Botticelli teaches us to make love, not war

Ailsa McTernan delves into Sandro Botticelli’s irresistible depiction of two young lovers, Venus and Mars, on imminent display at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

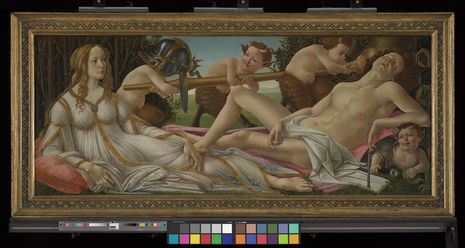

Venus, the goddess of love, lies semi-reclined on the cool spring grass. Her left hand delicately pulls down the semi-translucent frock that has gathered around her thigh. A dreamy gaze falls upon sleeping Mars, his head resting against a tree stump at the opposite end of the panel. One drooped hand falls deftly on his thigh, a suggestive sign of his now recumbent member. His neck cranes backwards into a deep slumber. The male habit of falling asleep after sex was, after all, a popular subject for bawdy jokes at Renaissance weddings.

The viewer has stumbled into an al fresco post-coital scene. the god of war, exhausted from his love-making with the goddess of love, is utterly oblivious to the bacchic mischief of the chubby satyrs around him, despite their best efforts. One blows a conch shell directly into his ear while another traps his finger in a pointed metal instrument. His military regalia have become the innocuous playthings and dress-up attire of the giggling satyrs. Stripped of his soldierly garb, the god of war is rendered incapacitated in the face of passion, whilst the goddess of love appears utterly unaffected by her encounter with the ‘ruthless’ Mars. The message is clear: love always triumphs over war.

“This work was believed to have carried a magical, talismanic power”

The work takes centre stage in the ‘National Treasures’ display at the Fitzwilliam Museum this Spring, which forms part of the National Gallery’s bicentenary celebrations. It brings together a number of other Renaissance works from the Fitzwilliam’s permanent collection to explore ideas of sex, power and the body in art. The historic loan presents a rare opportunity to see the work outside of its permanent home in London.

Painted in around 1485, it is one of Botticelli’s most well-known works, celebrated for its playful yet intimate treatment of the popular theme. The unusual longitudinal panel, besides providing a deliberate snug setting, indicates the painting’s function as a ′spalliera’ panel. According to the sixteenth-century writer and painter Giorgio Vasari, the painting decorated a room in the Vespucci Palace in Florence. The wasps (or vespe in Italian) that encircle Mars’s head suggest a pun on the name of the affluent Florentine family. The myrtle bush behind the figure of Venus, a well-known symbol of matrimony, suggests that this work was commissioned to commemorate a marriage. A likely setting would therefore seem to be a bedroom or ‘camera’, possibly as a backboard for a bench or a chest or inset into the architecture of the wall.

“This candid ‘morning after’ scene would have felt as familiar as When Harry Met Sally... and arguably still does”

Beyond its obvious visual appeal, this work was believed to have carried a magical, talismanic power. The erotic subject was intended to initiate love-making between the young couple while Mars’s beautiful naked body was thought to bring the birth of a male heir. Although some have suggested that Venus’ relatively demure state of dress indicates her purity and chastity, her simultaneous betrothal to Vulcan, god of fire, makes her a questionable standard for fidelity. Her creased skirt and relatable ‘bed hair’ are the tell-tale signs. She is not the shy, modest goddess of love we see in Botticelli’s famous Birth of Venus (c.1485-86), but a self-assured, lascivious young woman here.

This candid ‘morning after’ scene would have felt as familiar as When Harry Met Sally... and arguably still does. To a fifteenth century audience, Botticelli presents a strikingly modern telling of this popular theme. Venus, with her pale skin, blonde hair and rosy lips, denoted the ‘ideal’ Florentine woman. Similarly, Mars’s nudity, although a clear citation of classical statuary (the equally lubricious Barberini Faun comes to mind), sustains none of the marble coldness of its Greco-Roman exemplars; his soft, fleshy body, painstakingly rendered in egg tempera and oil, still appears as palpable over half a millennium later. The informality and tenderness of this scene feels as timeless as the work’s overarching message: make love, not war.

Although we can’t put the work’s alleged aphrodisiacal powers to the test in time for Valentine’s Day, you can catch this romantic masterpiece in the Fitzwilliam’s ‘National Treasures’ display from the 10th May until 10th September 2024.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026 Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026

Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026