Our own 5th Wave: re-reading dystopia during the pandemic

Chloe Bond reflects on the uneasy experience of re-reading Rick Yancey’s ‘The 5th Wave’ series, after a year of living with the pandemic

Contains spoilers for The 5th Wave trilogy.

Content Note: This article contains discussion of graphic physical violence and abortion.

I first encountered The 5th Wave as an overeager preteen, caught up in a slew of post-The Hunger Games releases that promised disconcerting visions of apocalyptic futures, bundled with ‘which-basic-male-love-interest-will-she-choose-this-time?’ romances. Back then, my Instagram handle was still @chloethetribute – which, rather embarrassingly, I only rectified a few months ago. I sped through the first book, unnerved and perplexed by its alarming predictions for a few seconds, and then moved swiftly on to the next made-for-screen YA novel in my TBR pile.

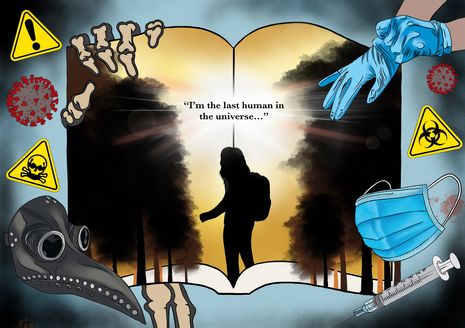

This time it was sitting in my garden, recovering from a mild – but nonetheless nasty – dose of COVID, that I re-entered the fractured, desolate landscape of Yancey’s imagination. Isolated, my street soundless as everyone else went to work, for a brief moment it felt like Cassie Sullivan’s words could be my own: I’m the last human in the universe. With echoes of the last year pulsing inside my head, I devoured the first book just as voraciously the second time around – then consumed its sequels with equal fervour – albeit experiencing an entirely new sense of dread settling into my stomach.

The 1st Wave: Lights Out

The 2nd Wave: Surf’s Up

The 3rd Wave: Pestilence

The 4th Wave: Silencer

- the opening page reads. Pestilence ricocheted off the page, its plosive sounds unbearably loud to my ears. An airborne virus passed onto humans from an animal carrier. Mandatory quarantines. Field hospitals and mass graves hastily assembled to handle its victims. The fictional ‘Red Death’ had bled into my current reality. In this article, Alice Vincent makes the case that the impulse to re-read lies in its potential for allowing us to ‘make amends for our earlier misdemeanours, literary or otherwise’. The 5th Wave, however, is a trilogy which repeatedly resists such an endeavour: at its core are characters faced with the inherent impossibility of correcting their mistakes, propelled relentlessly onwards through a never-ending cycle of guilt and fear of what is coming next.

Most striking of these impossible choices are the moments in which the books’ female protagonists – Cassie and ‘Ringer’ – reckon with the preservation of their humanity. In the first novel, Cassie is cornered in a deserted convenience store by a man she later dubs ‘Crucifix Soldier’ – a wounded survivor whom she shoots after mistaking the cross in his coat for an offensive weapon. The image of his bloodied body, fist curled around the crucifix, is a spectre which Cassie cannot shake; throughout the successive novels she mourns the time before, a time when such actions against another human being were unthinkable. For ‘Ringer’, it is her unexpected pregnancy which makes her loss more acutely felt. The scene in which she contemplates a termination, holding a cap full of antifreeze to her lips and declaring, ‘This is the world they’ve made, where giving life is crueler than taking it away’, in The Last Star lingered with me for far longer than was comfortable.

“The distance between my experiences and those portrayed in Yancey’s fiction had contracted rapidly”

Although, of course, experiencing not nearly the same magnitude of desperation as these girls, I too mourned the naivety of my younger self as I came out the other side of self-isolation. The distance between my experiences and those portrayed in Yancey’s fiction had contracted rapidly, a fact that felt more suffocating than comforting. For the me of 2013, the ‘Others’ were light-years away; for the me of 2021, the ‘Others’ are here, and they’re not aliens at all – they’re my fellow man. Unlike the ‘Silencers’ who hunt Cassie and her friends mercilessly, the anti-vaccination, non-mask wearing minority are anything but quiet. Every day in isolation I watched my Facebook feed fill with posts denying the very disease that was making me feel utterly awful. Even now, several weeks after recovering, there’s a jarring hurt in my muscles simply from taking a short walk to run some errands. Back then, I couldn’t fathom how humanity could be so easily manipulated into turning against itself; I couldn’t grasp what would tear us apart so violently that such inflictions of suffering would become acceptable. Having been through this pandemic, I see the how a little clearer now. ‘Protests’ against COVID regulations demonstrate how easily the things which make us human might be rejected: trust, love, empathy for the vulnerable. When those are lost, we are faced with our own ‘Crucifix Soldier’; desire for self-preservation outweighs civic duty – and herd immunity is shunned for the sake of individual ‘freedom’.

To say I ‘re-read’ this trilogy now feels like a dire understatement. I relived it, my past and current selves moving between the pages intrusively, enacting what Ato Quayson describes as ’interleafing’. Gratingly aware of the reader I was now, and the reader I had been before, my experience was indeed heightened by the duality of re-reading – but, at moments, it intensified to the point of pain rather than pleasure. If the line which separates dystopian fiction from a quasi-dystopian reality is fading at such a dangerous pace, where does that leave the reader – or indeed, the re-reader? Clashing with Vincent, I close by arguing that it leaves us not in a place of comfort or familiarity but instead with the knowledge that such attempts to recapture the reading experience we once had are often a bleak – or nearly impossible – feat.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025

Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025