Making a mark: grafitti and immortalising our presence

Having visited France’s cave paintings, Heather Leigh argues graffiti can reveal the unrecorded aspects of ourselves and our society

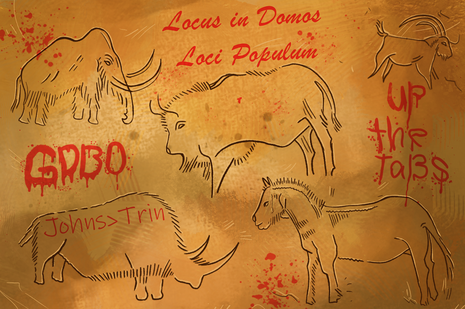

The train rattles ominously as we travel deeper into the cave. It’s cold. It’s dark. A baby begins to cry. I’m devising a last-minute escape-plan when we jolt to a halt, and lamps illuminate walls covered with prehistoric cave art. Mammoths amble across the rocks while bison, horses, and woolly rhinoceroses roam 'the Great Ceiling'. With my neck craned upwards and my mouth hanging open in a deeply unflattering state of awe, I’m struck by how universal our desire to create art is. 16,000 years ago, our ancestors living in 'the Age of the Reindeer' (the cool name for the Magdalenian Era) entered the Rouffignac Cave in France to make their mark. They carved into the rock face with flint, bone and wood, they sketched using manganese dioxide as black pigment. They even made imprints by running their fingers through soft, chemically-altered layers of rock, creating the kind of abstract art you’d expect to find – and pretend to understand – in the Tate Modern today.

“We all want to leave a tangible trace of our existence”

As I admire the prehistoric display, I’m startled by a bison with huge, black letters scrawled on top of it: “BOUTIER 1906”. Such graffiti – made by lines of soot from a candle flame – covers a substantial area of the cave, some of it dating back to the 16th century. The rock here is a mess of marks made by different people from different times. While it’s a shame that parts of the prehistoric art have been disfigured, there’s something strangely beautiful about the way we’re united by the desire to make our mark - a twist on Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am”: “I mark, therefore I am”. Outside, I find some chalk and stoop to write my name on the pavement. We all want to leave a tangible trace of our existence, to prove that we were here, that we mattered. Creation becomes legacy.

Art is an outward manifestation of an individual’s inner world and the society in which that individual operates; it’s clichéd but true. Our values inform our art, and so art doesn’t just reflect values, it becomes a physical embodiment of them. In this way, tracing the changes in humanity’s mark-making habits offers tangible insights into our ancient ancestors’ worldviews. Of the 250 animals displayed inside the Rouffignac Cave, only five are human. We don’t know the exact reason this art was created, but one thing seems clear to me: it bears testament to a biocentric worldview which has been lost in the modern age. Our Magdalenian ancestors understood their place within the wider ecosystem, and were able to view life with a perspective which wasn’t polluted with anthropocentrism. Centuries later, the trend of graffitiing one’s own name stands in stark contrast, marking a shift away from community and towards individualism. And as I look at a rock where animal forms are eradicated by graffitied human names, I am reminded that, just as our obsession with the self and our prioritisation of our own species is reflected on the cave wall, it’s also reflected in our real-life relationships with the natural world.

“Cambridge’s pubs and clubs are covered with scribbles and scrawlings”

I left the cave feeling sombre, but upon entering the female bathroom outside, I’m told “you’re so damn beautiful girl!” by curvy lettering on the cubicle door. It’s not as mammoth as the wall-art I’ve just seen, but it’s a form of mark-making in its own right. In the male bathroom, the boys have taken a different approach, opting for some classic iconography: the timeless cock and balls. Once again, the marks we choose to make reflect certain preoccupations.

Closer to home, Cambridge has a wealth of graffiti to explore. Robert Athol, ex-archivist for Jesus College, conducted a survey from 2016-2018, during which he found 1,076 examples of graffiti dating from the 16th to the 20th century. These included etched names, ritual protection marks, coats of arms, and depictions of various figures. “I enjoyed finding the names of individuals and then matching those names with the archives to discover who they were”, says Robert. He recalls: “A fireplace in one room had the names of two students written closely together. When I went to the college archives to find out who they were, it turned out they were resident in College at the same time and so indicated the likelihood that they were friends and, possibly, roommates.” Students are still marking their territory today – rest assured that my beloved first-year accommodation has my name written under the desk (if you’re a porter reading this, it doesn’t).

“Humans always have and always will make their marks”

Cambridge’s pubs and clubs are equally covered with scribbles and scrawlings, and taking an intellectual interest in the city’s graffiti is the perfect excuse to spend yet another evening in The Eagle. Or you might prefer The Prince Regent, where you can immortalise your Cambridge romance by scratching your partner’s initials into the toilet wall alongside the city’s other lovebirds. And let us not forget the “empathy has it’s limit’s too sometime’s” graffiti that decorated the Hills Road bus stop last Lent, which my drunken self found unimaginably profound as my friend sat down in the bus shelter and asked me to tie her shoelaces for the millionth time post-Revs. (It seems the council’s empathy also reached its limit, as this graffiti has since been scrubbed away.)

Pay attention to what we create: the art we choose to produce and consume reveals a lot about ourselves and our society. Robert agrees: “Graffiti can tell us about […] individuals [and] how they interacted with the built environment around them, but also provide an insight into common superstitious belief, as well as details of personal lives and relationships, evidence of which might not survive anywhere else nor appear in the written record”. One thing is certain, great or small, sacred or mundane, prehistoric cave art or school-desk doodles, humans always have and always will make their marks.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026