Safe as Houses?

Adam Dumbleton looks at the place of the literary home in our post-lockdown world

The significance of home has rarely been more evident than during the crisis of recent months. Each of us has, to some extent, strengthened existing associations with home as a place of security and comfort, whilst also forging new understandings of the home as a space of work, productivity, and communication. For most, otium and negotium have rarely occupied the same contested space in quite this way.

Yet, just as our most cutting-edge innovations in remote working have brought us circuitously back to a locally-focussed mode of living, we are reminded that for some, such an existence has long been familiar. Our simultaneously being cloistered and yet thinking intensely about our position in the outside world is perhaps most familiar as the experience of writers. Though some consciously eschew a public role whilst others wade deliberately into controversy, the fundamental experience of writing a poem, a novel, or new research alone in one’s room has changed little over the centuries in which other occupations have become unrecognisable.

“For most, otium and negotium have rarely occupied the same contested space in quite this way.”

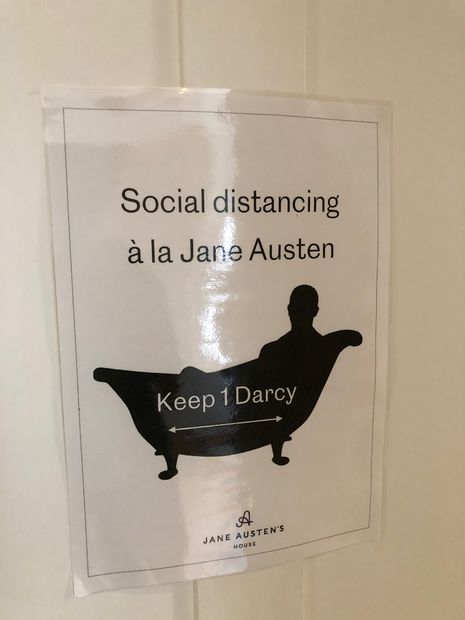

If we should like to historically ground our new experience of the writer’s home-bound life — and make our present seem a little less alien — we can do so at the many writers’ house museums which dot the nation’s countryside. Inside Jane Austen’s house in Chawton, Hampshire, what is believed to be the author’s original writing table is wedged into the parlour between the kettle on the fire and teacups on the table. Breakfast and business jostle for the limited space. Who, now, cannot relate to such a scene? Those who visit in these times realise simply that laptop and latte have replaced ink and paper.

And now is most certainly the time to visit. It is no secret that our national hibernation has thrown the already precarious finances of the arts and cultural sectors into an emergency like never before. But behind these headline generalisations, the crisis has exposed the gulf in funding priority which divides the major national institutions from those of equal importance but lesser stature.

Writers’ houses stand as an eloquent symbol for the plight facing many such less visible establishments. They are mostly small, independent, and overwhelmingly reliant on volunteer input. They lack the voice which enables larger institutions to lobby for funding and attention. The trustees of Austen’s house at Chawton made clear in their appeal for emergency funds that, like many places, they faced the genuine prospect of closure before the end of the year without income from ticket sales. In many cases, the threat lingers: very large donations from a small group of committed supporters might recover losses from the start of the peak visitor season, but by the winter months, fixed costs remain and visitor numbers dwindle again. This model is clearly not sustainable.

Yet for all this, houses like Austen’s represent all that is vital and cherished in the landscape of our national heritage. They are widely dispersed: from Wordsworth’s Dove Cottage in Cumbria to Hardy’s several homes near Dorchester, they are accessible to people up and down the country. They are historically diverse: as Milton’s cottage in Chalfont St Giles allows us to stand briefly in the chaotic death throes of the Republic and the early days of the Restoration, so too standing outside Virginia Woolf’s sometime front doors across London brings us to the seat of modern revolutions of a more literary nature. The houses speak histories we might otherwise overlook: from the Brontës’ parsonage in windswept Haworth, the extent of the effort expended and cultural shock incurred in travelling to London in order to engage with disagreeable publishers becomes apparent.

Such moments of realisation can spark newfound admiration in first-time visitors, and renewed appreciation of writers’ tangible human experiences in those more used to poring over words on the page. And that’s before the engagement potential of bespoke furniture and wallpaper, architectural design and landscape gardening, recipe books and period clothing are considered. Few attractions can appeal to such varied interests. Many locations run innovative and original engagement programs for families and schools. If we are serious about contextualising the past in its proper place rather than displacing it to be stuffed and mounted in a gallery, and serious about doing it in a way which can encourage new demographics to engage with our heritage sector, what else can tick so many boxes?

There is something about the innately historicising mindset of literature which renders these places particularly apt monuments to our cultural past. We are literalising Henry James’ “visitable past.” We are turning ourselves ghost-Wordsworths, visiting and revisiting to reflect on time, landscape, change, and our place amongst these processes.

Yet precisely this awareness of why the places are valuable also reminds us that nothing is immune to the forces of change. Many of us have grown up and been educated in a period and place of peaceful stability, taking for granted the continued existence of sites, institutions, and historical narratives we value. The present moment is the time to realise that we are each of us directly responsible for their survival. Without such an acknowledgement, the tiny, the eccentric, the niche and the unique independent institutions which lend our collective cultural heritage such vitality will silently disappear, taking with them stories and experiences which are recoverable nowhere else. So let’s take action while we still can, and join the encouraging numbers who have been returning since sites began to reopen. Vote with your feet. Stop at the donation box instead of walking past. Volunteer one morning per month. I’ll see you there.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / Corpus FemSoc no longer named after man6 February 2026

News / Corpus FemSoc no longer named after man6 February 2026 News / Lucy Cav students go on rent strike over hot water issues6 February 2026

News / Lucy Cav students go on rent strike over hot water issues6 February 2026