Time for Markheim

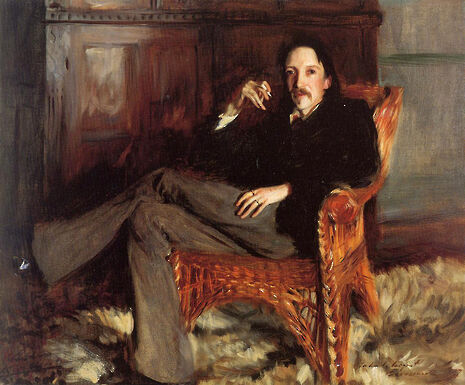

James Inkster discusses Robert Louis Stevenson’s lesser-known tale of gore and guilt.

Half-awake on a belated train, I searched through my Complete Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, looking for my favourite of his short-stories: Markheim. I turned the pages, passed the usual titles, and couldn’t find it. I shook my head. I scanned the contents page. Where is it? Where is it? And then, at last, I found it. For half a minute, though, it was like receiving a Complete Shakespeare and Hamlet being absent. Something was wrong, and my sleepy, sun-stricken self was utterly confused. When I finally found it, the universe had returned to its usual order, but my resolution had already been made: I would write about Markheim, so that fewer people would overlook it when perusing the contents page.

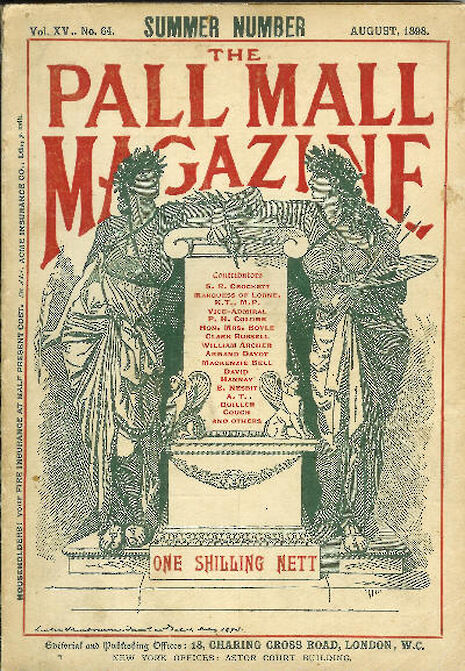

The tale, which recounts the murder of an antique-dealer and the perperator’s crisis of conscience, was originally meant for The Pall Mall Gazette in 1854. In the end, it was published in Unwin’s Christmas Annual of 1855. Even then, it seems, the tale was going missing, and turning up where – and when – it wasn’t expected. When you search for articles regarding Markheim, 1966 is usually the latest accessible essay; the story’s story ends there. This is a shame, because it’s one of Stevenson’s best. Famous for The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr Hyde, or for Treasure Island and Kidnapped, some of his shorter work goes unnoticed. It hides in the shadows, like Markheim as a thief.

It’s about time that Markheim received the attention it deserves. Time, Stevenson tells us, 'had [a] score of small voices' in the antique shop, and Time is key to understanding this story. Markheim, having killed the antique-dealer, is oppressed by the tickings of the clocks and watches. Each second marks another moment in his life of guilt; each minute is one minute closer to being found out. Long before Eliot and Woolf, Stevenson settles upon Time as a nominal key-note: ‘“Time was that when the brains were out,” he thought; and the first word struck into his mind. Time, now that the deed was accomplished – time, which had stayed close for the victim, had become instant and momentous for the slayer.’ Amidst these ‘voices’, Markheim begins to panic and Stevenson tracks his descent into regret and fear. What if someone should knock? What if he should be caught? He senses the gallows moving towards him through the street, second by second, and this twenty-minute tale is fraught with suspense.

Where Wilde has two paintings, and Doctor Jekyll has two selves, Markheim offers itself as a ‘hand conscience’, the short-story as a kind of pocket mirror

Markheim’s present moral course is loathsome to him. He has arrived at the shop under the pretence of buying a lady a Christmas gift, and when the dealer hands him a ‘mirror’, Markheim is repulsed: ‘“I ask you,” said Markheim, “for a Christmas present, and you give me this – this damned reminder of years and sins and follies – this hand conscience!”’ His deictic ‘this...this...this’ points a jabbing finger at the mirror, and his shame and anger grow. After the deed, he is wracked by conscience, surrounded by Time and Mirrors – the ‘years and sins’ in the glass, the reminders of his moral-ugliness and his imminent arrest. And yet, as he waits, paralysed by his own ill-doing, a curious figure appears in the shop… He – God? the devil? – explains that all sin leads to ‘Death’, and the chain of cause and effect rattles out before Markheim’s mind. He’s trapped in his life of sin: he’s made his choices. But then, this apparition – who looks a little like Markheim, one more mirror, the ‘hand-conscience’ given a personified form – offers him a way out. He tells Markheim to kill the woman who he knows is about to enter the shop, and then Markheim will be free to make his escape… Or he can hand himself over.

Translating the female voice

Whether Markheim remains bound to his evil destiny is for you to read. And when you do, watch as Stevenson’s delicate style patterns the work like an intricate sketch; watch as Stevenson offers us mirrors and doubles, as he – like Oscar Wilde in The Picture of Dorian Grey – exposes the duplicity of the Victorian culture. Where Wilde has two paintings, and Doctor Jekyll has two selves, Markheim offers itself as a ‘hand conscience’, the short-story as a kind of pocket mirror. In the glass, in the tale, Markheim sees himself in a way the Nineteenth-Century often failed to: the story exposes the awkward truths of trading stolen goods, murdering innocent people, and, as the antique-dealer’s death implies, being selective with connections to the past. Time, both as history and as a finite commodity we spend, is everything, and Stevenson shapes it into a powerful metaphor:

‘We should rather cling, cling to what little we can get, like a man at a cliff’s edge. Every second is a cliff, if you think upon it – a cliff a mile high – high enough, if we fall, to dash us out of every feature of humanity.’

This story, with its 1,200 seconds, will keep you clinging to the cliffs, and then it will be summer, and your time will be more expansive.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025