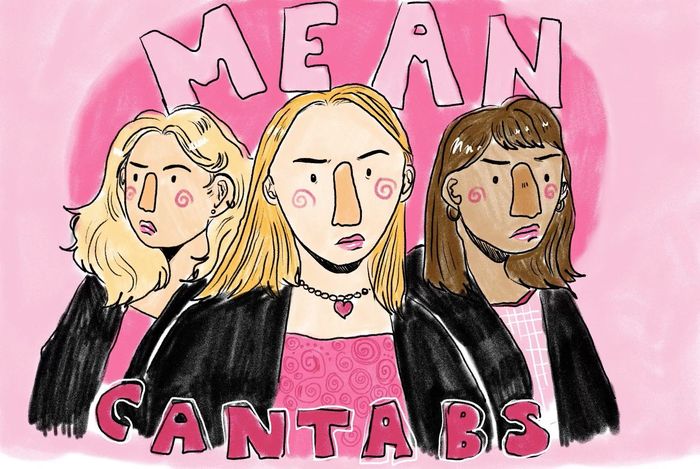

Head to head: tripos rankings

Love them or hate them, they’re one click away on Camsis. Hugh Jones and Maddy Browne argue about whether tripos rankings rank top or bottom for them.

Hugh

If you want to know whether the University ought to tell students how they ranked in their exams, there is only one question you need to ask: “Is that piece of information useful?” For my money, the answer is yes. Marks and degree classification on their own are vague metrics. Knowing whether you were above average in your year is clearly helpful, and students who do really well deserve to know how close they came to topping Tripos. Those who barely scraped a 2.i might be spurred to invest more time in their degrees by seeing how close they came to the bottom.

Of course, the objection isn’t really that rankings don’t matter. The objection is that being told your rank is stressful. I understand this. I was very unhappy at how I did in first year; if you had just told me that I’d got a 2.i then I probably would have spent a lot less time moping in the toilets of the PR firm I was interning at when I got the news.

The important point though, is that I wasn’t sad because I had been told my rank. I was sad because I had done badly, and because I had a serious case of overconfidence. Both of these things – my incompetence and my pride – were my problem, whether I knew it or not. Having my confidence knocked was painful – but it needed knocking.

Not telling students their ranking in case it upsets them is no different from not telling them their marks or their classification. Your ranking is part of your result. If you find it disappointing then you either need to work harder next year, or get a grip and realise that you are never going to top Tripos. Both of these pieces of information are hard to swallow – but that doesn’t mean they aren’t worth knowing.

Maddy

We have our fair share of traditions here at Cambridge. A lot of these are relatively harmless. I can cope with gowns and matriculation and even Latin when it comes with a three course meal. They’re almost cute compared to the rankings system. This goes beyond the archaic when a whole year’s worth of struggle is boiled down to one number.

Admittedly, grades are also one number. However, using grade boundaries creates an assessment of work that is defined against a recognised standard and against mark schemes. These boundaries are something that we and employers will recognise that doesn’t reek of the Oxbridge superiority complex.

Are classmarks not enough? Apparently not if you’re applying for postgraduate funding here. The fact that applications use rankings instead of grades delegitimizes student effort by judging someone on an arbitrary, frankly unnecessary? value, instead of a nationally acknowledged grading system. This seems vastly at odds with the multifaceted and holistic undergraduate criteria, which doesn’t assume that there is a level academic playing field.

The university tells us that we don’t have to look at it. It then puts the ranking a single click away from the result that should matter more. Of course I was going to check it! It taps into the part of my brain which is constantly comparing myself with others, fighting to do well as if that one mark between me and the person above me will make all the difference. If I’m trying to readjust how I measure achievement, then a reductive number is only going to set me back. The university needs to recognise that its cohort of perpetual overachievers are not going to benefit from excessive competition. I’m tired of falling back into bad habits of comparison, habits that this tradition seems intent on exacerbating.

If they are not useful for us, or good for our mental health, then we should no longer tolerate destructive traditions. No amount of candlelit formal dinners can get the university out of this one.

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026