Rihanna and Artemis: classical casts meet contemporary art at RECASTING

Jade Cuttle explores the current exhibition at the Faculty of Classics, which playfully explores the relationship between antiquity and contemporary art

As an arts student fascinated by the avant-garde, classical sculptures are usually only striking for me when ravaged by time. I see their surfaces as charming only when they’ve been clawed with cracks - when they cradle a cobweb or two. I fall in love with their fractured shapes only when flimsy wires link the limbless stumps of stone back to body, suspended and flailing mid-air. It flaunts the fragility of the flesh. If I’m tempted to steal a silent photograph among classical artefacts, it is when enthralled by the emptiness of a grasp, its fingers having fallen away. In every artistic encounter, I rummage for rupture with expectations.

The Museum of Classical Archaeology, established in the late nineteenth century and run by the Faculty of Classics, might seem like the last place to seek out such rupture. Its expansive collection encompasses more than six hundred plaster casts of Greek and Roman sculpture, including Victorian-era replicas of many iconic works of classical art such as the Parthenon Marbles, Farnese Hercules, and Belvedere Torso. Yet seekers of artistic rupture are to be pleasantly surprised. RECASTING is a contemporary art exhibition, scattered as a series of artistic interventions among the antique plaster casts on permanent view at the Museum. It boldly challenges the classical artistic tradition. Through a curious mélange of materials, mediums and manner, including painting, sculpture, installation, video, and drawing, the works respond to and recast classical heritage in a playful and subversive fashion.

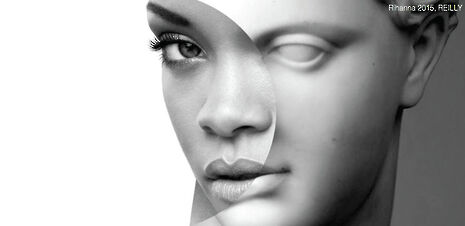

Each piece weaves a new historical narrative that is played out by new characters. In Rihanna (2015) by Reilly, Scottish-born artist and fashion designer whose work has featured for the likes of Gucci, Vogue, Coca Cola and Sony, the pop-star’s cheekbones are chiselled and photoshopped to perfection in pairing with Artemis, Greek goddess of chastity, purity and virginity. The common knowledge held for this deity, hovering like a halo above her innocent head, is suddenly tainted by transformation into a modern-day sex symbol. It is shocking and surprising until we recall those haunting stories of slaughter regarding Niobe's children. The artwork therefore “recalibrates” our understanding of this narrative. “Recasting her as Rihanna promotes her sexuality, reminding us that she was also a hunter of men”. In short, the composite image drags out aspects from the ancient narrative while simultaneously drawing upon the contemporary one, sparking an exciting dialogue between the two that deserves to be heard.

As modern pop stars are merged with classical gods, also including Michael Jackson, King of Pop, there is undeniably an undercurrent message. It takes its root in the fact that, back in antiquity, gods were regarded as celebrities, obsessed with youth, memorialisation, and preserving an aspect of themselves that would live forever. The celebratory idolisation that spans across contemporary media is not such a distant similarity, infused with an obsession for immortality and self-construction. These are the key notes played out in the pieces. It gives us a new insight into how the classical past can be “relevant”, being the driving narrative for these artworks that aim to “reveal some of the contrasts and continuities that define art’s ongoing relationship with the classical past”.

The tangled threads of flesh in ‘Laocoon’ (2014) recast one of the most celebrated sculptures of antiquity. The original piece depicts the Trojan priest and his sons wrestling with sea snakes. However, the heads of the three figures here are replaced by smooth specimens of coloured rocks. It is “a humorous play with the materiality of sculpture” since such paradigms of grace and beauty do indeed descend from raw stone. It is also a “play on sculptural miniatures” that harks back to a long history of small-scale boutique replicas for desk-tops, produced in precious materials, but “witty and ironic” since sculpture heads are traditionally the place for projecting tragic agony.Here it has been disguised by an abstract chunk of rock. The grasp of these figures as their arms snatch at the sky is therefore more than appropriate for an artwork that refuses to remain still, but rather, is forever shifting within the historical narrative of time within which it is embedded, shaping and reshaping its structures. This is encapsulated perfectly when the statue is seen to stand against a strip of high-gloss wrapping paper, as if newly unboxed in a world where classical art is forever invented anew.

The exhibition is a combination of PhD research interests, curated by Ruth Allen and James Cahill who are graduate researchers in the Faculty of Classics. Ruth is a Roman art historian, currently working on the iconography of engraved Roman gemstones. James’s research focuses on the relationship between contemporary visual art and Graeco-Roman art and mythology. Their project will draw to a close this Saturday 15th October, so you best be quick to catch it.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025