Point blank: in defence of the blank canvas

Although often the butt of derisory jokes concerning modern art, Jade Cuttle thinks we shouldn’t be so quick to write ‘invisible’ art off as lazy or pretentious.

In the gallery of art that doesn’t visibly exist, the hooks are hanging onto a heavy weight, but as brushstrokes are replaced by blankness, this mass is mostly in the mind. I am not always entirely convinced about this self-conscious snubbing of the aesthetic, as it’s hard to be sure when such a large selection has been but a hoax. But I am, however, very intrigued.

I’d actually describe with defiance Invisible: Art about the Unseen, 1957-2012 at the Hayward Gallery (2012), as the best exhibition you’ll never see. Whilst some masterpieces included a piece of paper at which an artist stared for 1,000 hours over a period of five years, and a plinth upon which Warhol briefly stood before stepping off, other pieces were more solemn. For instance, an exhibition by Teresa Margolles entailed her collecting water that had been used to wash the bodies of murder victims in Mexico City’s morgue before placing it in a humidifier, clinging grimly to the skin of the spectator.

“Modern art is meaningless”: there’s nothing that grates on me more

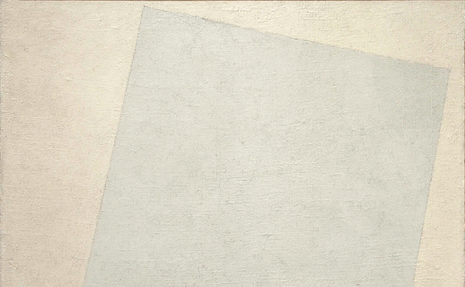

Taking this a step further, there’s Robert Ryman’s Sans Titre (1974) that is basically a plain, white canvas. But what’s fascinating is the shift to the spectator projecting their own ideas onto a plain surface as a means of making art. The piece also takes an interest in physicality, exploring what Paul Klee called ‘the painting’s anatomy’: dissecting the medium of painting until you’re simply left with its skeletal remains, canvas and brushstroke. We’re peeling back the flesh of aesthetics, and when you cut these canvases they bleed potentiality, a powerful yet invisible presence.

Nam June Paik’s Zen For Film (Fluxfilm No. 1) (1964) is another fascinatingly empty piece, reinterpreted in the moving image form. It is video art stripped down to its core basics: a loop of clear, unexposed film leader is passed through the projector, showing nothing but the flicker and fumble of scratches dug in by dust over the years.

As we wait and wait for the film to start – the slim few at the Pompidou who stay to see it through – we soon realise there’s neither start nor end. We are left with pure materiality and a lingering sense of longing that leads us into the land of contemplation, and again, imagination – also into mumbled pardons as people hesitantly pass in front of the screen. It’s a brilliant spectacle of shadows, where the spectator (and their creative faculties) is the leading star.

Admittedly I wrote my 4th year Cambridge dissertation on the politics of interpretation, defending the value of contemporary art in the pecking order of art history. And so naturally - after the solitary confinement dissertation slog, living off scraps of tinned sardines from the safety of my desk – I now feel very strongly about loosening the shackles of subordination, ever so slightly, and arguing that imagination can be trusted to pioneer a more central role in perception.

“Modern art is meaningless”: there’s nothing that grates on me more, and Piero Manzoni’s Merda D’artista (1961), the tinned-shit, is the fall-back example people like to use. There’s never been so much scandal packed into such a tiny space, a metal tin measuring 4.8 by 6.5 centimetres (1.9 by 2.5 inches). Initially, Manzoni‘s project was to produce invisible paintings. But this series takes the idea of invisibility one (slightly grotesque) step further: 90 tins, each concealing 30 grams (one ounce) of his own excrement, purchased by weight at the going price of gold. Admittedly, it’s gross. But the aim was to shake the spectator’s confidence in their conception of art, and undoubtedly cause a stir.

Each artwork here shows an attempt to escape from the frame of expectation, casting aside the shackles of convention and its codes in the ultimate spectacle of innovation. Rule-breaking means mind-bending, and nothing screams creative genius more than bursting beyond the banks of convention in order to poke around in the untouched territory of the imagination - rather than just imitation, skilfully accurate as this may be. If art is about creativity and imagination, it doesn’t seem too outrageous to propose a work where this skill is demanded of the people interacting with it, surely? And a blank piece of paper, after all, is the best fodder for a hungry mind

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Arts / A beginner’s guide to Ancient Greek tragedy16 December 2025

Arts / A beginner’s guide to Ancient Greek tragedy16 December 2025