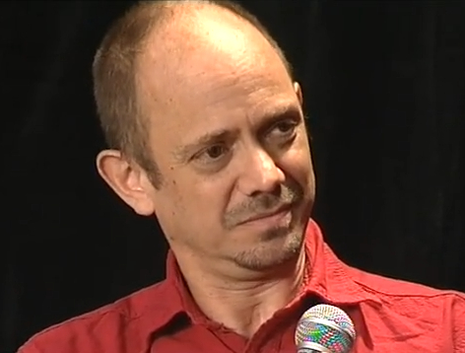

Author Damon Galgut on breaking out of the Eurocentrism of the Booker Prize

His Booker Prize-winning novel The Promise marks a watershed decision to write a book ‘as if South Africa was the centre of the universe’

Sitting down in Waterstones for one of 2021 Booker Prize winner Damon Galgut’s final press events, he seemed determined to emphasise that being awarded this crown of literary fame was simply a “stroke of luck”. Humbly denying the prize as any “recognition of some innate genius” (however tempting this might be), he pointed to how “some terrible books win prizes, and very very fine books are overlooked”.

If so, luck seems to be on Damon’s side, as The Promise’s win is the second time the so-called “Booker Bounce” (when Booker Prize-winning novels experience a dramatic increase in sales) has changed his fortunes. In 2003, the shortlisting of The Good Doctor - his “last throw of the dice” - saved his “shrinking career” at a time when no one within or outside of South Africa was willing to publish his novel, In A Strange Room.

So what sort of book does win?

Despite telling me that The Promise was “the one most likely to” win out of his works, he didn’t know whether that made “it the most deserving”. Even though another novel of his, In A Strange Room is his personal favourite, he explained that it's “not the sort of book that’s likely to win a prize like that.” So what sort of book does win? If it’s not the novels authors love writing the most, is there a danger they’ll resort to abandoning their creative instincts and instead turn their hands to formula-fulfilling books that will tick the judges’ boxes? Those who jump on the anti-Booker bandwagon would say so, blaming it for incentivising writers to churn out modish, politically correct historical fictions. These books may hit the jackpot but not readers’ interests, leading to bookstore shelves lined with the same book in different fonts (well, covers).

The plot of The Promise charts the downfall of white colonial rule in South Africa through a razor-sharp narrator’s account of the crash and burn of one white family. Although some may dismiss it as conforming to a “woke” cliche, the importance of spotlighting these stories of bigotry and oppression should not be diminished. Undoubtedly aware that the justification for their decision will be scrutinised and discussed as much as the book they place in the limelight, it’s clear why the Booker judges prioritise pivotal social commentaries over light reads.

Damon consciously inverts the “diet of European novels” he was raised on

Described by judges as “a spectacular demonstration of how the novel can make us see and think afresh”, The Promise is rooted within South African culture, colloquialisms and references, refusing to accommodate to your average European reader. Damon consciously inverts the “diet of European novels” he was raised on, filled with assumptions of the reader’s comprehension of Eurocentric phrases and references which he couldn’t recognise. Despite previously translating certain “South Africanisms”, The Promise marks a watershed decision to finally write a book “as if South Africa was the centre of the universe” and force readers to “come to us.” His use of the channel between narrator and reader is equally compelling. Sudden shifts into the second person directly implicate the reader in events and refuse any subconscious attempts to create distance between ourselves and the prejudice we become complicit in. Despite the distinctly unique racial hierarchy of apartheid, The Promise’s cross-cultural relevance is crucial. Damon described how “the themes of the book” carry “beyond the shores of southern Africa”, with people in societies with similar hierarchies relating to its power dynamics in ways even he might not understand.

The Booker’s recognition of the novel becomes all the more significant considering how the prize has traditionally been coated in an air of Eurocentrism. In 2013, the decision to consider writers from outside the UK and Commonwealth divided the literary world, partly due to fears that major American authors would dominate the longlist. However, there were also concerns that the inclusivity risked “diluting the identity of the prize”, as one previous judge argued. Considering how insular we can be when deciding the literature we acclaim - with Booker Prize entries still confined to those published in Britain and Ireland - the exposure Waterstones grants The Promise by slapping a big green “Booker Prize winner” sticker on it couldn’t be more crucial. And with this year’s winner, Shehan Karunatilaka’s Seven Moons, concerning the bloodshed that has plagued his home of Sri Lanka for decades, the Booker seems to be continuing the trend of celebrating politically relevant historical fiction. Despite the criticisms, this trend encourages a nation of readers to pick up books that challenge our instinctually inward reading habits.

Whether you see it as a serendipitous stroke of luck for writers or a strategic, politically correct selection, the immense exposure the Booker brings towards such innovatively subversive novels suggests it might not be as superficial as it seems. When it comes to The Promise, at least, it certainly seems to have struck gold.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025