Anthea Hamilton: Projects review

Exploring Anthea Hamilton’s installation and curation, Eli Hayes gives us a glimpse into this fascinating new exhibition at Kettle’s Yard

Anthea Hamilton describes the sensation of moving through the house at Kettle’s Yard as one of “discovery”, a “relentless moment after moment of finding things beautiful.” Each time I’ve visited the Ede’s former home, I am struck, like Hamilton, at how frequently I am overcome with an almost childish joy and fascination. As you walk from room to room, your pace inside is matched by the changing light outdoors. A sculpture may have a golden hue in one moment but cast a grey shadow the next. Every visit brings with it a new object of interest; where once I spent an hour fixated on the many pebbles, I was, on this occasion, drawn to the mirrors and reflections that are placed almost theatrically throughout, offering the opportunity to insert yourself into the collection.

Hamilton’s Projects in the House feels like an extension of this sensation. You might even visit the house and fail to realise her interventions are interventions, that they do not belong. But there are certain moments in which the matter-out-of-place makes itself known; a shocking colour or a repeated pattern sparks a conversation, between visitors, between works, between observer and artist.

“What is most, perhaps paradoxically, exciting about Hamilton’s Projects is just how easily the house absorbs them.”

Maria Zahle’s Caput (2018) is the most successful here. The combination of the texture of the linen, the rigidity of the structure, and the glinting of the fool’s gold around the shape’s edges creates a piece that is utterly captivating. It is almost onomatopoeic in form: its mangled anatomy hinting at a dramatic entrance into space. In Latin, caput means ‘head.’ In German, however, it implies something broken, imperfectly put together. And so it sits, playfully, opposite Gaudier-Brzeska’s Head, as if the two were literally in conversation; one a disfigured, comical effigy of the other. In front of the window, catching the light, the two characters mirror the discussions occurring at the table next to them.

Hamilton’s first engagement with Kettle’s Yard was back in 2016, when she reimagined the then-closed house through its archived resources and works from herself and collaborators. Pursuing the same themes of “extraction” and “distillation,” Projects is intended not only to refine particular moments of excitement within the existing collection, but to platform new conversations between otherwise exterior artists. Hence, the works she has interwoven through the house are not all her own, some artists she showcases have been previous collaborators and others are new additions to her dialogue. The conversation is thus extended: opened up to the audience, thrown back through the history of the collection, and cast forward to the potentiality of new partnerships.

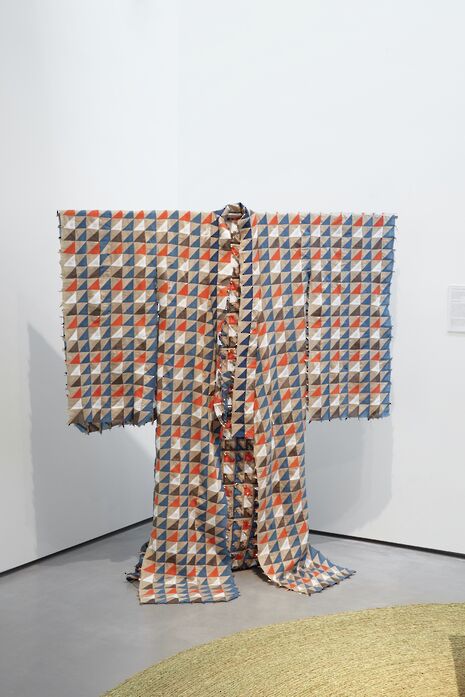

This synergy is embodied most by Hamilton’s own Christopher Wood Kimono (2016). Part of her previous exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield, this kimono, which belongs to a larger ongoing series, has an instant visual relationship to the work it sits beside. Christopher Wood’s Self Portrait (1927), a familiar face to any regular visitors, is hung in such a way that the most striking and memorable feature is his patterned jumper. It makes sense, then, that this is the iconography Hamilton elected to centre in her intertextual intervention. An intervention, which, in its own right is imposing and impressive; she stitched together the hand-cut and dyed triangles herself, a labour of love she suggests was inspired by the care Ede showed for his home.

There are parts of Hamilton’s set design which are less successful. The Nicholas Byrne hanging in the downstairs extension is a subtle change; difficult to notice even with exhibition guide in-hand. Other works are fascinating in a more peculiar way. Laëtitia Badaut Haussman’s Sans titre (Secession), which consumes the ordinary neutrality of the white sofa, plays with an intriguing narrative (so long as you take time to notice the postcard on the shelf beside it), but does so not by reflecting sunlight or inserting colour. Instead, the large, mysterious lump feels ominous; a successful intervention but out of sync with its counterparts.

What is most, perhaps paradoxically, exciting about Hamilton’s Projects is just how easily the house absorbs them. I went to the house in order to find the treasure she had buried, using the printed guide as a map. Others – families, friends, tourists – had not gone with such an agenda. And so, as I meandered the floorboards, and watched as people took their own photographs of Ede and Hamilton’s collaboration, it struck me that a larger parallel was occurring. Visitors of the house were being invited, consciously or not, to do as Hamilton had, and create their own interventions.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026