Beyond the words: poetry or pop?

Jarvis Cocker talks to Rory Williamson and Madeleine Morley about the mystery of songs

Watching Jarvis Cocker sneak onto the stage of a brightly lit, austere Cambridge lecture theatre was naturally an experience riddled with incongruities. He looked as though he had fallen out of our collective imagination from his iconic days with Pulp (the specs, the hair, the suit, the brogues, the flop, the twang) still every inch the unlikely, outsider rock star. Yet here he was in Cambridge, of all places, not so much out of place but rather bemused by the place, with the objective of the evening proving his status as a poet rather than simply a lyricist.

'Back stage' (actually a lecturer’s prep room) we sit with Cocker for a few fragmented moments to talk about poets and pop. The transformation from pop star to pop poet is a change he resolutely denies, with his humility providing a marked contrast to the analytical scrutiny his songs can be exposed to in the lecture hall. With his trademark sardonic humour he begins by claiming that, in many cases, "words don't matter in songs," pointing to the nonsensical lyrics to the classic 50s rock song 'Louie Louie.' Writing lyrics was never something he wanted to do; it was merely necessary, the irritating side of being the singer of a band.

Part of this modesty is disingenuous, of course: later, he jokes that having his lyrics published didn't change the way he viewed them, "because I always thought they were alright, I'm a bighead. Having said that lyrics aren't important, they've obviously been important to me as I've spent my life writing them." Not only have his lyrics consumed large parts of his life, they also act as a record of it: "this book is the closest thing I have to a life story, or a diary."

Although he admits to the autobiographical nature of many of his lyrics, Cocker maintains that there must always be "an element of mystery to songwriting, otherwise it's boring.” Part of the effort to categorise his lyrics as poetry seems to be energised by the same analytical force fostered by academia, which arguably detracts from some of the "mystery" he seems to find exciting. Indeed, discussing his obsession with writing about mundane details, Cocker claims that a large part of why he writes is to fix these seemingly insignificant things in time, to record them rather than to pick them apart; fundamentally, he says, "I hate change."

The account he gives of his songwriting process certainly defies fixed analysis: an earlier method consisted of "leaving all the writing 'til the last minute. In a blind panic, I'd get all my notebooks out and get really drunk and try to write them all in one night." This meant that he does not even recollect writing the harrowing Pulp track, 'This is Hardcore': "all I had was the title. I left that one until the end when I was completely blind drunk, so I don't remember having written it at all. I woke up in the morning and saw these words and thought 'oh, where did that come from?'

"Sometimes things come from a place that you're not conscious of getting them from; you have to take into account the fact that a lot of what's making it work is something outside of the words." This may not be a fixed, formal Cambridge vision of writing, but it's very Cocker: he's light-hearted and amiable throughout our chat, but never detached. These songs may have come from nowhere, but there is certainly something profound at work.

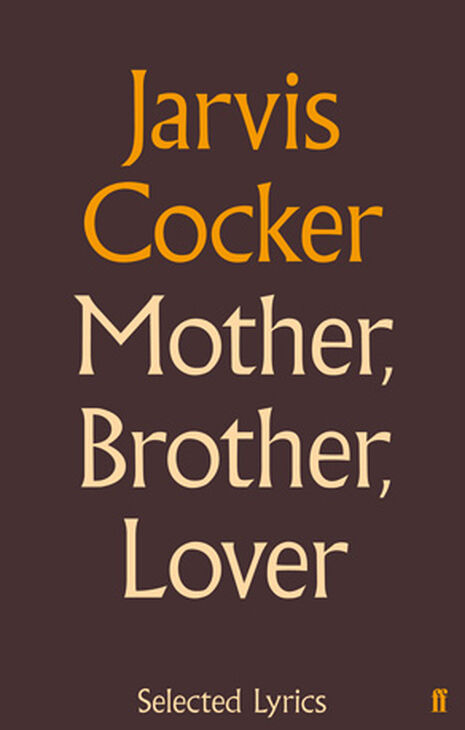

Self-deprecating jokes about returning from Cambridge "with a scarf on, very poetic" rub up against the fact that his lyrics were published by the renowned Faber, "with a proper Faber cover, not a cover with my face on it. I was very adamant about that: I wanted to present it as plainly as possible."

In this unassuming presentation, there is an honesty that is far more profound than any self-consciously poetic lyricism: "when people arrange their lyrics sheets so that it looks nice and poetic, that's when you get really bad stuff produced. When pop music or rock music starts to think it's poetic, that's usually when it really isn't at all. There are certain writers who write pop lyrics that can achieve the status of poetry, but not when they try too hard to do that."

Ultimately, that's what a lot of the discussion trying to position Cocker's lyrics as poetry seems to be: trying too hard to categorise something that should perhaps maintain some of its mystery. Despite any meticulous attempts to dissect them, to analyse their form, to elevate them, or demote them, their effect remains, in Cocker's terms, "something outside of the words": delightful, articulate snapshots of life's little and not so little mysteries to be savoured, not dissected.

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026 Arts / Fact-checking R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis13 January 2026

Arts / Fact-checking R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis13 January 2026 News / SU sabbs join calls condemning Israeli attack on West Bank university13 January 2026

News / SU sabbs join calls condemning Israeli attack on West Bank university13 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026 News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026

News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026