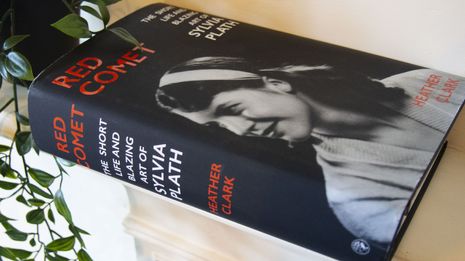

Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath, by Heather Clark

Lindsay Taylor review the latest – not-inconsiderable – biography of this most considerable of poetry figures, whose time at Cambridge is often overlooked in favour of the more grotesque

Considering all the exceptional men and women who have graced Cambridge University’s halls – from philosophers to movie stars – Sylvia Plath, an American poet, who published just two collections and one novel during her short life, can seem dwarfed in comparison. Though her name sparks recognition in most, it’s usually in connection to her graphic suicide at the age of 30. Like Marilyn Monroe or Amy Winehouse, Plath and her art are often overshadowed by the sensational nature of her passing, transforming her into a metonym for melodrama and female hysteria.

Within Newnham College, which Plath attended in the late 50s on a Fulbright Scholarship, her name is heard in higher frequency, though not necessarily with more familiarity or affection. To many young women there, the name “Plath” still remains fettered to death and depression. Even within the graduate house Whitstead, where Plath lived during her time in Cambridge and where I currently reside, there is the tendency to blame unexplained noises on “Sylvie’s ghost” and her former room is universally acknowledged to have “bad vibes.”

“Like Marilyn Monroe or Amy Winehouse, Plath and her art are often overshadowed by the sensational nature of her passing, transforming her into a metonym for melodrama and female hysteria”

In an exhaustive new biography, Red Comet, author Heather Clark sets out to disentangle the real-life Plath from her lugubrious ghost. Clark starts her story before Sylvia’s birth, tracing her origins back to her father’s birth in Germany and his subsequent emigration to the United States. Aided by the journals that Plath kept since girlhood, Clark painstakingly continues to follow Plath’s personal and artistic development from childhood onward, with each lengthy chapter corresponding to a year or two of Plath’s life. The amount of research and attention to minute detail is astounding – in an early chapter, Clark even recounts the contents of a home-made birthday card a young Sylvia sent to her mother. Though the biography is engrossing overall, at over 1,000 pages in length, this tome is not for the faint of heart.

By the time Clark reaches Plath’s years at Cambridge, the reader has become intimately familiar with the bright, bold, and endearingly fallible Plath. She resembles many Cambridge students: intelligent and ambitious and overwhelmed at the thought of failure. It’s hard not to see similarities between myself and the young Plath, especially as someone who shares her suburban New England upbringing. Though I would never presume to share her talent, I can relate to her struggle to heat the drafty rooms at Whitstead, as well as her feelings of displacement in a foreign country. Based on Clark’s description, the Newnham of Plath’s experience was vastly different from the college in 2020. She did not find a diverse community of support at Newnham as I have, but struggled to make friends among her British peers, who found her embarrassingly American.

While I can vouch for the fact that Newnham is more welcoming to Americans today, based on my peers’ reactions, it seems the student body hasn’t warmed much towards Plath in the intervening years. Perhaps it’s for the simple reason that – unlike many other Newnham alumna – Plath doesn’t make an easy feminist icon. Though Plath chafed under misogynist conventions of her era and was acutely aware of its double standards, Clark makes a point of reminding the reader that she was not a champion of “women’s lib.” With her classic good looks and suburban-housewife aesthetic, if anything, Plath is associated with a sort of white, middle-class feminism, at which Newnham students are likely to scoff.

Though I too began Red Comet with this preconception, Clark brings a Sylvia Plath to life who is too vivid and complex to be limited to her broadest strokes. I had conceived of Plath as a caricature, a view as reductive as failing to see past the circumstances of her death. It brings to mind one of Plath’s earliest published poems, Mad Girl’s Love Song, which is punctuated with the refrain “I think I made you up inside my head.” The poem makes a fitting companion to the biography as it typifies the equal forces of rage and sorrow which accompanied Plath’s short life and are keenly felt by all young women who continue to read her poetry today. I believed I’d outgrown Plath, but after spending 1,000 pages with her, I can confirm that the poet I thought I knew was one I had made up inside my head.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025