Varsity Introducing: Nineb Lamassu

Joanna Taylor speaks to the poet and PhD candidate at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies

Why did you have to flee from Iraq and where did you live afterwards?

I was born into an Assyrian family in Kirkuk, in the north of Iraq. Throughout the history of the modern state of Iraq, Assyrians have been persecuted as the indigenous people and so my family found itself obliged to flee when I was seven years old: my father was actually arrested for being a political activist. It took us about 10 days, walking day and night in the mountains, until we made it to Iran, where we lived in refugee camps. After that we were granted refugee status in New Zealand, and then we moved to Australia. My grandfather was a technocrat employed by the British and when this ended, he was offered citizenship in Australia. I married in Australia and moved to the UK at the end of 2000. I then lived in London, and for the last three or four years, in Cambridge.

What have you been working on in the UK?

After completing degrees at SOAS and UCL, I did an MPhil in Cambridge on Modern Assyrian. I am now a PhD student working on the documentation of one of the Assyrian dialects which is an endangered language according to UNESCO: working to document it is what I am doing with my PhD. I am also employed by the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies as a research assistant.

Do you think the presentation of the Syrian refugee crisis by the Western media has been fair?

I wouldn’t go to fair or unfair, but I would start with terminology. Calling these people migrants is wrong. There is a difference between a migrant and a refugee. For example: a well-to-do British person who does not like British weather and goes to buy a house in Portugal is a migrant. Somebody whose entire house, neighbourhood, city, has been demolished to rubble, who has to flee for his or her life to secure a reasonable future for their offspring, is not a migrant. They are a refugee.

I think the British public in general feel sympathetic about what has been happening but unfortunately the rhetoric has been hijacked by opportunist politicians to instill fear, that ‘they are coming to take our jobs’ and ‘coming to take our land’, but if we look through history, every time there has been a mass migration to a country, it has led to the enrichment of that country. If it wasn’t for migration, we wouldn’t have this beautiful mosaic of cuisines – we wouldn’t have the word ‘bungalow’ or ‘pyjamas’ – so migration has always benefited the host country. But they have to find a way of integrating these waves of populations instead of side-lining them, because that is where the fear lies. We should not fear these people: they are not ISIS, they are fleeing ISIS. We should be careful, maybe, that is natural, but we should embrace these people and help them to integrate.

What are some of the broad themes and ideas behind your poetry?

There is a school of thought which says that if you read a poem, the poet should not be in it: I respect that, but I am not one of those poets. I am my poetry, my poetry is me. For somebody who was born an Assyrian in Iraq, I ‘did not exist’ because of the nationalistic Arab policies. My language was prohibited, so reviving it is very important for me. A longing for something or someone that is gone, lost and cannot be retrieved is also an important theme. I really don’t have a sense of belonging, whether in Iraq or Cambridge, Australia or New Zealand. So what I do is I create that home in my language. Through the process of using my language, I create a mental, abstract space in which I live. Only then do I feel a sense of belonging. I don’t like to use ‘Assyrian’ as an identifier; I’m more comfortable being identified by my language than by my ethnicity, because at the bottom line we are all humans. But language to me is important, especially my language, which is endangered. I feel a duty to create – to coin terms in it – in order to fight what is considered its imminent fate.

Why do you translate your poems into English?

Poetry and literature are the means you use to make the cases of certain people and certain languages, and create awareness for them, which is why I translate my poetry. So, for example, if I’m writing about the suffering of Assyrian people, of course I write it in Assyrian because I want to reflect their ordeals and prolong the life of their language. But the Assyrian people already know what is happening to them, so by translating the poetry I have written about them, I can raise the issue with the general public. The Palestinians have some great poets, like Mahmoud Dawish, who achieve greater good for the Palestinian cause than suicide bombers and hijackers because poetry creates friends and solidarity. Translating the works of the Palestinians and Assyrians, or any peoples being persecuted, is therefore very important.

Are they any differences between your poetry when it is written in Assyrian and when it is translated?

Of course. Robert Frost said that “poetry is what gets lost in translation,” and the translations of my poems will never fully match the original text. Wordplay cannot be translated. Accents cannot be transposed either, yet they change meanings. You have to change the writing, but that’s okay because the wording is not as important as the idea, the semantics behind the words.

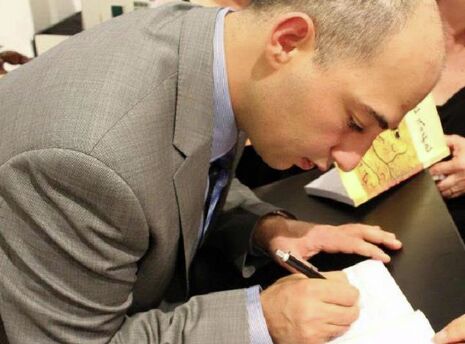

What are your plans beyond your PhD?

I have just released my poetry collection, and I’m actually in the process of doing book-signings around Europe for the small Assyrian community that we have scattered. I’ve got two more publications in type-set. In terms of academic aspirations, I really would like to stay in Cambridge and initiate some kind of lecture series on the modern Assyrian language. That way, we can work towards the preservation and nurturing of the language for generations to come. That would be my ultimate dream.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025