Andrew Tift

spends a day talking inspiration and reluctant photo-realism with the prize-winning painter and photographer

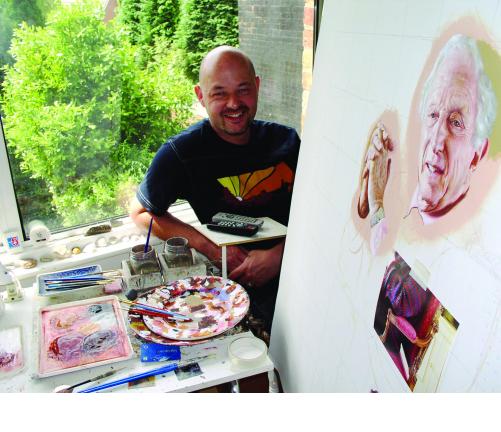

After speaking to Andrew Tift for a matter of minutes, it becomes clear that he is one of those rare people who would be happy to chat with absolutely anyone. Interested and interesting, once he starts talking there’s no stopping him – moments into our conversation he suddenly pulls himself up short, asking in a concerned voice, “Are you getting all this? I know how I rattle through things, so just let me know if you need me to slow down.” Then he’s off again, talking with infectious ease and enthusiasm about his painting and the people he paints.

His portraits are a little like his way of conversing: direct, to the point, pared of all pretensions

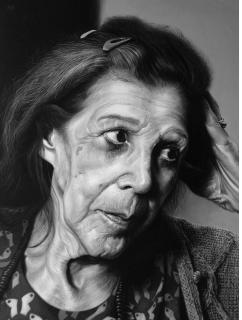

Fittingly, the piece which finally won him the National Portrait Prize in 2006 evolved from a good old natter. In his triptych of Kitty Godley, the daughter of Jacob Epstein and former wife of Lucian Freud, he “wanted to catch the experience of conversation with someone, the feeling of being face to face. In the middle image you can see her visibly thinking about what she’s going to say next – I’m interested in how people receive and absorb information when talking.”

Fittingly, the piece which finally won him the National Portrait Prize in 2006 evolved from a good old natter. In his triptych of Kitty Godley, the daughter of Jacob Epstein and former wife of Lucian Freud, he “wanted to catch the experience of conversation with someone, the feeling of being face to face. In the middle image you can see her visibly thinking about what she’s going to say next – I’m interested in how people receive and absorb information when talking.”

His portraits are a little like his way of conversing: direct, to the point, pared of all pretensions. “I’m not really interested in exposing the soul of the sitter in my paintings. A lot of artists who paint portraits get swept up in this big romantic notion and wrap themselves up in semantics. I’m purely about the physical: I want to capture as objective a likeness as possible.” This objectivity is achieved through the conversation which he so delights in. “What I enjoy most is going and spending time with people. When I was doing my MA I went around West Midland steel foundries and painted pictures of the steel workers. I got to know them really well, and fourteen years later I’m still in touch with them.”

His portraits are a little like his way of conversing: direct, to the point, pared of all pretensions. “I’m not really interested in exposing the soul of the sitter in my paintings. A lot of artists who paint portraits get swept up in this big romantic notion and wrap themselves up in semantics. I’m purely about the physical: I want to capture as objective a likeness as possible.” This objectivity is achieved through the conversation which he so delights in. “What I enjoy most is going and spending time with people. When I was doing my MA I went around West Midland steel foundries and painted pictures of the steel workers. I got to know them really well, and fourteen years later I’m still in touch with them.”

The steel workers aren’t the only ones who have fallen for Tift’s no-nonsense charm – when painting Tony Benn the two “built up a great rapport – he still phones me to see how I’m doing.” These relationships are a testament to the sympathetic intimacy his portraits achieve. I ask him if anyone have ever refused his request to paint their portrait, but Tift is clearly an artist who inspires trust. “I’ve never had a problem with anybody, anybody at all. It’s all about establishing confidence – you’ve just got to talk to people.” At one point in our conversation, Tift describes himself as being “almost like Parkinson”, and it’s not a bad comparison. After a brief phone call, it’s easy to understand why people from car manufacturers in Japan, to Vietnam veterans and cowboys in New Mexico, have all opened their homes and themselves up to this man.

