Fitz Favourites: finding perspective with Ethel Sands

In this week’s column, Damian Walsh finds new ways to look at Ethel Sands’ Still Life with a View over a Cemetery

It’s that time of year again. With Week Five successfully navigated (we did it everyone!), thoughts turn towards the end of term, any inclination to work falling away like the leaves from the Jesus Green trees. Winter is creeping up on us, you’ve probably (like me) inexplicably caught a second round of freshers’ flu, and the rest of term can feel simply like a matter of survival. Bunker down in your room, finish off the last few essays and then head back home where life begins again. In all this rush, it’s easy to forget the here and now – and the wonderful art we have close by. Venture out of your cosy, Lemsip-stocked room and head to the Fitz: art is self-care par excellence.

Brightly saturated – some would even call it gaudy – it’s a painting that makes no apologies

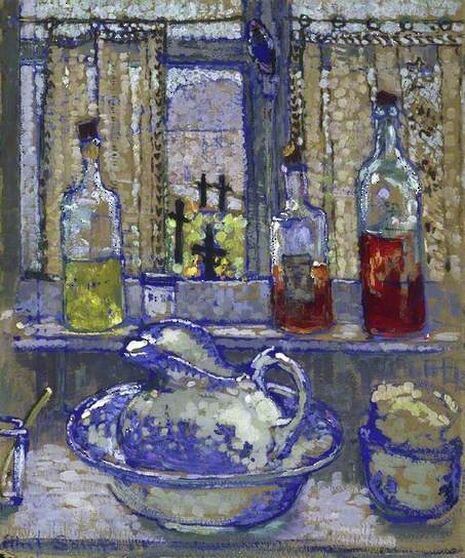

I’ve used this column so far to look at overlooked artworks, but Ethel Sands’ Still Life with a View over a Cemetery is difficult to pass by. Brightly saturated – some would even call it gaudy – it’s a painting that makes no apologies, commandeering your attention towards its domestic objects. Three bottles of various lurid shades stand on a bathroom shelf. In front, a washbasin and jug, various containers: familiar objects of 1920s life. Behind them, past the curtains, through the window, at the furthest point of the canvas are four jet-black crosses: the cemetery of the title. The blue china shines with an almost electric brightness; you can spot it from across the room, if you’re looking out for it. But the crosses assert themselves more gently, and all the more poignantly for it. To misuse Roland Barthes’ famous photographic term, they work as the punctum of this image: they prick you, or pierce you, when you notice them. Is this painting another example of the memento mori tradition? Or a more historical reminder of the cost of the then-recent First World War? We’re given no definite answers.

Sands’ painting is one of layers: I find placing yourself at different distances from it can help to bring out more from its surface. Stand as close as you can to the canvas (without a security guard shouting at you). Look at the light refracted through the right-hand bottle: beginning as disparate strokes of red, yellow, blue, beige – as you start to move back these shapes arrange themselves into a transparent, glass whole. When you come forward again, they break apart. This painting can be mesmerising. You might look like an idiot walking backwards and forwards in front of it, but you’ll be having a lot more fun than most visitors pretending to understand the art.

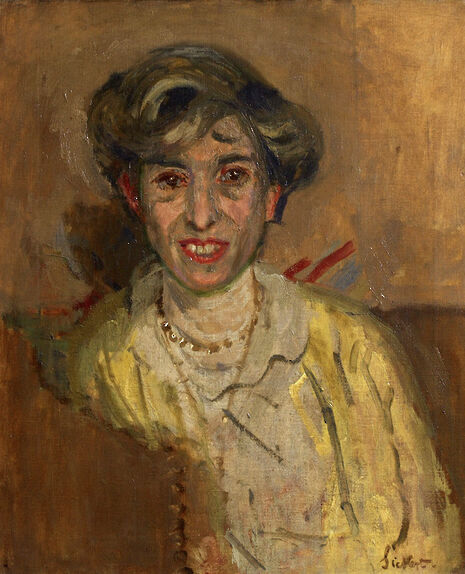

This painting tells a story of being overlooked in a different sense, too. Firstly, it’s one of the few works of art in the Fitz by a woman; the room it’s in has only one other painting by a female artist. That would probably come as no surprise to Sands herself, who faced sexism throughout her life. Though she was close friends and artistically associated with Walter Sickert, whose paintings fill this room, Sands was excluded from his Camden Town Group of Post-Impressionists by default, as a woman. Female artists in 1920s London were generally seen as unusual, praised for their eccentric ‘individuality’ rather than the quality of their art. Sands is still known primarily as a ‘socialite’ rather than a painter. She did have her successes, though, becoming a founding member of the London Group, a collection of experimental artists challenging the Royal Academy’s conservative outlook. She was also friends with the likes of Henry James and Virginia Woolf. The latter’s short story ‘The Lady in the Looking Glass’ was even inspired by watching Sands.

Sands also spent most of her life living in Paris, London or Oxford with her lover, Anna Hope Hudson. Not that you’d learn this in most writing about her. You’ll find the couple referred to merely as ‘friends’ or, euphemistically, ‘longtime companions’. Ethel Sands is yet another example of queer and female perspectives being sidelined in the history of art. While the dazzling colours of her canvas here might be hard to overlook, her contributions to the art world – and even the basic facts of her daily life – have fared differently. She brings luminosity to her domestic scenes, but her work was regarded as little more than a pastime by her male contemporaries at the time.

These assumptions about the way we produce and present art are, thankfully, starting to change. The University’s The Rising Tide exhibitions celebrating 150 years since Girton, the first college for women, was founded are a very welcome example of this. Why not visit the UL’s exhibition on your way back from the Fitz?

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025