Processing Touch: ‘Artists Buttons’ at Kettle’s Yard

Eve Connor ponders the social, political and decorative significance of the limited edition sets of buttons created by leading artists in support of Kettle’s Yard

In a letter to his sister, Keats lamented the shortcomings of the written word compared to ‘speaking — one cannot write a wink, or a nod, or a grin [...] One cannot put one’s finger to one’s nose, or yerk ye in the ribs, or lay hold of your button.’ When Lucie Rie couldn’t secure a licence to make pots, she made buttons instead. On both occasions, the button is a substitute: the bridesmaid and never the bride.

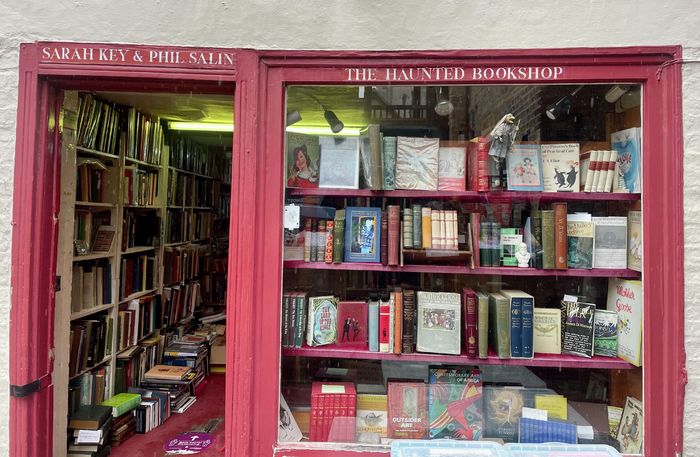

Drawing inspiration from the gallery’s recent Lucie Rie: The Adventure of Pottery exhibition, Artists Buttons challenges this pattern. The project commissioned ten leading artists to craft their own sets of buttons, available until December for purchase from the Kettle’s Yard shop.

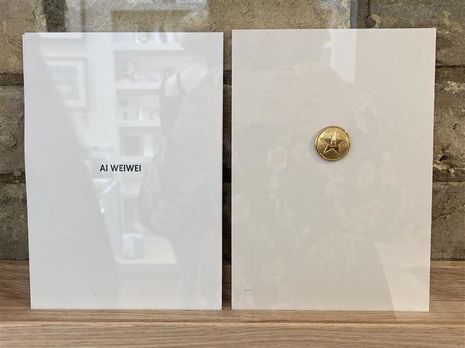

Each set of buttons is affixed to a simple sheet of card beside the name of their artist and propped on a shallow shelf. What lies behind the plane of glass is frustratingly tangible — Jonathan Anderson’s ‘metropolitan’ pigeons, their throats ringed with the better blues and pinks of an oil spill, and Cornelia Parker’s ‘mini theatres of war’, lead toy soldiers stabbed with red thread — that their static setting feels incongruous. Caroline Walker rewards your attention. Her porcelain buttons are painted to resemble tortoiseshells; only squinting do the paler reflections of light reveal their thicker texture. Similarly repurposing the real world, Ai Weiwei worked with Firmin & Sons Ltd, the official button supplier to the British royal family, to reproduce the stars on the uniforms of China’s Liberation Army. Weiwei’s work complicates the button’s substitutive role, recalling the two guards monitoring his secret detention in Beijing: ‘I was instructed not to look at the guards’ faces, so I focused on their buttons.’

“What lies behind the plane of glass is frustratingly tangible, that their static setting seems incongruous”

Other artists expand the button into new territory. Antony Gormley returns to first touch, the ‘rite of passage in childhood when you must become competent to fasten your own clothing.’ His charcoal buttons are edged like a shortcrust pastry, and the fingerprint impressing their surfaces prompts ‘the twin tensions of desire and propriety.’ I am reminded of how in censored films or television programmes, actions like the unfastening of a button stand in for a myriad of human passions.

Edmund de Waal, an alumnus of Trinity Hall College, has written before about the significance of objects in The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance (2010), his family memoir about 264 Japanese netsuke miniatures, the remnants of an extraordinary collection confiscated by the Nazi regime. His buttons, delicate as seashells, are an elegy to Lucie Rie, inscribed with the potter’s name and studio addresses. Even the set’s asymmetric arrangement on the card is considered, seemingly dropped by an open fist yet sewn in place.

“For a moment, the buttons were everything. I was glad there was no glass between us”

Callum Innes also utilises collections, the thumbhole of an old palette informing the shape of his buttons. The electric blue and ‘leaf-like’ buttons of Vicken Parsons are interested, like Gormley, in their own touch: ‘I took a small piece of clay in my hands and pressed it three times using equal pressure with both hands.’ Rana Begum returns to the floor tiles created during a residency in the Philippines to construct her two-tone buttons, their distinctive central pinch moulded from wet clay. Jennifer Lee mixed metallic oxides to create her earthy buttons, their speckles and bands of colour familiar to anyone who has turned over a stone on the beach to discover how the sea has gone to work.

Leaving Kettle’s Yard, autumn was arriving at last in its unhurried way. I retrieved from my bag a knitted blazer, the one I think flits between the wardrobe of a Republican senator’s wife and Kristin Scott Thomas in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994). Fumbling the buttons into their slots, I noticed in a new light the brass-rimmed white whorls like the caps of an Iced Gem, and the union of touch, beauty, and simplicity pleased me. For a moment, the buttons were everything. I was glad there was no glass between us.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026