Dictionaries: chroniclers or arbiters?

Lewis Wynn discusses the relationship between dictionaries and the ways words are actually used

Last month an impassioned speech given in parliament by Julia Gillard, the current Australian Prime Minister, eventually resulted in the Macquarie Dictionary changing its definition of ‘misogyny’ from “hatred of women” to “entrenched prejudice against women”. Gillard accused Tony Abbott, the opposition leader, of sexism, hypocrisy and misogyny. Whilst largely commended, the speech was sadly undermined by the developing side-show surrounding her use of the term ‘misogyny’.

Abbott was ‘defended’ on the grounds of not being a ‘woman hater’ per se, just harbouring an ‘entrenched prejudice’ against women; words fail me. Appeals to the Macquarie Dictionary, the dictionary of Australian English which sets standard usage in courts and schools, were made to justify this ‘defence’.

Whilst I for one fail to see how a campaign against Gillard which made use of posters urging voters to “ditch the witch,” in support of a man who referred to abortion as “the easy way out,” can constitute anything other than misogyny in its strongest sense, the dictionary changed its definition, seeming to support Gillard’s use of the word, essentially conflating the two terms.

Some thought the change excessive, with Opposition MP Fiona Nash offering up this wonderful piece of nonsense in response: “It would seem more logical for the prime minister to refine her vocabulary than for the Macquarie Dictionary to keep changing its definitions every time a politician mangles the English language.”

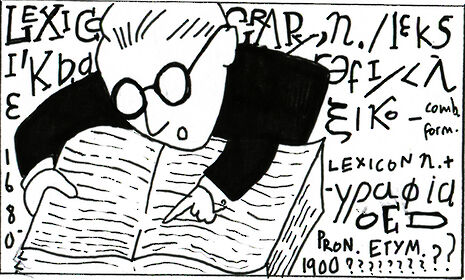

This recent episode illustrates the nebulous and contradictory relationship we have with our dictionaries, the two general and paradoxical approaches we take towards them. On the one hand they are standardisers which should be adhered to in order to ‘make sense’, on the other, a document of a developing and active language, the chronicler of change rather than the arbiter of truth. The pre-eminent Cambridge scholar William Empson once asserted that we “could not use language as we do, and above all we could not use it as babies, unless we were always floating in a general willingness to make sense of it.” This “general willingness” is negated by the mission of publications such as the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, the ‘official moderator’ of the French language, which seek to set in place definitive allowances on word meanings and language use.

The role of etymology and word definitions in relation to questions of self-possession and knowledge has long been a marked feature of Cambridge’s poetic and literary discourses, particularly in the work and influence of J.H. Prynne, the formidable poet who now lives in Cambridge as a Life Fellow at Caius.

Keston Sutherland wrote in his 2004 PhD thesis J.H. Prynne and Philology (supervised by another great Cambridge poet, Professor Simon Jarvis), that the poems which constitute Prynne’s first two collections are all engaged in “the philological investigation of concepts; that is, the investigation of the changing appearance of individual concepts throughout the history of language and considered under the primary aspect of their “names”.’

Yet despite a project which in many ways reflects the concerns and activity of the Oxford English Dictionary, Prynne himself referred to that publication as the “new Oxford dictionary of Etymological Evasion and Cowardice,” particularly unimpressed with its entry on the word ‘winsome,’ and its suggestion that it entered the literary language “(god help us),” from the “(one presumes) non-literary north.” Prynne’s subsequent examination of the English rune ‘wynn’ may have confused my own self-possession with regard to my surname, but I doubt that’s quite the point.

What this does emphasise, however, is the fragility of the pre-suppositions on which a definitive chronicle of words and their usage must necessarily rest, such as the possibility of a ‘literary’ language which regional variations can ‘enter.’ It seems obvious, in light of all this, that a dictionary can only ever really be an account, a history, rather than a guidebook or law. To suggest that somebody should refine their vocabulary rather than a dictionary change its definition is completely at odds with the project of etymology indeed, it would render etymology null.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025