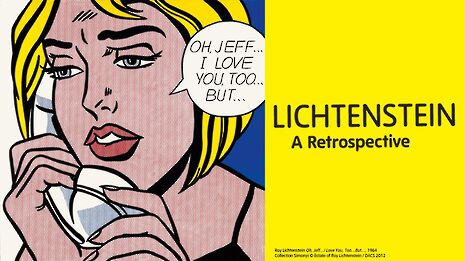

Oh, Jeff, I Love you too… but Whaam!

David Godwin takes a look at the Tate Modern’s Roy Lichtenstein retrospective.

Google ‘Pop Art’, speak to any purveyor of the form, or read any article on the subject and if Roy Lichtenstein isn’t mentioned, something is amiss. Lichtenstein’s works, some of the most recognisable pieces throughout the art world, are highly valuable and frequently discussed (Christie’s recently sold one of Lichtenstein’s paintings for $56.1 million). In this highly publicised and popular retrospective, the Tate Modern have wonderfully captured the energy of Lichtenstein’s work. By displaying his most famous and lesser known pieces, they have successfully replaced the ‘Lichtenstein: Pop Artist’ tag with the much more appropriate ‘Lichtenstein: Artist’ tag in many causal attendees of the exhibit. It’s a subtle and for some insignificant change, but importantly recognises the breadth Lichtenstein's work.

The first thing to mention about this retrospective is the size of it. Spread over 13 of the Tate’s huge gallery spaces, the exhibition’s range from Lichtenstein’s early brushstroke studies to his late nudes present an artist constantly playing with ideas and experimenting with ‘high’ and ‘low’ art. One of the most enjoyable elements of the exhibition was seeing Lichtenstein’s drawings and planning pages. The detail in these little drawings is remarkable and they attest to Lichtenstein's eye for detail. Look Mickey, one of Lichtenstein’s ‘Early Pop’ paintings, was complimented by the small drawing that was placed to the left of the huge canvas. The canvas displays Donald Duck fishing with the dialogue box: ‘Look Mickey, I’ve hooked a big one!!’. Mickey looks on laughing as what Donald has really ‘hooked’ is the back of his shorts. The planning drawing is noteworthy because it highlights Lichtenstein’s colour and size choices. Using the same yellow for the decking and the sky, he distorts reality, a signal for the distorted reality of popular American image. Lichtenstein was far from a mere imitator or artist of misappropriation. He experimented with the craft of painting and importantly questioned the world around him: a world of surface, a world lacking depth.

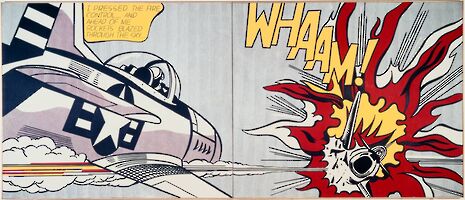

Talking of the curation of the pieces, the ‘War and Romance’ room was especially successful, with horizontally placed canvases throughout the space gesturing to their comic book origin. The juxtaposition of ‘War’ and ‘Romance’, moving from Whaam! to one of Lichtenstein’s distressed women emphasised both sets of pieces' emotionally charged but seemingly recklessness, melodramatic and superficial images. High above the canvases were sculptures that I’d never seen before whose three dimensionality acted as an interesting juxtaposition to the affectedly two dimensional comic book style of the adjacent pieces.

When I think of Lichtenstein, I think of Whaam!. Whaam! is a true Lichtenstein masterpiece showing a fighter jet attacking another jet. Using two canvas boards in the work, Lichtenstein pays homage to his comic book source but subtly changes the colour scheme, speech bubble, explosion and ‘Whaam!’ text to make it his own. ‘Whaam!’ becomes a euphemism, masking the real violence depicted in the image and simultaneously drawing our attention to its dramatic consequences.

Lichtenstein's 'Late Nudes' are particularly interesting examples that highlight his modification process. In these studies, Lichtenstein took his sources and literally undressed them for the canvas. The links from these studies to his wider message are crucial. Rather than being a part of the popular group or creating the popular image, Lichtenstein undresses the image, revealing the flaws and inconsistencies that society tries to hide. On top of that, Lichtenstein’s work constantly questions what painting can achieve and how its role changes in society. The Tate Modern have done an excellent job with this retrospective. When future Lichtenstein’s exhibitions are held, I wouldn’t be surprised if this exhibition is used as a benchmark for quality. It certainly deserves the praise.

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025