Retrospective realities at Wolfson’s new exhibition

Tim Head’s multimedia exhibition ‘How It Is’ picks apart with forensic scrutiny the anxieties of our past and present

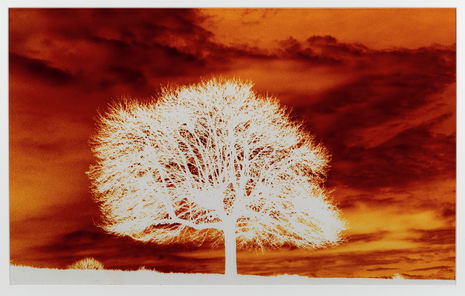

A tree, bone white, stretches slender branches up towards the frame. Its leaves feather out into a ghostly halo, frosting the dark orange cloudscape that brews behind. The tree looks dead, killed off in its meticulous erasure from the shot that leaves only an arboreal echo in its wake. A glance at the accompanying label, branded with the word Winter, is enough to confirm any simmering assumptions. Across the room is its sister, Nuclear Winter, a hanging mass of similarly skeletal branches sprawled across an ink black background.

“Brutally honest about future catastrophism, these pictures say what everyone is thinking”

Tim’s work is starkly real, a stripped back, glaring reflection of the world around us and the threats that cloud its future. This exhibition, How It Is, is a retrospective display of artwork in different media that spans the prominent British artist’s work from the beginning of his career in the 1970’s to now. Staggered across the cream walls of Wolfson College’s Combination Room, his art encompasses painting, photography, and digital work. Deeply concerned by issues such as climate change and nuclear war, Tim’s work targets our creeping anxieties, blows them up into the visual, and offers them up for scrutiny. Brutally honest about future catastrophism, these pictures say what everyone is thinking.

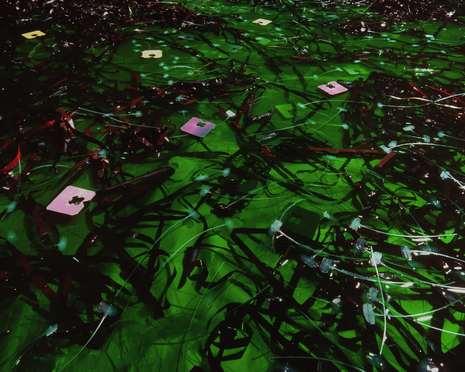

This focus on contemporary concerns is no accident. The curator, Professor Phillip Lindley, wanted the retrospective to pull out a common thread that weaves its way through Tim’s work across the decades, and make a show that resonated with current day students. Tim engaged extensively with the threat of plastic pollution during the late 80’s and early 90’s, a subject matter that Phillip felt would speak immediately to people today. Petrochemicaland 3, at first glance, is a kind of bedraggled lily pond, a shock of green peppered with pale pink. Dark ribbons flow through the water. Pond weeds? Amphibians wriggling their way out from murky depths? The image appears as a mass of swamp-like aliveness, explicitly biological. But take a step closer, and the scene shifts into focus. Lilies morph into pink plastic tags, aquatic foliage reveals itself to be synthetic, a tangled mess of human materials. Before your eyes, the photograph undergoes a metamorphosis into a conglomeration of plastic waste, and its green glow, seemingly a pulsing sign of semiaquatic life, becomes venomous.

A meaningful transformation that comments on the pollution of the planet: we stand watching as nature shifts into human wasteland. There is something unsettling about Tim’s ability to reimagine the familiar and present it in a perturbing new light. His art has an alien, tactile quality to it that is fixating: it makes you squirm, but you can’t stop looking.

“His art has an alien, tactile quality to it that is fixating”

The focus evolves into something more explicitly scientific in his piece Cow Mutations, a study for the painting with which he won the John Moores Painting Prize in 1987. Hung jauntily by the door, this ink on paper piece depicts a mishmash of wobbly, melting cow faces that dribble and droop around each other. The sinister undertones that speak to Tim’s revulsion against factory farming, and his hostility to genetic modification, are softened by the sweetness of the unsuspecting snouts and their quivering bearers; the cows evoke a burst of unexpected empathy that makes their farmyard fate all the more tragic. Similar anxieties are channelled in Exquisite Corpse, a pencil drawing that layers animal bodies- cow, chicken, sheep- over one another, creating a monstrous, shapeshifting embodiment of mass farmed livestock. The overlapping bodies are topped off by a rectangular white cut-out, coffin-esque. A morbid reminder of the effects of the meat and dairy industry, the sketched animal figures are reminiscent of diagrams found in the pages of a GCSE biology textbook, imbued with a distinctly forensic quality that mirrors the scientific interest apparent in his work.

The Combination Room is aptly named for the exhibition; Tim flits between mediums in his effort to represent social and environmental concerns, punctuating photographic work and sketches with digital drawings and watercolours. How It Is may be retrospective, but the feelings of dread that Tim was feeling at the start of his career in the 70’s resonate profoundly with the anxieties many of us are experiencing today. Tim’s work is an unflinching depiction of the reality of things, his art turns the stomach but arrests the gaze; an uneasy emulation of contemporary concerns, and a reminder of the ever-increasing urgency that they demand.

The exhibition is open to the public at weekends from 10.00-17.00 until Sunday 21 January.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026