On Michael Field and the privileging of the female gaze

Anna Trowby reflects on how Michael Field changed her perspective of Victorian literature.

Upon approaching the second year of my undergraduate English degree, I initially dreaded the thought of studying Victorian literature. Being told repeatedly by literary critics and lovers alike about the lusciousness and inventiveness of this era’s writing did nothing to temper my frustration for Victorian authors. I found the works of these esteemed artists to be shallow and empty, caught up in the artificial glory of ornate writing. I also struggled to emotionally relate to any of these writers, since any sentiments bubbling beneath the surface of their writing were often congealed in complex sentences and rigid forms. A governing principle of much literature during this era was Walter Pater’s now famous aphorism of ‘art for art’s sake’ - art that exists simply for beauty, which in turn makes us appreciate our own humanity by allowing us access to ideas that transgress time and decay. But as far as I was concerned, this process also involved transgressing cognitive understanding and accessibility, and I fought to make sense of Victorian lyrics.

“Upon approaching the second year of my undergraduate English degree, I initially dreaded the thought of studying Victorian literature.”

Fortunately, my hardline position against Victorian literature has since evolved. This change of heart occurred after I first came across the work of Michael Field, a poet who has since opened my eyes to the true radicalism and artistry that can be found in this era’s poetry. Upon studying literature from the 1800s onwards, the name ‘Michael Field’ popped up repeatedly, and, naturally, I was curious to find out more, especially as it never seemed to be clear who this writer was. You can imagine my shock when I discovered that ‘Michael Field’ was not a real person at all, but a pseudonym for an aunt-niece writing duo by the names of Katharine Harris Bradley and Edith Emma Cooper. While the use of male pseudonyms for female writers is commonplace throughout history, it is extremely unusual for writers to use a false identity for collaborative work. (Cooper and Bradley are the only authors I know of to have used a pseudonym in this way.) The pseudonym also covered up the scandalous nature of their relationship, as Cooper and Bradley were also a lesbian couple trying to live their life in relative privacy. Their identity was later outed by poet Robert Browning, who served as a mentor to the duo, and they became the subject of salacious gossip and rumours in London literary circles, but they continued to live together and collaborate on numerous volumes of poetry.

“Field succeeds not only in occupying space in a male-dominated tradition, but also in reigniting my fascination for Victorian era poetry.”

What is so remarkable about ‘Michael Field’ is not only the circumstances of their relationship, but most importantly their proto-feminist poetry, which privileges the female perspective in male-centric writing traditions. Their work has unfortunately declined in popularity since its peak in the late 1800s, but thanks to the work of women’s studies scholars who have helped to revive the writings of numerous forgotten women, Michael Field is enjoying a renaissance of critical interest. While much of their writing deals with the female condition and perspective, I was particularly struck by their collection, Sight and Song. Based on the paintings of Renaissance masters, Sight and Song contains a series of ekphrases meant to ‘translate into verse what the lines and colours of certain chosen pictures sing in themselves’. Field also sets out to show what the paintings ‘objectively incarnate’, putting aside their own subjective responses to the painting, but as we shall see, the understanding of objectivity in each painting also involves an engagement with the interior consciousness of their subjects.

Over the course of the volume, Field takes male-centered art, often featuring nude female figures, and reinvents them in verse form. In doing so, Field compels the reader to adopt the female gaze, and see the artwork from their perspective as opposed to the male artist. The exploration of female subjectivity may seem out of place for a collection that aspires towards objectivity, but perhaps Field was searching for a different type of impartiality, one that sought to rebalance the unequal scales between the male artists and their female subjects. Their poems offer a life to the character that art, in its permanent stillness, cannot. In ‘Spring’, Field notes Venus’ sadness, and the movement of the other characters away from the central protagonist; the poem ends with the other figures leaving the goddess in solitude to get on with their lives. This movement, which cannot be captured by painting, gives added depth and emotionality to the scene, and humanises Venus, who is equally transformed by this extra-dimensionality. Female solitude is also explored in ‘Birth of Venus’, inspired by Botticelli’s iconic painting, which presents her ‘new-born beauty’ before delving into her subjectivity. Field comments on the ‘tearful shadow in her eyes’, and ‘candour far too lone to speak’, noticing how Venus’ defiant pose hides a deeply insecure and isolated woman.

“For these reasons, I will always be grateful to Michael Field”

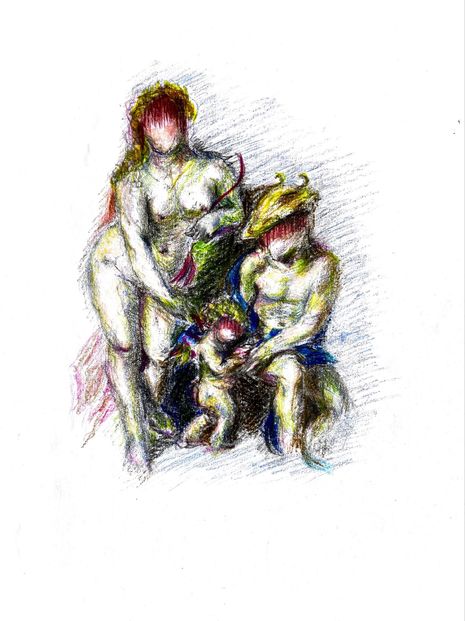

Prefaced with an epigraph from the Romantic poet Keats, ‘I see and sing, by mine own eyes inspired’, Sight and Song is firmly rooted in the aestheticist tradition, which often makes use of florid and detailed descriptions. Field’s immersion in this tradition initially seems at odds with their privileging of the female perspective, given that aesthetic lyrics are liable to depicting surface level beauty with no further meaning. This trope becomes more problematic when applied to portrayals of women as decorative objects rather than sentient beings, commodifying the female form by reducing them to their bodies. However, Field recenters the female gaze, restraining from commenting on the women’s physical forms to instead focus on their innate subjectivity. In ‘Venus, Mercury, and Cupid’, Field adopts the classical painting by Correggio, which features a sexualised portrayal of the goddess Venus tending to a young Cupid, and instead refocuses the image as a celebration of motherhood and tenderness.

Field succeeds not only in occupying space in a male-dominated tradition, but also in reigniting my fascination for Victorian era poetry. Their poetry has made me realise that there is more to aestheticist literature than pretty images and turgid sentence structures. Rather, Victorian writers were exploring concepts of sex and gender in exciting and progressive ways even in the constraints of their society. My discovery of Field has also exposed me to more Victorian era lesbian writers, namely Radclyffe Hall and Elsa Gidlow, who are also enjoying a renewal of interest in their work and lives. For these reasons, I will always be grateful to Michael Field for saving my faith in Victorian literature and teaching me that radical artistry exists in the most surprising places. Along with reclaiming the significance of female subjectivity in objective forms, Field reclaims their humanity and sentience, giving female subjects space and freedom in predominately male literary traditions. Read their work, if you dare.

Sources:https://www.lennyletter.com/story/michael-field-lesbian-writing-duo-victorian-era

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026