‘Bountiful, intimate and reflective’: The Mays 30 review

As The Mays celebrates its 30th anniversary, Margherita Volpato reviews its latest edition

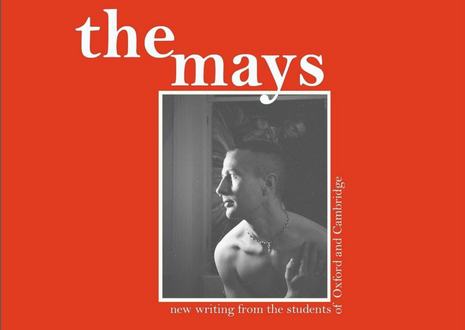

In the right-hand corner of this year’s The Mays, in black-and-white against the striking red cover, sits ‘30th anniversary edition’. These words are both markers of legacy and of perspective. They threw me into reflection. What of those published in past issues, where are they now and how far have they gone? How completely arbitrary yet perfect is it that these voices of the past are connected, via a title and just about one hundred pages of beautifully sturdy paper, with voices of today.

“Olivia Laing’s foreword reminds us that ‘the word anthology means a bunch of flowers’”

Even the forewords written by this year’s editors seem to invite contemplation, and how time shifts and alters perspective. Olivia Laing’s foreword is a summary of her writing life, full of successes and struggles, and she reminds us that ‘the word anthology means a bunch of flowers’. She suggests, therefore, that The Mays is itself a bouquet, one made of writings that capture moments, perspectives and glimpses of eternity despite their acknowledged transience. Kofi Stone urges readers (and writers) to tap into these pockets of time to achieve writing that is truthful and meaningful, whilst Nick Bartlett shows us exactly how to achieve this as he writes: ‘I try to drag crystals of clarity out from within the dark mine of my memory’. All three of these forewords grapple with that struggle to write, to capture and to contain; and yet, they see the value in it, because it is what defines art. The Mays 30, in particular, is defined by this search for and exploration of perspective.

I can’t help but agree with Olivia Laing when she characterised Lindsay Igoe’s ‘The Girls of Camp Arcadia’ and Eliza Browning’s ‘Jeanne D’Arc in the Flatlands’ as ‘Jeffrey Eugenides-inflected’. These prose pieces are stuffed to the brim with nostalgia and it makes them suffocating, entrancing and devastating. Imani Thompson’s ‘To Assassinate a Man’ too literally reeks of nostalgia, as she writes ‘when we were younger we smelt of affordable perfume, sweat and city’. This short story captures both what it is to be stuck in time whilst still managing to hold in its grasp the expansive particularity of memory, and how it relates to objects and people. ‘Huswife’ by Martha French takes this perceptual particularity to a beautiful extreme.

Her long sentences are fractured by short, staccato interruptions but the reading experience is not unwieldy because it reflects thought, it is thought. She moves from person to person, moment to moment, with such fluidity that reading and being become one. Solal Bauer investigates this connection, how words allow things to come into being, with scientific rigour. I felt like his writing transported me. Not to another universe, but to another plane where everything became visible; I need only quote these two sentences to capture my awe: ‘Sharon, the receptionist, is planted at her desk in the lobby. You feel that the building was created by multiplying Sharon into steel and glass’.

“Words here transcend perspective and experience and try to capture something more”

The poetry in this anthology was just as attentive. Tamsyn Chandler’s ‘Schönefeld’ uses forward dashes as its only (bar two expectations) punctuation. They both interrupt and inform the reading experience. I didn’t know, each time, if I should take a breath, or if I should pause, or keep going. Are they meant to separate moments, thoughts, locations or are they placeholders, to show how sentences and lines can be arbitrary limitations of thought? I’m probably reading too much into it, but that’s why I loved it. Tess Solomon’s ‘Preface’ hit me full force with its last stanza: ‘I asked my / sister […] why it didn’t taste more’. It was like a full-circle moment, back to Nick Bartlett’s foreword ‘Taste Beyond the Tongue’. Words here transcend perspective and experience and try to capture something more. How else to describe it but as exquisite?

Mia Griso Dryer’s poem ‘On Days When Matter Matters’ is, exactly because of what others in this anthology explore, cautious of its own fragility; both the self and the poem are aware of their vulnerability to objects, words and time. This self-awareness does not take away any of its impact. Just read these lines: ‘no body is born complete / […] all the parts are never included / you apply pieces of yourself like gel every morning’. Such visual language breaks down the boundary between word and object, between matter and what matters (as the poem’s title suggests).

The Mays itself is aware of this connection, which is why it is rendered all the more special for the photos, paintings, illustrations and sketches it contains. ‘Wiktor in the Wires’, by Niamh McBratney is a visual poem. Colours, angles and shapes bounce off each other and are yet contained within the four walls of the image. Daisy Coombs’ ‘Dream Journal’ is incredible for its perfect balance of serious light-heartedness. I am both amused and concerned with how she controls birds with nonchalance and seemingly finds a puddle indoors. After all, how better to capture the incomprehensibility of dreams than to revel in it? I also love Leong Sui Whey’s ‘Untitled’ photos. They are more traditional in composition, and yet direct and personal in perspective. I can only imagine what memories are held by those chairs, or that stretch of river.

For every complimentary sentence I have written about a piece of this year’s Mays, thousands more could be written about every single other piece contained in it. It was a bountiful, intimate and reflective collection. It is always hard to review such anthologies. Therefore, I’m going to conclude how Olivia Laing began: ‘the word anthology means a bunch of flowers’. This review is even more slim than that. I’ve picked out the flowers that stood out to me and have selfishly displayed them on my windowsill. All you need to do, all The Mays requires of you, is to read it for yourself and pick out your own selection.

You can purchase a copy of The Mays 30 here.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025