Nations, novels and new beginnings

In her third column of the series, Angharad Williams reads Azar Nafisi’s memoir and examines the power of reading to reclaim a home

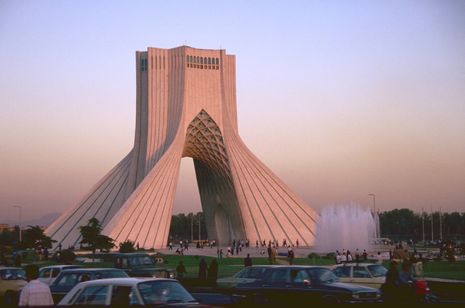

While it is the most common association, the idea of home is not restricted to a house and its occupants. For most of us, home will also refer more broadly to a town, city, or country where we feel a sense of belonging. While we never have complete control over what happens in our homes, this is especially true in these larger spaces. This understanding is brilliantly captured in Azar Nafisi’s autobiographical novel Reading Lolita in Tehran, which explores the author’s return to a home she no longer recognizes and the ways in which she attempts to reclaim a sense of belonging.

“The club is not so much an escape from an unhappy home, but a form of resistance to it”

Nafisi is an American-Iranian author and academic, and the book begins as she returns to Iran after several years of studying abroad. At the time of her return the Iranian Revolution was underway, dramatically transforming the political and social structures of the country. Nafisi’s homecoming is not the joyous event that homecomings are typically depicted as, but is rather characterised by a deep sense of foreboding. Starting from the moment of her entrance to the country, when her books are damaged by airport security, Nafisi stresses the ways in which her values come to be at odds with those of the country. Nafisi explores the question of what it is to feel at home; her experience highlights that physical presence alone is not always enough. Rather, the feeling of home for Nafisi seems to be a type of collective unity, in which different individuals, and ways of life can be accepted.

Despite the fact that Nafisi focuses on a sense of national belonging, the private home remains absolutely central. It is here that Nafisi feels the sense of having lost a place she once treasured most intensely. She explores this primarily through the predicament of women like herself, whose lives became increasingly restricted after the revolution. She focuses in particular on the freedoms afforded to different generations of Iranian women in her family. She is shocked to consider the fact that, while she had more opportunities than her mother, those afforded to her daughter are similar to those of her grandmother, notably the marriage age in the country is brought down from eighteen to nine. These freedoms affect the position of women in public spaces; an example of this occurs when Nafisi is expelled from her university teaching post for refusing to wear the hijab. However, it is the restrictions which affect the private home that unsettle Nafisi the most, as it means she is unable to find any place in which she feels entirely comfortable.

Nafisi though is not entirely miserable while living in Iran, the novel itself is centred around one of the things which brings her joy – a book club. The book club is established by Nafisi, held in her home, and she invites all her best students to join. The structure of the book club forms the structure of the novel, a clear indication of just how important the group was to Nafisi. However, the club is not so much an escape from an unhappy home, but a form of resistance to it. Although not overtly political, the novels the women read for the book club facilitate complex discussions of topics which would – in the context - have been considered taboo. Furthermore, these open and deeply empathetic conversations are in direct opposition to the oppressive conditions in which they are living. Ultimately though, home is something permanent, and the book club merely temporary. By the close of the novel Nafisi has moved abroad, her life too difficult to bear even with that sanctuary.

Home then is not always a personal and private space: for most it also refers to a broader region. The two are experienced very differently, with the latter often beyond our immediate control. The work of Azar Nafisi points to the fact that the two are tied together in creating a sense of belonging, and when this sense is lost it cannot always be regained, even through acts of resistance.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026