Between the Iron Curtain and Vaccines: Gabriel García Márquez in the Eastern Bloc

Introducing Gabriel García Márquez’s travels through the Eastern Bloc in the 1950s, Karolina Filova suggests that his reports offer an intriguing survey of the ways countries can emerge from crisis and isolation.

Over a decade before publishing A Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez travelled to Europe as a reporter for the Colombian journal El Espectador. He remained on the continent between 1955 and 1957, a period ridden with paradoxes and transformations. While Nikita Khrushchev’s De-Stalinisation reforms and foreign-policy rhetoric of ‘peaceful coexistence’ promised a transformation of life under Soviet influence, the brutal handling of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution spoke volumes to the opposite effect. To see for himself the realities of life under such contradictory conditions, García Márquez embarked upon a number of visits across the countries of the Eastern Bloc.

The book written about his travels, published in 1978, appears to document a single three-month voyage through the Eastern Bloc; in fact it compiles García Márquez’s reports from a number of separate journeys: a secret train trip to Czechoslovakia and Poland in 1955, a visit to Leipzig and East Berlin in 1957, and a journey to Moscow as a foreign delegate to the World Festival of Youth, followed by Hungary, which had been previously closed to foreigners. Through these destinations, García Márquez offers a brief insight into a wide range of experiences – a look both unavoidably alien and deeply insightful, engaging in personal conversations wherever possible.

“What can be surprising is the clear plurality with which García Márquez describes the countries he visits”

Though it may not be immediately apparent, there is perhaps a parallel to be drawn between the travels of García Márquez and the current pandemic. Not only are García Márquez’s difficulties with travelling reminiscent of the increasing complications connected with international travel today (testing, quarantine, passenger location forms, and potentially vaccine passports), but the broader context of paradox recalls current times as well: despite living through a major health crisis, we make an effort to conduct ordinary life at a distance. While experiencing the spread of a tangible disease, we are being affected just as much by a mental health crisis. We can picture García Márquez travelling between several quarantining nations, all with varying severity of symptoms and hopes of escaping their terribly paradoxical reality.

García Márquez brings an intriguing perspective to his reports of the Eastern Bloc: his own leftist worldview prevents him from being a dismissive critic of all aspects of life under socialism, but he also manages to convey with striking clarity the disappointment and shock of first experiencing the low living standards and various forms of disillusionment. Upon his arrival in East Germany, he comments on the shock of seeing a population so poorly dressed, noting the trauma evident in their demeanour. He remarks disappointedly on the disparity between Soviet space-programs and the empty stomachs of its citizens.

If nothing else, García Márquez offers a valuable lesson – or a chance for self-reflection – on how we react when exposed to a reality confronting our ideals or expectations. Perhaps another parallel emerges here with today’s health crisis, which has revealed a profusion of issues that seemed well-hidden in what we considered normality. In the face of a reality that doesn’t line up with our expectations, should we give up our ideals completely, revise them, or (as García Márquez seems to do) observe and try to understand just how they part ways with reality?

“All the different narratives read like possible scenarios for a post-pandemic world”

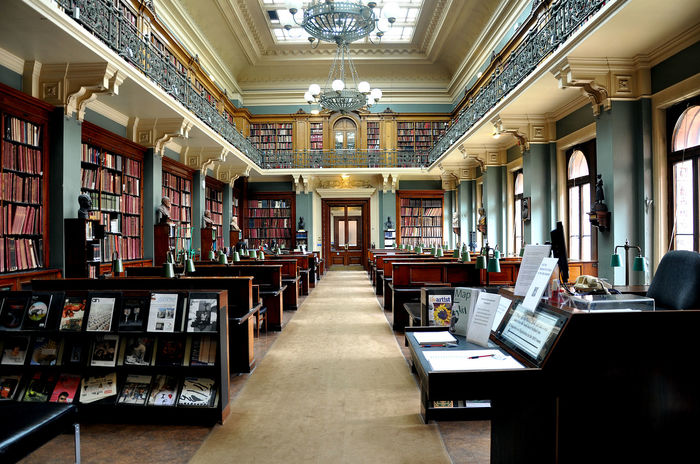

To a reader most familiar with history-lesson generalisations, what can be surprising is the clear plurality with which García Márquez describes the countries he visits. In Poland, he remarks that everybody is reading all the time, speaking French whenever possible; Czechoslovakia is at first glance indistinguishable from a Western country, experiencing a cultural revival. By contrast, in Berlin he observes a yearning for unification, unsatiated by the prosperity of its citizens. García Márquez likens Moscow to the largest village in the world, full of people touchingly desperate to make friends. In Hungary, he notes that people are afraid of speaking to him, and that the revolt continues in anonymous inscriptions on the walls of public restrooms.

The experiences of countries in the Eastern Bloc, García Márquez shows, were far from assimilable into a single overarching narrative. Strikingly, though the specifics of the situation of the Eastern Bloc are very distant to the issues we are currently facing, all the different narratives read like possible scenarios for a post-pandemic world. We can only guess at which path we might follow as we emerge from the health crisis – one of cultural revival, population-wide trauma, dissidence only to a certain degree, an impulse to foster interpersonal connections, or any combination of these at once. García Márquez offers a snapshot of a range of countries in very specific historical conditions, observed from an alien but not disinterested perspective, and within it provides an insightful exploration of just how broad the possibilities are when emerging from a crisis.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025