Classical Movements for the Uninitiated: Impressionism

Varsity classical music critic, Alice Rudge, provides an accessible introduction to the world of classical music. First up, Impressionism

Once described as ‘one of the most dangerous enemies of truth in art,’ Impressionism was thought of by many as a vague, wishy-washy mess, a movement that totally disregarded accuracy, line and form. To the Impressionists themselves, however, this new music was dreamy, sensual, imaginative and sought to convey – in the words of Debussy – ‘the mysterious correspondences between Nature and the Imagination.’

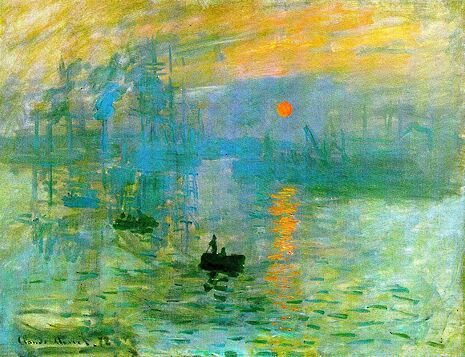

The term Impressionism had already been applied to art, where it was first used as an insult to mock Monet’s 1873 painting Impression, Sunrise. It was then later used by the Academie des Beaux Arts to mock Debussy’s Printemps – so perhaps it is no wonder that Debussy, the father of musical Impressionism, hated that word!

As you can probably guess, the movement in art and the movement in music are closely connected. Impressionists of both art and music looked upon the world as a series of fleeting moments to be captured, not as accurately as possible, but as colourfully as possible. Rather than recreating the object or experience itself, they wanted to recreate the feeling or mood that that object evoked. Subject and object were drawn closer and closer together to create vivid, colourful worlds of mystery and dreams, usually based on depictions of nature or myths.

The movement emerged in France, predominantly in the music of Claude Debussy, who was closely followed by Maurice Ravel to form the dynamic duo of Impressionism. Others followed in their footsteps (Chabrier and Delius among others), and many composers were influenced by their works, but it was primarily these two men who created the main body of works that we now call Impressionism.

Whilst the era that preceded Impressionism was characterised by strong emotions that were created by leading dissonances, Impressionists found new ways to use dissonances that focused on sonority rather than function. Interesting resonances became more important than tension. For example if we compare the opening chords from Wagner’s opera, Tristan und Isolde with Ravel’s ballet, Daphnis et Chloe, this can be clearly heard. Wagner, who was the antithesis of everything the Impressionists wanted to achieve, uses a yearning melody and the famous Tristan chord, which sets up tensions that beg to be somehow resolved. Ravel on the other hand slowly builds up a chord built entirely on perfect 5ths which sets up mesmerising and highly colourful sonorities – it sounds almost as if the orchestra is tuning up before starting!

Aside from the obvious influences of nature, Debussy and the Impressionists thought of themselves as sort of sonic adventurers in their use of the exotic – Debussy famously heard a Javanese Gamelan whilst in Paris and the pentatonic sonorities and hypnotic circling melodies of this Indonesian music can be heard in Pagodes, the first movement of Estampes, a set of pieces for piano.

The Top Five: Impressionist pieces not to be missed

· Debussy – La Cathédrale Engloutie from Book 1 of his Preludes: tells the story of a mythical cathdral that has been submerged by the ocean rising up whilst ghostly bells toll and choirs sing from under the sea. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NsdIkUSjXv8 - Video of Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli playing La Cathedrale Engloutie.

· Debussy – La Vent dans la Plaine: also from Book 1 of his Preludes. Depicts wind rushing across the plains with semiquavers that the player is instructed to play as fast as possible!

· Debussy – Reflets dans L’Eau from his Images: playful sonorities and rhythms create the impression of rays of light gleaming on running water. Compare with...

· Ravel – Jeux d’Eau: on a similar theme to the above!

· Debussy – Prelude a l’apres-midi d’un faune: a symphonic poem inspired by the poem of the same name by the French poet Mallarme.

If you like Impressionism then have a listen to Vaughan Williams, Delius and Messiaen, who were all greatly influenced by the movement.

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025