Aliens, hedgehogs and horror: Earthlings review

Mj Lewis reviews Sayaka Murata’s latest book, reflecting on how language can both alienate and inform and how sometimes, otherworldly beings are the least of our worries

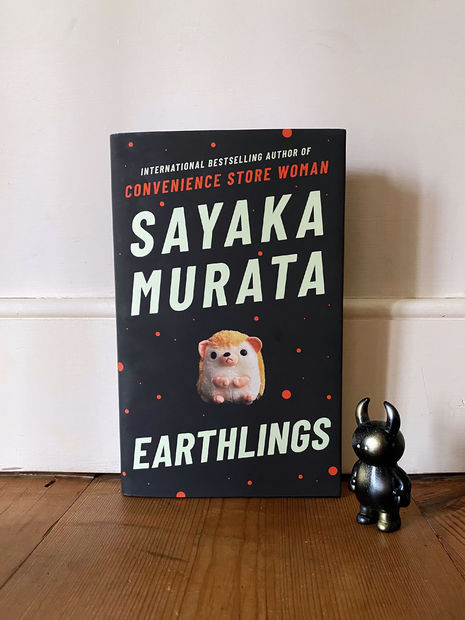

The cover of Sayaka Murata’s latest publication in English bears a cute, if slightly melancholy, stuffed hedgehog. Despite its appearance, this is not light reading. In fact, I think it’s as far from light reading as anything could possibly be. It opens innocently enough, with 11-year old Natsuki accompanying her parents and sister to her grandparents’ house in rural Nagano. The aforementioned stuffed hedgehog, it turns out, is named Piyyut, and is her magical guide from Planet Popinpobopia. He’s given her powers, and she has a mission to protect the Earth. Still with me? I know I said this wasn’t light reading, but I’m getting there, I promise.

“In Earthlings, by contrast, the simple and unaffected writing style can only be described as chilling”

Earthlings is split into two distinct halves, with the first following Natsuki over the course of her early adolescence and the second skipping ahead to her mid-30s. As a child, she feels alienated from her immediate family but finds herself drawn to her cousin Yuu, who confesses to her that he himself is an alien. Delivered in Murata’s signature deadpan tone, these childish fantasies are so sincere that they’re almost angelic. But predictably, as the story progresses there are hints of the darker themes to come: at one point, Natsuki catches a live grasshopper and, unable to open the screen door to release it outside, feeds it to a spider instead.

As the events of the narrative become more and more bewildering, the deadpan tone starts to have a very different effect. In her previous novel, international bestseller Convenience Store Woman, it served almost as comic relief, with protagonist Keiko left constantly perplexed by things that the majority of society see as totally normal. In Earthlings, by contrast, the simple and unaffected writing style can only be described as chilling. Murata relays intimate details of alienation, sexual abuse, and murder in the same voice that someone else might use to describe their trip to the supermarket.

It’s this conscious eschewing of flowery language combined with the book’s relative brevity (it clocks in at just over 200 pages) that make it so strangely readable. I say strangely because it deals with such disquieting subject matters that it’s hard to say in good faith that it was an ‘enjoyable’ read, but it’s certainly masterfully constructed and very deliberate in its subversion of our expectations of Japanese society, and indeed Japanese literature.

“there are no grey areas here, and each twist and turn heightens a creeping nausea”

Though hardly a page goes by without a mention of magic or aliens, Earthlings has a very different feel to the magical realism of writers like Haruki Murakami because we as readers are under no illusions about the actuality of the situation: there are no grey areas here, and each twist and turn heightens a creeping nausea, just like that which Natsuki’s sister experiences on the car ride into the mountains in the opening scene. The final chapter is nothing short of deranged, a thrilling crescendo that leaves the aftermath of the chaos largely up to the reader to muse on.

Though certainly stirring overall, Earthlings feels slightly underdeveloped, and somewhat lacking in momentum in parts. Where Convenience Store Woman reads as a nuanced and convincing criticism of the suffocating pressures of modern society, this beats the reader over the head with the alien/alienation metaphor like a baseball bat, with constant references to ‘the Factory’, ‘receptacles’ and ‘tools’. Perhaps this was meant to further estrange the reader and the protagonist, but it interferes with the flow of the narrative and becomes repetitive and tedious after a while.

In terms of pacing, too, once it becomes clear that there will be no fairytale ‘resolution’ between Natsuki and Yuu in their adulthood, the story meanders back and forth between Tokyo and Nagano before dropping a cliff in the last few pages. This doesn’t detract from the impact of the ending, but feels a little unnecessary at times.

Earthlings is as bewildering as it is compelling, a rollercoaster exploration of the violence inherent to social cohesion. Though these days the term ‘horror’ is more commonly associated with excessive gore or elements of the supernatural, it strikes me that Earthlings has a lot in common with definitive works of horror like Dracula and Frankenstein, in that the apparent ‘other’, be that vampire, simulacrum, or apparent alien, is merely a metaphor for something infinitely more terrifying: human nature.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025