COLOUR: Art, Science and Power exhibition: colour becomes an ‘expressive tool to address discrimination’

From the controversial blue and black Instagram dress to Ancient Greek cups, this exhibition explores our perceptions of colour in ‘exciting and unexpected ways’

“Every colour has its own history.” COLOUR: Art, Science and Power — the latest exhibition at Li Ka Shing Gallery, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology— certainly delivers on this claim. It guides you through varying histories of colour from tracing the importance of yellow in Imperial China, to the science behind colour theory and light. With a range of artefacts; burgeoning technological tools; and contemporary materials, we see the full spectrum of colour from its development to its modern uses. This careful curation is successful in its ability to explore the use of colour through the lenses of art, science and power simultaneously— rather than treating them as entirely separate, allowing us to fully understand how colour affects our perspective of the world.

What does colour mean to you?

Rather than compartmentalising the artworks by place of origin or medium, the exhibition is organised thematically, based on the varying ways in which colour is significant to us. The multi-media dimensions are intertwined throughout, with video and audio material interlaced with more traditional means of presenting colour. The artworks come from a variety of places and time periods: from as close to home as the Cambridge Yarn Collective to as distant as Ancient Egypt. This allows pieces that seem entirely separate to come into dialogue with each other in exciting and unexpected ways.

The viewer’s perception of colour is one of the exhibition’s key preoccupations. Scientific understandings of colour, including Newton’s use of the light prism, are featured in an eclectic display. Social media phenomena were also incorporated, such as the Ishihara colourblind tests; the viral dress from 2015, (causing an inevitable disagreement over whether it was white and gold or blue and black); and the infamous Pink Floyd album. Alongside this muddling of time, which illustrates a near-constant human obsession with colour, we are constantly reminded of where colour comes from. The process of creating colour, including the use and production of inks and pigments made from insects and animals, delves into our relationship with colour in nature.

Moving on from these fundamental ideas, the exhibition makes a point of interrogating our cultural understanding of colour through intersectionality. Importantly, it acknowledges the importance of diversity and decolonisation in developing this understanding. Objects and narratives from across all continents and identities were represented—from ancient Greek crockery to the invention and identity of the various iterations of the pride flag. These pieces all recognise the innovative use of colour to portray feeling, community, and connection.

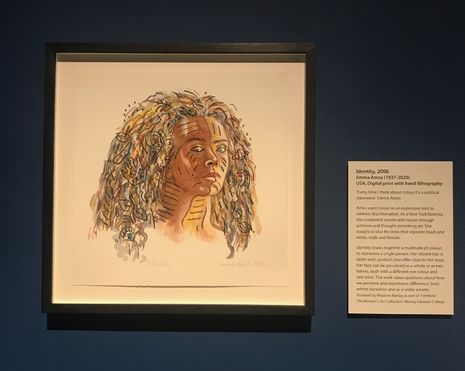

Women’s art was also noticeably present. The exhibition included loaned items from fellow Cambridge museums, the Fitzwilliam and the Women’s Art Collection. One piece, ‘Identity’ by the late Emma Amos, is a digital print with hand lithography (a printing technique that uses a flat surface to work on areas of the print by hand) that explores colour as an “expressive tool to address discrimination”, meditating on colour’s ability to make a political statement. The exhibition has its own go at cleverly curating colour, positioning it beside the aforementioned Greek cup—displayed simply as the ‘Kantharos cup’ (470 BCE)—which depicts two faces with different skin tones facing the opposite direction to each other.

The innovative use of colour to portray feeling, community, and connection

The inclusion of women’s art was not restricted to the twenty-first century. We found particular amusement and resonance with a late eighteenth-century tapestry, fondly signed off “Ann Smith finished this”. Indeed, the exhibition reminds us that women have always made their mark and presence known through colour— reclaiming traditionally ‘female’ crafts like embroidery to present fresh takes on traditional ideas. This particular piece, an untitled 1767 sampler, recreates the temptation scene from the Bible. Refashioning a traditionally feminine craft into a medium for exploring religious ideas, and in such a dangerous intertwining of image and colour, makes for a striking addition to the exhibition.

Other bold statements included Benjamin Zephaniah’s poem, ‘White Comedy’. This poem interrogates the emotional and cultural associations of ‘white’ and ‘black’—perhaps neglected in the rest of the exhibition with its overt focus on the vibrancy of the colour spectrum. It is fair to say that the discussion of race in relation to how we see colour deserves an exhibition all of its own, but it was nonetheless an important idea to incorporate here.

Finally, the viewer is left with one question: what does colour mean to you? When faced with so many perspectives manifesting themselves through the lens of both art and science, it can be difficult to come to a personal conclusion. It’s something that many of us take for granted, especially given the increased availability of coloured pigments, from the paints used for art to the dyes used in our clothes. By bringing ‘COLOUR’ to the forefront of how we experience ‘Art, Science and Power’, the exhibition provides us with a new appreciation for its diverse interpretations, and how they underpin the way we make sense of the world. These joyfully unexpected connections certainly make this exhibition a worthwhile visit.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 Lifestyle / Is three really a crowd? 10 March 2026

Lifestyle / Is three really a crowd? 10 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026