We should be glad to see personal statements go

Frankly, it’s remarkable that it’s taken UCAS this long

The personal statement is designed to be personal and original. The 4,000 character-long essay can take around 30-40 hours to complete for some. I think I must have spent even longer writing mine. But I shouldn’t have bothered: increasingly, tutors, application assistance services, and more recently, AI, all seem to have memorised the manual for success.

Thirty years after its arrival, the personal statement is finally on its way out; earlier this month, UCAS announced that personal statements would be scrapped from the university application procedure, following concerns that it’s “contributing to inequalities in higher education access”. Quite frankly, it’s remarkable that it’s taken them this long.

The role that personal statements play in the admissions process seems to be somewhat of a mystery. UCAS states that each university relies on a “variety” of evidence and indicators to make offers, combining information from the personal statement, references, and previous academic achievement. In reality, however, the admission process does not always consider all of these components as holistically and equally as we may hope.. Back in 2009, for instance, Cambridge’s director of admissions, Geoff Parks, admitted to the Guardian that the university disregards the personal statement from the admissions process.

Universities’ willingness to ignore personal statements may be due to the fact that personal statements are often of a poor quality. The Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) found that 83% of drafts fail to present evidence-based opinion about a relevant academic subject, thus failing to fulfil the role of the personal statement.

Most importantly, the 4,000-character essay falls short in its ability to predict the applicant’s future academic performance, which is the main goal of the application process itself. A recent study examined the statements of 176 UK medical students and tracked their academic performance over a year. The research reviewed a series of categories relating to the personal statement and found no evidence that personal statements were “predictive of future performance”.

“The role personal statements play in the admissions process is something of a mystery”

The personal statement is often hailed for levelling the playing field between applicants, regardless of their educational backgrounds. This could not be further from the truth. Personal statements tip the admissions process in the favour of privately educated students. A report by the Sutton Trust found that “work-related activity” was a “major area of difference” in personal statements, meaning that independent-school applicants were able to list prestigious internships and placements, while those from state schools were left describing school trips and part-time jobs. Another study found a positive correlation between the cultural capital of students and their chances of receiving an offer from Oxford University, even when controlling for prior attainment and other factors.

The conversation around personal statements points to a much wider problem surrounding the lack of transparency and consistency in our university admission system. A study on Oxford University found that university admissions tutors “enjoy room for discretion” in the process, often making decisions that are “not formulaic”.

“Getting rid of personal statements is an opportunity to get more information about each applicant”

Various other studies have unearthed a lack of consistency in how faculty members and admission staff rate personal statements. This is unsurprising, considering that the standard of a personal statement is subjective, and not quantifiable. It’s hard to believe how universities have been basing decisions off them for so many years.

Some have suggested that scrapping personal statements depersonalises the admission process, but in reality, it’s an opportunity to give more information about each applicant. UCAS has proposed a questionnaire to replace personal statements, prompting applicants to answer short questions about relevant experiences and mitigating circumstances. This is similar to the US system, which offers applicants a set of prompts to reflect on, to curb the challenges created by the long-form free-response nature of the personal statement.

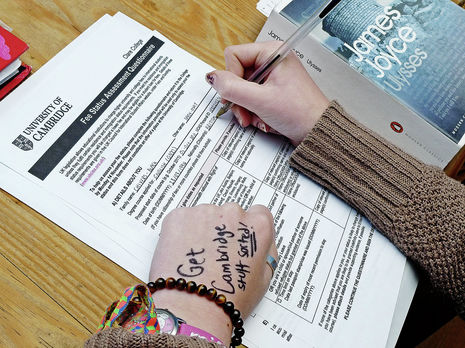

Cambridge University’s own “My Cambridge Application” form also offers a potential framework for reform. Previously known as the SAQ, the form prompts applicants for details regarding class sizes, educational difficulties and support received from their school to provide a more holistic view of each candidate.

The form also provides a space for “anything else you would like us to know?” As someone who had never received my education in English before applying to Cambridge, spaces like these were crucial to give additional contextual information, which I otherwise would not have had the chance to disclose.

Scrapping personal statements is a small, yet overdue step in the right direction. However, it is only the first piece in the much larger jigsaw puzzle of the problems in our current university admission system.

Much like the personal statement favoured the privately educated, so do predicted grades, which continue to form a substantial part of university offers, despite it being estimated that almost 1,000 disadvantaged, high-achieving students have their grades under-predicted each year. If the application process is to truly become a space of equal opportunity, it should acknowledge the unequal circumstances students have faced before, and attempt to actively disarm their effects. This necessary and pressing process requires solutions that are creative, thoroughly researched, and up to date with the times in which we live. We are better without the personal statement, but there is much more that needs to be done.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025

Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025