Gender stereotypes and stigmatisation has catalysed a global epidemic in suicide

Following YouTuber Logan Paul’s widely criticised video about suicide in Japan, Kaia Nisser asks why suicide, particularly amongst men, is so widespread around the world

Logan Paul’s suicide forest video – uploaded to his 15 million YouTube subscribers – has unleashed a torrent of public outrage. Paul claimed that “the reactions you saw on tape were raw, they were unfiltered”; simply serving to highlight the detachment and biases that often belittle the pandemic of suicide. Paul and his peers laughed at the corpse of a man who had hung himself in a Japanese forest notorious for suicide. But this is not merely one self-entitled YouTube star looking for views – his reaction was symptomatic of a generation which perpetuates the stigma of mental health.

Such disengagement is deeply problematic; undeniably, suicide is a social issue that is not limited to one country or continent. Where it is most common in young people, it is universally higher amongst men than it is women. Whilst women are more likely to experience depression, they are also more likely to seek help. Statistically, men are more inclined to self-medicate, leading to alcoholism and addiction. Globally, men are nearly twice as likely to commit suicide than women; in Europe four times more likely.

“It is not national governments that will change such biases, but the people it affects, who need to motivate change; a change that transcends national borders”

In Japan, suicide rates have risen dramatically over the last few decades; it is now the single biggest killer of men aged 20 to 44. Some attribute this to Japanese history of the Samurai and their belief in suicide to maintain honour; in the modern world, it’s a way to accept responsibility. But why then is it rising across so many countries? National history is an insufficient answer.

Japanese psychologist Wataru Nishida blames the high pressure that young people increasingly face. This is exacerbated in a society where talk of mental health is inextricably linked to suicide, which is in itself viewed as taboo. A lack of mental health support has led to a phenomena known in Japan as ‘hikikomori’, where predominantly young men withdraw from social life and confine themselves at home indefinitely, frequently a precursor to suicide. Government figures from 2010 reveal 700,000 people were living as hikikomori; now more recent numbers show up to 1.55 million experiencing such antisocial withdrawals.

But occurrences of hikikomori are not limited to Japan, and have been frequently observed in the United States, Oman, Spain, Italy, South Korea and France. So why is there no name for it outside Japan? Not because it doesn’t happen, but because everywhere else, as in Japan, young men are all too often driven to taking their own lives instead of voicing their suffering beforehand. It is not any one culture perpetuating this situation, but all cultures. A quick look at national rankings of suicide rates will not show Asian countries exclusively leading the rankings, but a geographical mix including South American countries, Europe and Africa. In Russia, for example, teenage suicides are three times the global average. Belgium, India and Poland all have higher suicide rates than Japan. The pertinent question is why is it the same demographic across these countries? This is not an issue of nationality, it is a problem of gender and generation.

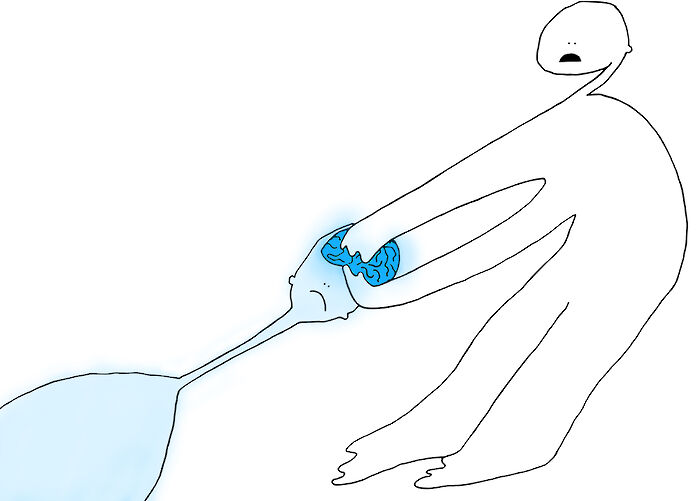

Why are young men more likely to commit suicide than women, regardless of nationality, culture or ethnicity? As everyone is drawn into a global struggle for progress, it seems individual wellbeing is becoming devalued. A lack of empathy in a world obsessed with efficiency and profit becomes apparent. This reality allows such behaviour as that of Paul’s to persist, blinding us to the causes of suicide that have nothing to do with where one lives.

Often it is harmful gender stereotypes which exacerbate this view across all cultures. Men must be macho, invulnerable and unemotional; whilst, inversely, women must be feminine, vulnerable and emotional. The young have inherited such archetypes, whilst struggling to be successful in a highly competitive world, where such outdated paradigms are no longer meaningful. Men are consistently discouraged from seeking help, whilst young people often delegitimize mental health disorders. It is not national governments that will change such biases, but the people it affects, who need to motivate change; a change that transcends national borders. Suicide is widespread and so too should be our response

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026