On Northern Ireland, Theresa May is downright dangerous

May has failed to grasp how Brexit could undo the delicate peace settlement

It’s time to snap back to the present. While the media mulls over Diane Abbott’s comparison of her hairstyle to her views on the IRA in the 1980s, Northern Ireland is in crisis. Concerns over the impact of Brexit, along with the collapse of the government in January have left the peace process as vulnerable as it has been in its 19 year history. This crisis is now, in 2017, and neither source nor solution will be located in 30-year-old soundbites from the current Labour leadership. The fragility of the peace process is a result of a totally insensitive approach from the Conservative government in the past year.

The Northern Irish government collapsed after Arlene Foster, the first minister, was implicated in a disastrous renewable heating scheme that cost the taxpayer £500m. So, the cause was admittedly a local affair, but May’s apparent apathy is actively preventing a solution. The snap election, whether championing democracy or seizing political opportunity, disrupted negotiations intending to return a government. They will have to be resumed after the election, prolonging this period of national paralysis. Moreover, the resumption will now coincide with the unionist summer parades, when sectarian tension runs highest: not an atmosphere conducive to conciliation.

What makes this careless laissez-faire approach more inexplicable is that a speedy resolution is totally in the best interests of the Conservative government. If the stalemate continues, direct rule from Westminster may have to be restored. Not only would that be a huge backwards step in the peace process, but it would be an extremely inconvenient distraction when the government needs to focus on Brexit. The last time devolution broke down, in 2002, it took 5 years to resolve.

“It does not take a genius to infer how far down May’s priority list Ireland lies.”

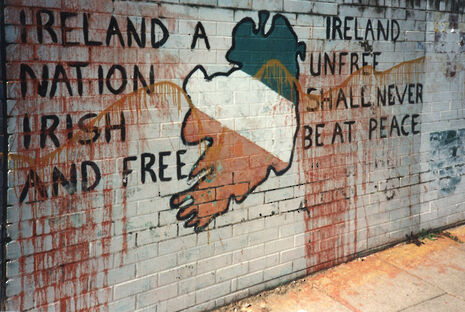

Far more worrying is Northern Ireland’s place, or lack of, in the Brexit negotiations. A hard Brexit implies a hard border somewhere, and with a United Ireland still difficult to imagine in the near future, a hard border between the North and the Republic appears to be the only option. The existing soft border is integral to the peace that has existed since 1998; the free movement it guarantees is a pivotal conciliatory gesture to Irish nationalists.

If the soft border is sacrificed, the nationalist outcry will be severe and the basis for cross party co-operation in Northern Ireland will be difficult to repair. The Irish border is listed as one of the EU’s top 3 priorities going into negotiations. They appreciate the importance of this issue for the stability of the peace process, yet May seems to be more interested in Gibraltar.

If the UK comes out of the European single market, there must be a commitment to a special exception for the Irish border. May’s casual statements about the “good will surrounding the border issue” simply are not good enough at this point. She was ‘too busy’ to accept an invitation to clarify Ireland’s place in Brexit to the Irish parliament, a schedule that could fit in Trump and Erdoğan, the Turkish reactionary. It does not take a genius to infer from these actions just how far down May’s priority list Ireland lies.

Northern Ireland is past the point where a border dispute could wind the clock back to the barricades and street fighting of the 1970s. However, those images remain fresh in the minds of many. Coming to terms with the legacy of the Troubles remains a slow process and does not need border uncertainty to turf up old memories. Northern Ireland’s unionist-nationalist divide lives and breathes in Northern Irish politics, and May is adding fuel to the flames.

Perhaps an overseas population of just 1.8 million doesn’t deserve special treatment, but this still deeply divided society desperately needs sensitivity. What we are seeing now is a level of incompetency that could unwind almost two decades of progress. It can be said with certainty that if Theresa May doesn’t start to take the peace process more seriously, the tensions unleashed will make Northern Ireland start to feel a lot closer to home.

It is probably naïve to think that many in Cambridge will really factor in the crisis and future of Northern Ireland into their decision on 8th June. Still, the blatantly one-sided media coverage in the run up to the election is creating a conception that this relentless ‘strong and stable’ Conservative mantra applies to Northern Ireland as well. It does not. Conservative mismanagement is why Stormont, the home of the Northern Irish assembly, has seen more tourists than politicians through its doors in the past five months. Imagine what another five years could cost

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026