that beleaguered society. In a famous speech delivered in 1966 by the then Home Secretary, Roy Jenkins, ethnic integration was the ideal, presented “not as a flattening process of assimilation but as equal opportunity, accompanied by cultural diversity, in an atmosphere of mutual tolerance.” The Satanic Verses’s fallout not only revealed that this harmonious ideation proved to be perilously short lived, but marked an abandonment of the hope that people could live alongside each other with their different cultures and traditions. The book forced people to take a side, and in doing so, actively confront their own allegiances.

“The book forced people to take a side, and in doing so, actively confront their own allegiances”

Despite hopes of pluralism, to many multiculturalism felt more like an ill-thought-out compromise, forcing people to sacrifice their own values and identities. In British communities, any form of censorship towards the book felt incompatible with the values of individual sovereignty and free speech. Even Roy Jenkins was compelled to doubt his own earlier judgement and retreat into his own ranks, admitting in 1989 that “we might have been more cautious about allowing the creation in the 1950s of a substantial Muslim community here.” In Muslim circles, Kenan Malik has argued that “until the 1980s, few Muslim immigrants to Britain […] thought of themselves as belonging to any such thing as a Muslim community”. It was only through the controversy of The Satanic Verses that people entrenched themselves in the security of their religious and communal traditions. As expressed by the Chairman of the Bradford Council of Mosques, the divisiveness caused by Rushdie’s book meant that “we’ve found ourselves as Muslims”.

Despite Rushdie stating in a 2019 interview that he felt things had moved on since the events of the 1980s, claiming that there were “other things to be frightened about – and other people to kill,” in August 2022 a violent attack was made on Rushdie by a Muslim extremist. Despite never having read The Satanic Verses, the attacker stabbed Rushdie, causing him to lose sight in one eye.

This event raises considerations as to whether we are still living in the shadow of 1989. These days, multiculturalism, at least within left-wing circles, loosely limps along as a social ideal. But without any real conviction and government commitment it is intensely vulnerable. As the Rushdie Affair demonstrates, governments need to seriously answer how they can facilitate and encourage the co-existence of distinct cultural identities. To inadequately take a stand on this core issue of cultural compatibility is to complicitly permit division and segregation, leaving Britain as a poorer and less enriched society.

News / Pro Vice-Chancellor leaves Cambridge for Research Ireland 16 May 2025

News / Pro Vice-Chancellor leaves Cambridge for Research Ireland 16 May 2025 News / Wolfson abandons exam quiet period, accused of ‘prioritising profits’ 17 May 2025

News / Wolfson abandons exam quiet period, accused of ‘prioritising profits’ 17 May 2025 Comment / Lectures are optional so give us the recordings14 May 2025

Comment / Lectures are optional so give us the recordings14 May 2025 Features / A walk on the wild side with Cambridge’s hidden nature18 May 2025

Features / A walk on the wild side with Cambridge’s hidden nature18 May 2025 News / Students clash with right-wing activist Charlie Kirk at Union20 May 2025

News / Students clash with right-wing activist Charlie Kirk at Union20 May 2025