The importance of neutrality

Subjectivity in news reporting is a betrayal of journalism’s fundamental ethical principles

With the commercialisation of the internet and the introduction of new methods of transmitting information, journalism has undergone significant changes in the past decade. News agencies have moved into the hitherto-unfamiliar area of broadcast journalism, broadcasting corporations have embraced the written word, mainstream media has made use of ‘social media’, and the triple threat – the ability to operate on multiple platforms (online, radio, TV) simultaneously – has become a necessity for continued success and audience retention. The internet has also given everyone a voice: we have witnessed the rise of the recreational blogger communicating news to the public; the ordinary citizen promulgating personal opinions on social networking sites; the left or right-leaning online ‘intellectual’ magazine.

In this time of change, it is of the utmost importance that professional journalists think critically before embracing new trends and abandoning traditions. The past year has seen countless heart-breaking developments rooted in ethnic, religious, and political discords, from the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 over Ukraine to brutal and senseless beheadings by ISIS. The emotional significance of these events begs the question of how journalists can manage to continue reporting objectively and whether they even should. How far should we go in embracing new trends? Is it permissible for news reporters, in particular, to introduce subjectivity into their activity?

In my opinion, the answer to these questions is a categorical, non-negotiable “no”. Subjectivity – while perfectly appropriate for editorials, opinion pieces, columns, and blog entries, and occasionally for analyses and features, given that readers are informed that the ideas represented therein are not neutral – has no place in news reporting.

News agencies are not political parties; news reporting is not marketing. Our professional function is not to sell a product, promote a position, teach, preach, or be didactic. Our function is to be informative and truthful. Our duty is to present untarnished facts that allow people to form well-informed opinions. End-users, on the other hand, should cultivate analytical minds and avoid turning to mass media in search of conclusions they should be making themselves.

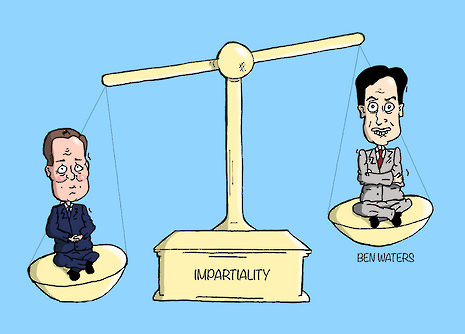

When making a conscious decision to become a journalist, one should be prepared to leave personal convictions at the door and develop the ability to see events through a lens of neutrality, instead of being swayed by background or personal experience. Any alternative approach to news reporting is a betrayal of the fundamental, ethical principles of the profession: impartiality, fairness, and potentially even accuracy.

A journalist has the potential to influence millions of people. The profession can easily be misused to manipulate unsuspecting audiences, as evidenced by the information war in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict. Nevertheless, imposing opinions on others is a breach of free will and failing to provide them with a “complete picture” is a violation of their right to be informed human beings. Consequently, every journalist bears a strict moral responsibility to be impartial. Truly ethical and professional journalism can never have an agenda.

The Reuters Handbook states that journalists must “never identify with any side in an issue, a conflict, or a dispute”; the BBC’s Editorial Guidelines define impartiality as the act of giving “due weight to the many and diverse areas of an argument.” This can be achieved by being open-minded and by representing a wide breadth of opinion in reporting.

Impartiality can be compromised in many ways, even by using non-objective vocabulary. Any one journalist’s failure to be impartial, whether by omitting a main strand of an argument or by engaging in political campaigns outside of working hours, can damage the reputation and legitimacy of an entire news corporation, agency or paper.

Impartiality does not automatically mean that all perspectives must be covered in equal proportion. The BBC, for instance, encourages its journalists to achieve ‘due weight’, which means that “minority views should not necessarily be given equal weight to the prevailing consensus.” Reuters takes a similar position, stating: “the perpetrator of an atrocity or the leader of a fringe political group arguably warrants less space than the victims or mainstream political parties.”

Additionally, it is crucial to note that impartiality does not mean that a journalist must be detached from the ‘truths’ that we, as humans, have come to accept as self-evident: ethical values, systematised understandings of right and wrong, or more philosophical concepts like justice, freedom, and equality. These ‘truths’, though appearing in religious and political discourse, are fundamentally secular and apolitical, and neutrality should not come at their expense. For instance, the majority of humans are likely to agree that terrorism is immoral, so when reporting on terrorism, it would be perfectly acceptable for a journalist to express disapproval even when producing a balanced report.

Violating impartiality can also potentially compromise accuracy. Journalists must never knowingly mislead their audiences and must make an effort to pursue the truth. You might be wondering how anyone can determine what the truth is. The beauty of ethical journalism is that ‘the truth’ (i.e. the well-balanced picture reflective of reality) often appears in the course of the investigative process.

Audiences count on us to do our jobs properly and to be transparent. Real journalism offers a solution to the uncontrolled, informational chaos plaguing the internet. Our accuracy and analysis separate us from rumour-mongers and sensationalists. Our objectivity separates us from propagandists.

It is only if we maintain our ethical principles that journalism will remain a noble profession and a beacon of hope.

News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026

News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026 Interviews / Lord Leggatt on becoming a Supreme Court Justice21 January 2026

Interviews / Lord Leggatt on becoming a Supreme Court Justice21 January 2026 News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 Comment / How Cambridge Made Me Lose My Faith26 January 2026

Comment / How Cambridge Made Me Lose My Faith26 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026