Bedroom Art: an introduction

In her first weekly column, Ruby Reding introduces us to the personal, cultural and social status of the bedroom

I have thought about bedrooms for years, in separate and singular forms. I have thought about my experiences of moving around so much as a child, and feeling that no space will ever feel like home to me – only people, feelings and smells can. I have thought about the bedroom as a place to retreat and to spend hours every day on the internet as a young teenager.

I have thought about my best and oldest friend’s bedroom – how close to it I feel, how it is the most familiar space I know – and the giant love heart I drew in biro on her wall that enraged her mother. I have thought about the bedroom as a place for crying, for sex, for being ill, for ‘essay crises’, for getting ready for another standard Cambridge night and for watching the Gilmore Girls revival on Netflix and not moving once.

I have thought about the reclamation of space and reaffirmation of identity that comes with having a brand new bedroom at university – one that is entirely my own in a way that it could never be with my family. With the blank canvas of a university bedroom there is the possibility to really claim this space, to personalise it in a new way – without the leftover scraps from early adolescence – those John Green books and Shout magazines.

In my strange Emily Dickinson phase I thought about her tiny body in that tiny space where she wrote about 1,800 poems. (See its overly pristine restoration here). In a more political and cultural sense, private space has always played an integral role in women’s creativity, affirmed so classically and brilliantly by Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own.

“Private space has always played an integral role in women’s creativity”

It has also been a device to trap women and to domesticate them. Betty Friedan’s The Problem That Has No Name was written in 1963 about the oppression faced by housewives in the US. When I first read it at the tender age of 16, it made me guilty for loving cooking, and also angry at how fuelled it is by white-feminism, but for the 1960s it makes a pretty radical and momentous point about sexism and the confinements of private space.

In all of this, I think there is something transcendent about the bedroom as a representation of the most private sphere, as something inherently political, radical and common – a place to escape or empower.

In contemporary art, the bedroom has been used as an entity to draw together the personal and public spheres, to evolve a commonality between women. One of the most well known examples of this is Tracey Emin’s 1998 installation ‘My Bed’ displayed at the Tate Gallery. Though Emin’s personal politics do not extend to the same sentiments, her work no doubt epitomises the idea of the bedroom as a radicalised, female space, where the artist’s mess and sex life is exposed and the private is pushed into the public gallery space. Transforming the bedroom into an art installation represents the modern intersections between the private and public, and speaks up about the need to recognise that the personal is still political.

A new media exploration of the bedroom in art can be seen in works by Molly Soda, who started out as a Tumblr sensation on the internet with a ‘kawaii’ gothic aesthetic that tween fan girls like me swooned over. Now she has had solo exhibitions in London – the first of which is titled From My Bedroom to Yours. The gallery space is transformed into a nostalgic cyber bedroom, in which everything is pink and the webcam videos of her have a familiar and uncomfortable eye contact, forcibly imposing intimacy upon the viewer. It’s this kind of intimacy and isolation that I think shapes what the bedroom stands for.

Another new media and video artist is May Waver, whose digital work includes ‘embedded lullabies’, which is described as ‘the answer to this digital age of isolation’. The rolling bed sheets that move like waves away from the screen seem to transform the bed into a faux desktop background, encapsulating the merging of physical and digital space, of art that can be created in the bedroom and about the bedroom.

In this column I want to explore how the internet has changed the concept of the bedroom and the discourse about the intersection between private and public spaces. Is it a more lonely space? Is it a more connected space? Is it more self-reflective, less or more creative? It remains an intimate space, and art about the bedroom unavoidably shares something personal, or tries to interrogate the idea of the personal. Being a shared experience, can the bedroom be seen as an interconnected and transient concept?

If we look at J.M.W. Turner’s nineteenth-century paintings, including pieces titled A Bedroom: A Figure in Bed – we see that both revel in and resist revealing privacy. The curtains and coveted bodies under sheets have an awareness of the viewer’s eye, a sense that this space is being exposed but at the same time doesn’t want to be. More contemporary examples of ‘the bedroom’ in art work differently to this – the bedroom is dragged physically into the gallery space as an installation, enveloping onlookers. We no longer look onto art; we are invited to be inside it and experience it. Perhaps art about the bedroom is now even more exposed and willing to share, to show, to look into itself. Perhaps it is also all the more isolated and lonely.

“Perhaps art about the bedroom is now even more exposed and willing to share, to show, to look into itself”

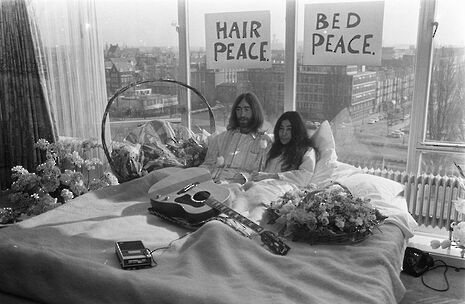

So here I want to think about the bedroom as a collective and common entity, one that is potentially relatable and political. I want to think about how contemporary art has the potential to use the bedroom to make feminist statements and statements about peace and love and loneliness. In an age where the most political activism the majority of us probably did today was sign a 38 Degrees online petition in bed, maybe Yoko and John had it down in thinking about the bedroom as a space to make art and spark activism

News / Christ’s announces toned-down ‘soirée’ in place of May Ball3 February 2026

News / Christ’s announces toned-down ‘soirée’ in place of May Ball3 February 2026 News / Deborah Prentice overtaken as highest-paid Russell Group VC2 February 2026

News / Deborah Prentice overtaken as highest-paid Russell Group VC2 February 2026 Fashion / A guide to Cambridge’s second-hand scene2 February 2026

Fashion / A guide to Cambridge’s second-hand scene2 February 2026 News / SU votes unanimously to support community kitchen4 February 2026

News / SU votes unanimously to support community kitchen4 February 2026 Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026