Together with conversation, “narrative objects” are a key element of Tift’s portraiture. He is obsessed with “the things that people collect during their lifetime. They reflect and reinforce the individual’s identity.” His portraits bristle with personal odds and ends. “When I painted Tony Benn it was great – we did the portrait in his house in Notting Hill where he was surrounded by all his knickknacks. Everything in that picture has a story… on the mantelpiece is a pair of RAF wings that belonged to his brother who died in the war.” It is this link with memory that makes objects so important for Tift. He describes how after the death of his grandparents he helped sort through their belongings: “we went through all the objects that they left behind, old combs and little things like that, and even though they’d gone the objects were still there, and with them all the memories that went with them.”

This attention to detail is reflected in the execution of his paintings. Although he hesitates to class himself as a photorealist, he acknowledges parallels with the style, and particularly with artists such as Chuck Close. The photographic quality of his style is strongest in the triptych of Kitty Godley. In painting her, Tift wanted to achieve the effect of “the black and white camerawork on old TV interview shows – when the camera goes right up to the face and scrutinizes the flesh.” Despite this, Tift is a painter first and photographer second. “I use photography as a sketchbook. It can be incredibly useful, especially in the case of sitters such as Lord Woolf, who don’t have much time on their hands.” On being questioned as to the difference between paint and photography, he agrees that the time and concentration demanded by his precision painting fosters the intimacy with the sitter he desires to achieve. But it’s also that paint is simply the medium for him. “People are always saying that painting is dead, but it’s not going to go away so easily. It’s such a natural, instinctive thing to do – think of cavemen and wall paintings.”

Tift, for one, always has his mind bent on the next image he will paint. “When I’m walking around, I always carry a camera. I’m thinking visually all the time, when I’m watching TV, reading the newspaper, doing my shopping, whatever, I’m always looking for possible pictures.” It takes a while for the initial ideas collected on these mental sprees to reach the canvas. He had “loads of ideas”, many of which he knows he’ll “never get round to doing.” There’s a plan to do a series of portraits at Glastonbury, and another of people in old people’s homes. He is fascinated by old people “just think of all their memories and knowledge – everything’s about to be lost... There’s such a sense of frailty to them.”

Tift, for one, always has his mind bent on the next image he will paint. “When I’m walking around, I always carry a camera. I’m thinking visually all the time, when I’m watching TV, reading the newspaper, doing my shopping, whatever, I’m always looking for possible pictures.” It takes a while for the initial ideas collected on these mental sprees to reach the canvas. He had “loads of ideas”, many of which he knows he’ll “never get round to doing.” There’s a plan to do a series of portraits at Glastonbury, and another of people in old people’s homes. He is fascinated by old people “just think of all their memories and knowledge – everything’s about to be lost... There’s such a sense of frailty to them.”

He stresses the importance of letting an idea “ferment for 4-5 months. Because painting is so time-consuming for me, I have to be really sure. I’m not what you could call a spontaneous artist – you could even say I was contrived. But that’s just my way.” The paintings themselves can take anything up to ten months, depending on size. Does he ever tire of portraits? The answer is swift: “No, never. Never, never, never. I can paint fifteen portraits and then start a landscape, but before I’ve even finished the landscape I want to go back to portraits again.”

Tift has been able to support himself with his art ever since graduating. He refers to himself as “lucky”, but it’s difficult not to feel that his honesty, with his sitters and himself, has deservedly got him where he is today. “You’ve got to be true to yourself. Keep it real, as Noel Gallagher would say,” he laughs. “I think students often feel obliged to do installation art or conceptual art, as if they’ve been told that that’s where the best art comes from.” Tift’s career may have run parallel to the ups and downs of the Emins and Hirsts, but he has “always worked very much on my own.” Artistic influences, briefly mentioned, are Van Eke and Holbein, and he speaks admiringly of Hockney and Freud. At the end of the day, however, Tift is all about “painting one person, their memories and thoughts floating around them.” If he’s almost Parkinson, his paintings are indeed “almost like interviews. That’s when painting really gets interesting.”

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025