On Francis Bacon and my sleep paralysis hallucinations

Talia Foster gives a moving account of her experiences with sleep paralysis and how she found comfort in Bacon’s anthropomorphic creatures.

Content Note: This article contains detailed discussions of hallucinations, panic attacks, sleep paralysis and anxiety disorder.

I still remember the first time I experienced sleep paralysis, though it’s been more than a decade since then. It was around ten in the morning, but my bedroom was dark and cool because I liked to keep my curtains pulled tightly when I slept. The only source of light in the room seeped through the bedroom door: a rectangular, yellowed-out halo which slunk in through the crevices of the frame. I knew something was wrong when the sound of static started to fill my ears. The static turned up so loudly that nausea began to kick in. Immediately I found that I couldn’t move. My heart pounded, eyes flickering as I tried to reel in the panic, but the panic became insuppressible as I realised that my limbs were locked in. When my eyes landed on the mirror that stood in front of my bed, something had appeared in its reflection. It was a hunched humanoid figure, grey all over, just standing there motionless, staring at me without eyes. To this day, I still remember what it looked like, the angling of its neck, how real it appeared within the familiar configurations of my room.

“It is because they’re so familiar that I cannot dismiss them as fiction, yet it is because they’re so foreign that I can never surmise their intentions.”

I think that is what’s most unnerving to me about sleep paralysis. It’s not that I can see ghostly figures (I can easily find scarier ones in movies) – it’s that the ghostly figures appear integrated into the scenery of reality. I am not in some rundown motel far from civilisation, nor am I in some clichéd horror-flick forest; fiction warned me about places like that, where the real world is liminal. No, I am in the comfort of my bedroom – and it’s that element of the experience that is the most unsettling. In the years since, I’ve become accustomed to this kind of fear. From cockroaches crawling across my chest, to voices whispering in my ears sentencing me to death, the hallucinations have almost become part of the routine. But my first sleep paralysis experience is still the one that stuck with me the most – and I think it’s because that first encounter took me by surprise, because it undermined the certainty that my room was familiar, that it is a refuge.

To me, then, it’s no wonder that there’s a persistent link between sleep paralysis and anxiety disorders. The relationship is almost too obvious. When I am gripped with anxiety, or experiencing a panic attack, it feels as if the familiar scents, smells, sights of my room have all turned against me. My overloaded senses become so overwhelming that they paralyse, fix me to the spot, in much the same way that sleep paralysis does.

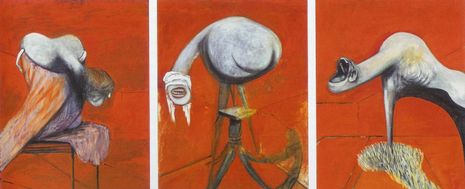

When I first saw Francis Bacon’s “Three studies for figures at the base of a crucifixion”, it was as if my hallucinations and anxiety had converged onto one painting. There have been many representations of sleep paralysis in both literature and art through the ages, from accounts recorded by Ernest Hemingway, to arguably the most recognisable of these representations, Henry Fuseli’s “The Nightmare”. In the search for a depiction most accurate to my experiences, however, I have always found myself drawn back to Bacon’s triptych.

Bacon’s distorted figures, propped onto chairs and stools, conjure up that figure I saw in the mirror as if through some black magic: that greyish creature, animated and hunched, its flexed, organic curvature signifying something of my anxiety. Each pose maximises the monster’s tautness, its tremors, its tense energy. The mouths of these creatures, wide open, gesture with their gape towards the constant discomfort of potential intrusion, of allowing some foreign, unwelcome gaze to peer into the most vulnerable caverns of the body. Just like the figures who appear in my hallucinations, Bacon’s subjects veer towards the human, stopping short at the borders between the familiar and the foreign. It is because they’re so familiar that I cannot dismiss them as fiction, yet it is because they’re so foreign that I can never surmise their intentions.

There is always some strange comfort I find in seeing Bacon’s paintings. The sheer bodiliness of his subjects allow me to grasp firmly onto my experiences, to interrogate my fears in broad daylight rather than give them the opportunity to sneak up on me under the cover of darkness. To see my hallucinations on a painting is to subjugate them, to trap their unpredictable motions onto the nonthreatening surface of a still frame.

Interviews / Lord Leggatt on becoming a Supreme Court Justice21 January 2026

Interviews / Lord Leggatt on becoming a Supreme Court Justice21 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026 News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026

News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026 News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 News / Cambridge psychologist to co-lead study on the impact of social media on adolescent mental health26 January 2026

News / Cambridge psychologist to co-lead study on the impact of social media on adolescent mental health26 January 2026